Published in 2020 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2020 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Smith, Devlin.

Title: Coping with fake news and disinformation / Devlin Smith.

Description: New York: Rosen Publishing, 2020. | Series: Coping | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019009353| ISBN 9781725341203 (library bound) | ISBN 9781725341197 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Media literacyJuvenile literature. | Fake newsJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC P96.M4 .S64 2019 | DDC 070.4/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019009353

Manufactured in the United States of America

On the cover: Thanks to connected devices, we now have constant access to information. Accuracy and validity arent guaranteed so its important to develop tools to judge that information.

Some of the images in this book illustrate individuals who are models. The depictions do not imply actual situations or events.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

W hen Apple released iOS 12 in September 2018, the update included the new feature Screen Time. It provides users with reports on the amount of time they spend on their phones and what they are doing, like using apps or going online. Digital Wellbeing was introduced for Android devices in November 2018 and provides similar information to users about how they interact with their phones.

According to data reported by Nielsen in a July 2018 study, Americans spent an average of three hours and forty-eight minutes a day on digital media in the first quarter of 2018, with most of that time spent using apps to go online with their smartphones. Released by the Canadian Internet Registration Authority (CIRA) in March 2018, Canadas Internet Factbook 2018 revealed that 74 percent of Canadians spend at least three to four hours a day online; 14 percent spend more than eight hours a day online.

Online we shop, connect with family and friends, watch videos, listen to music, do research, and get news. The information and news we find online, though, may not be accurate. Stories from long-established media brands, like national magazines and local newspapers, blogs, message boards, and social media channels, find their ways into our feeds, presenting information that could be true, inaccurate, false, or fabricated.

With features like iOS Screen Time and Android Digital Wellbeing, smartphone users can better understand their digital habits, including the amount of time they spend online.

Judging the quality of the information and news we find online can be a challenge, as Christian Picciolini, a reformed neo-Nazi and peace advocate, described for the CNN special report Spreading Hate: The Dark Side of the Internet. Theres so much misinformation out there, its tough to distinguish whats real, whats fake, whats propaganda, whats parody, and its confusing for young people who are searching for an answer, he said in the special.

If it aligns with our beliefs and confirms our biases, we may spread fake news and misinformation across our social networks. Our shares can lead to more shares, and that bad information will continue to spread. Even if our followers are limited to close family and friends, what we share can have an influence. For those with larger followings, their posts can have even more of an impact. Deema Al Asaid, a social media influencer, shared the concerns she has about what she posts in the 2017 documentary Follow Me:

The more followers I have, the more responsibility I feel about what I share on social media because its such a huge responsibility, so I try to take it seriously, and I hope that all the people who are actually influencers and have people following them, they take this really seriously, because the power of social media, or saying anything on social media, is crazy.

Whether your social network includes millions or just hundreds of followers, you can take action to limit the spread of fake news and disinformation. You can explore the positive and negative impacts news media can have, learn how to judge the validity of the information you find online, and discover resources to help you develop better news judgment.

CHAPTER ONE

A Free Press

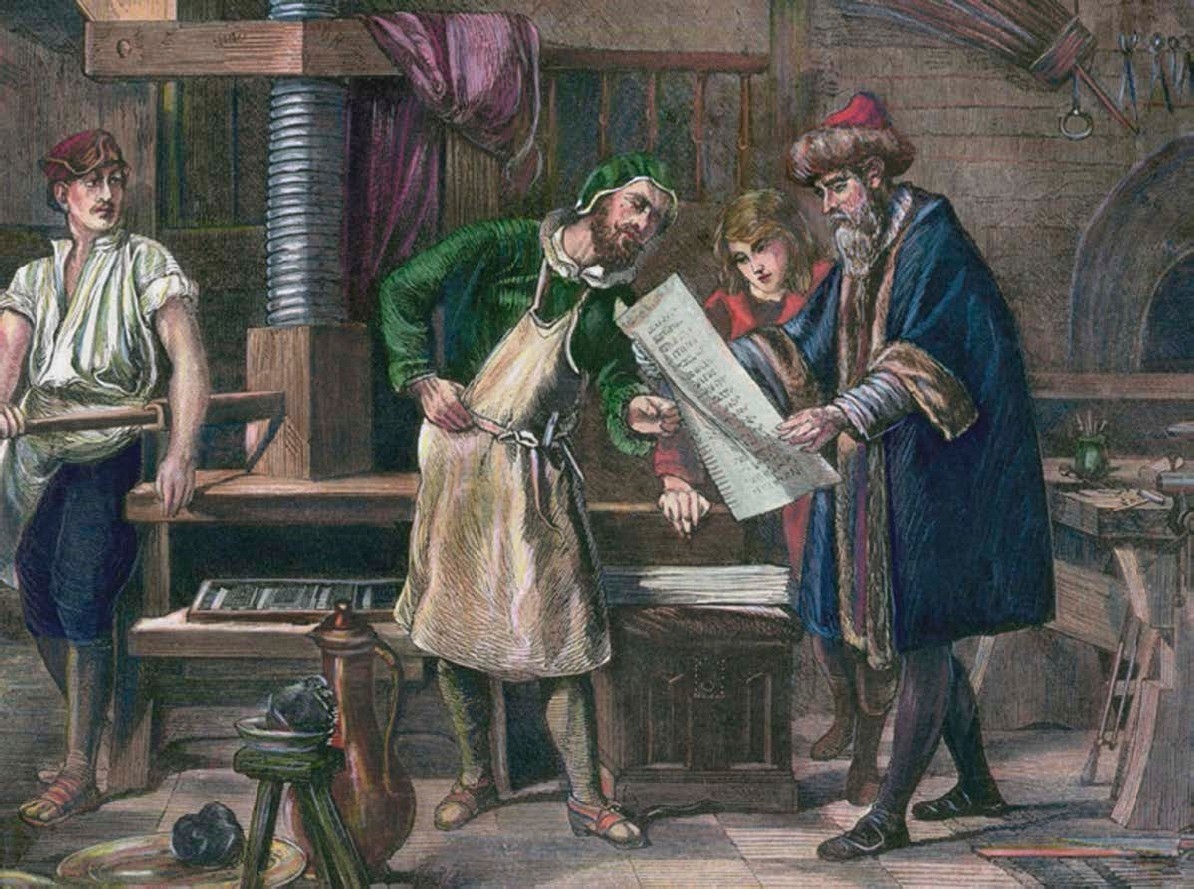

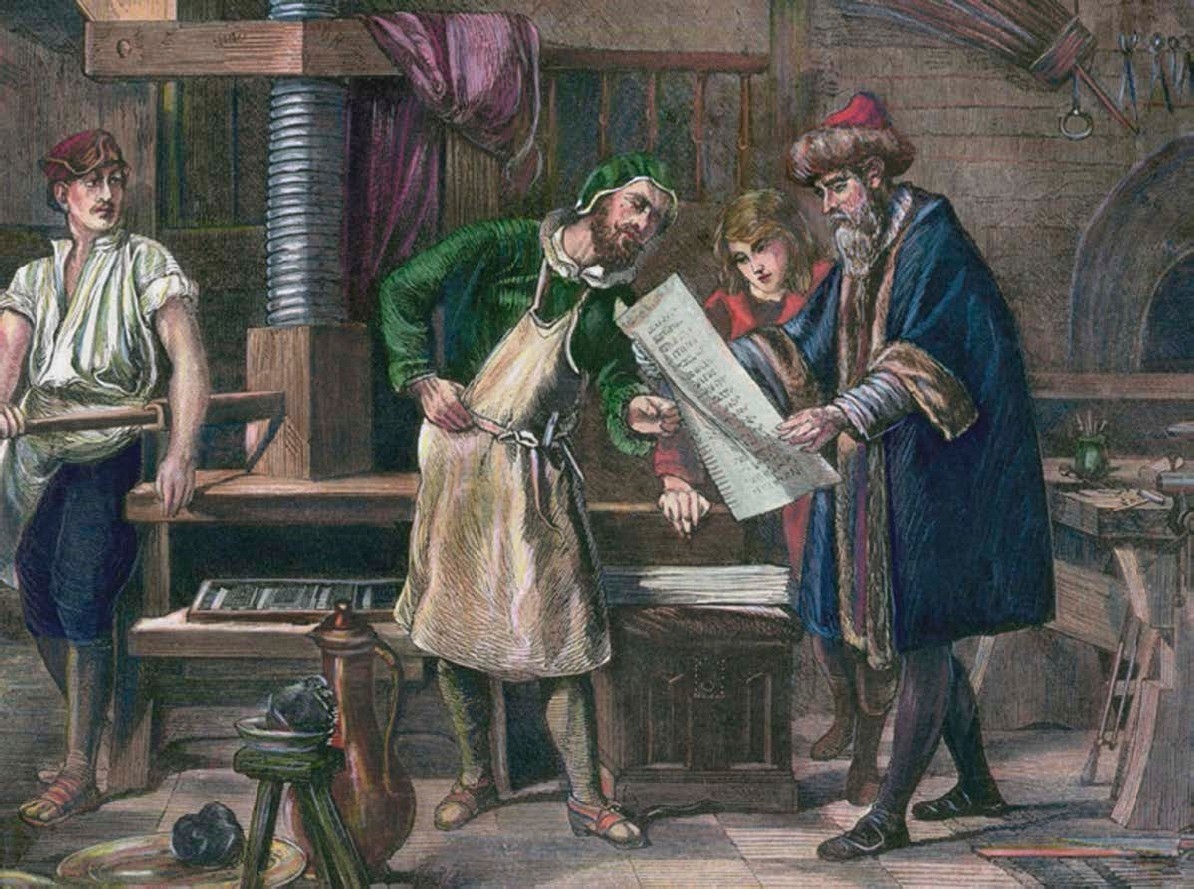

J ohannes Gutenberg changed the world. Prior to Gutenbergs invention of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century, the reproduction of books, pamphlets, and other media was most often done by hand. Books were in short supply, and with few books, few people were able to read. At the time of the printing presss invention, just 30 percent of Europeans were literate, according to data shared by Tatiana Schlossberg in an article that appeared on McSweeneys Internet Tendency on February 7, 2011.

The automation provided by Gutenbergs printing press led to the release of more books, pamphlets, and other media. With words and information more readily available, more people were able to learn to read. Three centuries after the printing presss invention, the US Constitution was signed, and 60 percent of the new countrys free adult population was literate, according to data shared by Schlossberg. In 2017, the UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) Institute for Statistics (UIS) reported that 99 percent of adults in Europe and North America were literate; the global adult literacy rate was 86 percent.

Johannes Gutenbergs invention of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century led to vast increases in literacy and in the production of books, pamphlets, and other print media.

Gutenbergs invention laid the groundwork for generations of technologies that would continue to improve access to information, including typewriters, copy machines, and computers. The printing press also enabled the development of journalistic print media later to include radio, television, and the internetthat collectively became known as the press.

Controlling the Press

When technologies emerge, governments often debate what regulations should be enacted, determining who can use the new technology, how the new technology can be used, and when the new technology can be used. Cars, for example, are heavily regulated.

All drivers need to be licensed. To get your drivers license, you must reach a minimum age, complete training, and pass tests. Once you have your license, you must obey the laws of the road and renew your license every few years. Speed limits are set to restrict how fast you can drive your car. Drivers and passengers must wear seatbelts. Infants and small children must ride in car seats or in booster seats. Car owners are also responsible for maintaining their vehicles for road safety.

Public safety informs regulations placed on cars. Throughout history, though, governments have sought to regulate the press in order to control information that is spread, including limiting or eliminating the spread of information that is critical of the government.

In the seventeenth century, one way the press in the United Kingdomand later the British colonies in North Americawas regulated was through licensing. In accordance with the Licensing Act, before any book or pamphlet could be printed, it had to first be registered with the Stationers Company, a government-approved guild of printers. (The Stationers Company is still in existence today, with over nine hundred members who represent press organizations, as well as paper, print, publishing, and office products companies.) By requiring registration, the law was, as detailed in Karen Nippss 2014 article in the

Next page