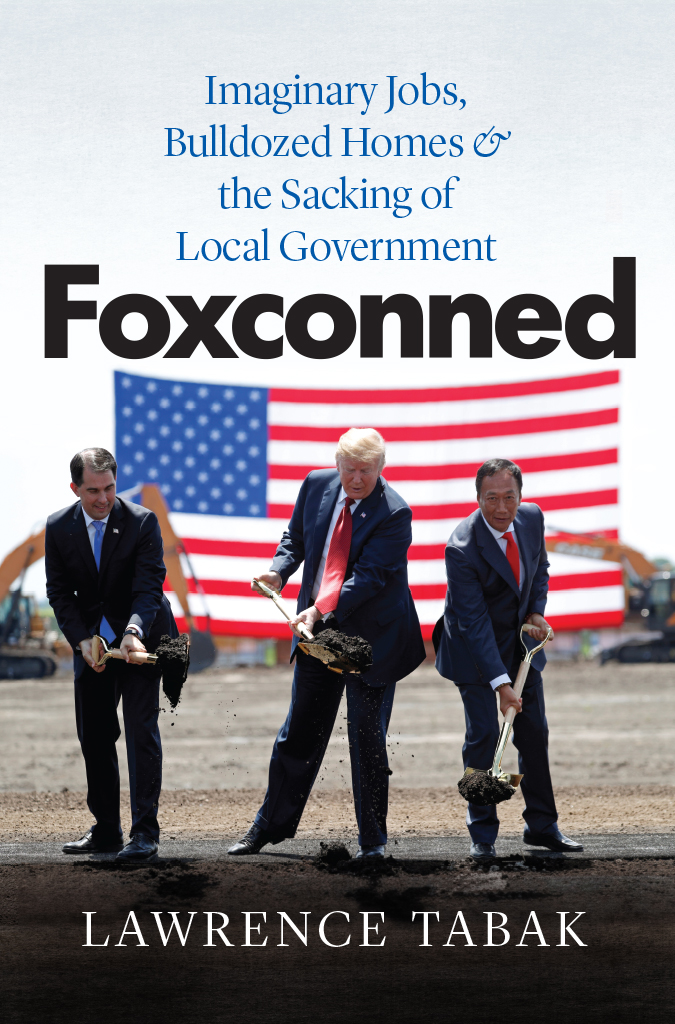

Foxconned

Foxconned

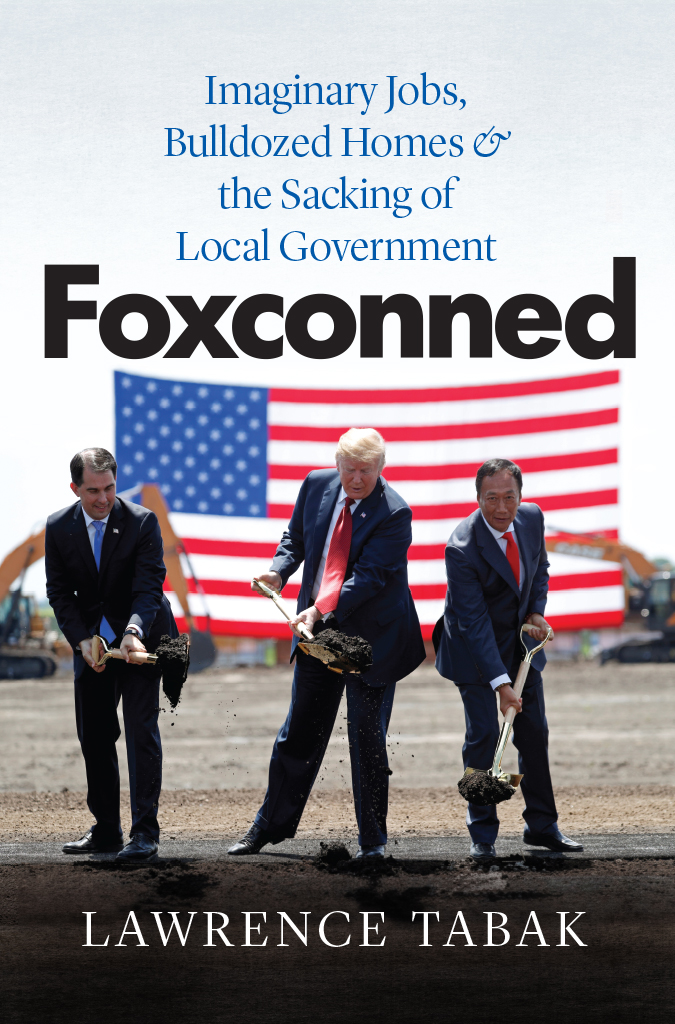

Imaginary Jobs, Bulldozed Homes & the Sacking of Local Government

Lawrence Tabak

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2021 by Lawrence Tabak

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2021

Printed in the United States of America

30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-74065-2 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-74079-9 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226740799.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tabak, Lawrence, author.

Title: Foxconned : imaginary jobs, bulldozed homes, and the sacking of local government / Lawrence Tabak.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021016959 | ISBN 9780226740652 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226740799 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Foxconn International Holdings Ltd. | Industrial development projectsWisconsinRacine County. | Economic development projectsWisconsin. | Industrial promotionWisconsin. | Economic development projectsPolitical aspectsWisconsin. | Economic development projectsSocial aspectsWisconsin. | Tax increment financingWisconsin.

Classification: LCC HC 107. W 62 R 338 2021 | DDC 338.7/62138109775dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021016959

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For my beloved econ-major son, Zach

Contents

When I was growing up in Dubuque, Iowa, my best friends father had an appliance store on Main Street. Its windows were crammed with wonders: blurry color TVs, clock radios with glow-in-the-dark radium dials, hi-fi consoles. Before leaving for college, I purchased a little stereo there from an up-and-coming Japanese company called Panasonic.

Back then, blue-collar workers were firmly part of the middle class, and a hardworking high school graduate could support a family by working the line at the John Deere Dubuque Works or at the Dubuque Packing Plant, home to the famous Fleur De Lis hams. Diversity was pretty much limited to religionProtestants and Catholicsalthough a handful of African American families lived on a little triangle of land on Hill Street. The rest of the city was restricted either by covenants or by common practice. We had one public high school, and the wrestling star Jordan Smith was the only Black student in the class ahead of mine; there were no Black students in my class. The Hispanic population, as I recall, was the foreign exchange student from Venezuela.

But even during my childhood this world was already in transition. First Plaza 20, with Iowas first Kmart, opened on the west side of town, followed by an indoor shopping mall. Downtowns largest department store, Rosheks, moved to the mall, and the mom-and-pop stores began to close. The city elders (they were all men back then) despaired at the ruination of their downtown and snatched up $7 million in available federal urban renewal funds. They razed empty buildings, moved the clock tower onto a pedestal, and turned Main Street into a pedestrian mall. All it lacked was pedestrians.

Then came the industrial calamities. In the late 1970s, a line worker at the Dubuque Pack made $25,000, the equivalent of $87,000 in 2020 dollars. Employment at the factory peaked at 3,500. But these high wages and associated benefits, along with an outmoded factory floor, made the plant noncompetitive against newer facilities elsewhere that were hiring lower-paid, often immigrant labor. There were layoffs and salary cuts, and in 1982 the plant shut down, pushing the towns unemployment rate over 17 percent. I wouldnt be the only Dubuquer moving away for goodthe citys population peaked in 1980.

But like cities across the country, Dubuques urban renewal efforts had given the city its first experience in taking commercial development into its own hands. Up until the late 1960s and into the 1970s it would never have occurred to most city officials to get into the business of managing retail or industrial development. Today, long after federal urban development funds have dried up, it is rare to find a town or city that isnt actively involved in promoting development and using tax advantages, infrastructure investments, land grants, and municipal debt to attract businesses.

In the 1990s, I landed an assignment to do a story for Ingrams, Kansas Citys business-friendly city magazine, on a proposed $90 million ($160 million in 2020 dollars) expansion of the convention center, Bartle Hall. Not only was the expansion promised to reinvigorate flagging convention traffic; it also was promoted as a major cog in revitalizing a moribund downtown.

After a deep dive into the topic, I submitted a story that detailed how the investment was destined to disappointboth in terms of ancillary downtown development and in the balance sheet for the facility itself. Something of a countrywide civic arms race to expand convention space was under way; overbuilding and the unlikelihood of sufficient expansion in convention business would lead to financial jeopardy for most of these facilities. I also found plenty of support for the notion that the economic impact studies that endorsed the building craze were deeply flawed and perhaps even cynical. One of my sad discoveries was that cities were encouraged to throw good money after bad: consultants would explain shortfalls by pointing to lack of exhibit hall space or hotel rooms and claim that for a city to make good on its current investment, it would have to spring for bigger halls and subsidized hotelsoften at considerable civic expense.

The editor of Ingrams read my submission with horror and immediately canceled the assignment. But I continued to work on the story and eventually found a home for it in the Atlantic Monthly. The story was then republished in a number of venues, including the Sacramento Bee and the Charlotte Observer, papers in two cities contemplating convention center expansion.

In July 2017 I was thinking back on that story while watching President Trump and Wisconsins governor Scott Walker on the news. They were at the White House, announcing a major industrial development for Wisconsin, where I live. A Taiwan-based company, Foxconn, had committed to building one of the largest factory complexes in the United States, promising to spend some $10 billion and to hire 13,000 workers. As I read about the frantic interstate bidding that had gone on for that factory and the grand projections of economic benefits, I couldnt help but think of the convention center arms race. Wisconsin offered Foxconn up to $3 billion in incentives to build the factory there, a figure that would expand to $4.5 billion when combined with infrastructure expenses incurred by utilities and the local municipalities. This amounted to $346,000 per job, an absurd figure. And it wasnt only the size of the subsidiesthe announcement at the White House signaled a new level of politicization for economic development.

In early August 2017, I pitched Belt Magazine

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).