For my family, with gratitude

ALSO BY KIDADA E. WILLIAMS

They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I

Charleston Syllabus (with Keisha N. Blain and Chad Williams)

CONTENTS

Question: Now, tell us whether the Ku-Klux raided on you. Answer: Well, they came to my house about midnightsome time in March When I saw death coming I got out Abraham Brumfield, York County, South Carolina, 1872

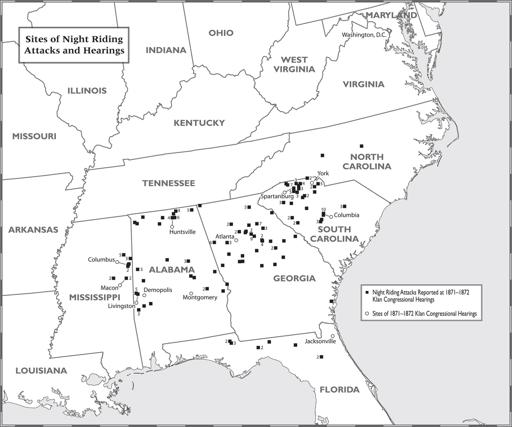

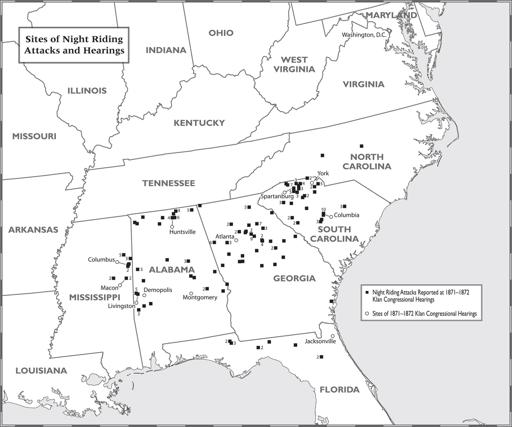

On a November night in 1871, some ten miles east of Aberdeen, Mississippi, Edward Crosby stepped outside to get some water for his thirsty child, when suddenly, he heard and felt the thunder of a team of horses. He gazed out, and by either moonlight or the glow of his torch, he saw about thirty disguised men descending on his home, their mounts draped by full-body cloth coverings.

Mrs. Crosbywho must have seen or heard the men approaching, tooasked Edward who and what they were. Edward had heard stories about armed white men on horseback galloping through the countryside and torturing and murdering Black families in the middle of the night during recent elections. The perpetrators and their apologists often referred to these raids euphemistically as visits, masking their brutality behind the veneer of a friendly social call. Edward told his wife he reckoned the gang heading for them was what people in their community called Ku-Klux, shorthand for the Ku Klux Klan.

In the spring of 1866, ex-Confederates in Pulaski, Tennessee, formed social clubs in which they sometimes donned masks or elaborate costumes and performed musical entertainment. They called themselves the Ku-Klux after the Greek word kyklos (circle) . Shortly after they organized, Klansmens activities evolved to roaming armed through communities in the middle of the night conducting paramilitary strikes on Black and white southerners. According to one historian, Klansmen harnessed nineteenth-century technology and organizational techniques which allowed more Klan groups to spread across the South.

That is why when Edward saw the costumed men and horses he concluded they were Ku-Klux. Worried that death was coming for him but hoping it would spare his wife and children, Edward slipped into his familys smokehouse. He thought the men might not think to look there, even if they decided to search the property for him.

When the posse arrived in the Crosbys yard, several men got down from their horses and called out for Edward to present himself. Although terrified, Edward retained his composure and stayed in his hiding place. Mrs. Crosby calmly told the men she did not know where her husband was, but she thought he had gone to call on his sister. The men hung around for a bit, dithering about what to do, before accepting they would not catch their target and leaving.

The Crosbys survived the raid but did not emerge unscathed. Secession and the founding of the Confederacy were less than a decade in the past; barely five years separated them from the end of the bloody Civil War. These mens arrival revealed to the Crosbys that Monroe Countys racially conservative whites had marked them as enemies. This terrified the family and left them afraid their lives would never be the same.

The visit was not Edward Crosbys first encounter with hostile white Mississippians. Before the war, enslaved people outnumbered free people in right to freedom.

In November 1871, African Americans in Monroe County tried to vote for progressive candidates and faced menacing opposition from whites who insisted that, if men like Edward cast ballots at all, they must be for white conservative candidates. Edwards landlordthe same man who had previously held him in bondageeven warned Edward that if he voted away white mens right to run Monroe County and rule over Black people as they saw fit, he would take Edward down. Edward dissembled, swearing to vote the way his employer wanted, but the suspicious white man promised he and his people would be on the lookout come election day.

Edward and other voters went to the polls, hoping to lift their preferred candidates to victory. They were part of a larger contingent of Black people working to make freedom real. Many of them had resisted or escaped slavery during the Civil War. For these Americans, the Emancipation Proclamation and Thirteenth Amendment were the first steps on the road to freedom, not the last. Freedom wasnt just about legal equality or the vote for them. It was about family and community. The franchise was a means to help Black families and communities achieve their goal: the end of any oppressive systems and practices that denied them their right to be free, equal, and secure.

Black freedom seekers had been behind the push for the civic, social, and political protections spelled out in the That act said all persons born in the United States were citizens, and positively affirmed that all American citizens were equally protected by all the nations laws. More specifically, the act said citizens, including Black people, had the right to make and enforce contracts and to inherit, sell, and hold property. In theory, at least, the Civil Rights Act granted Black people liberties denied to them in bondage and by racist restrictive laws. Men and women like the Crosbys saw themselves fine-tuning American freedom by making the nation live up to its creed and the promises spelled out in the founding documents.

At his polling place, Edward Crosby requested a Republican ballot, but he was told none were available. He waited, trying to figure out what to do and hoping an ally would show his face and give Edward the ballot he wanted to cast. None appeared. Edward hung around. Throughout the day, thirty to forty more Black men came to the polling place and asked to vote for the Republican ticket, all to be told the same thing.

Black men in Mississippi had read and understood the words all men are created equal in the Declaration of Independence; they believed in democracy and wanted to vote and run for office to secure their rights and advance their visions of freedom. These men knew the amended U.S. Constitution now recognized their right to do so. They also believed there should have been plenty of ballots available. But, locked in the southern planter classs viselike grip and fearing right-wing whites unleashed fury, the eager voters could not risk making a fuss. Edward tried voting at another polling place without success. I saw that I was beat at my own game, he said, and I got on my horse and dropped out. Edward was down but not yet defeated.

Frustrated by having his rights violated, and petrified his landlord and other white men would make good on their threats and continue to pursue him, Edward began planning to relocate. He did not know whether the man who had held him in bondage would have him whipped, like other Black men had been in his community, or drive his family off the land. He knew that if he resisted, the white man and his associates would kill him. All of us live a little in doubt, Edward said of his social circle. We didnt hardly know what to be at times.

White mens threats to Edwards life and the night riders visit to his home laid bare his familys precarious position. Edwards concerns were justified. When the men arrived at his door after he tried to vote, they brought with them white southern hate for who the Crosbys were and what their new lives and status as freed people represented. Whatever Edward and his wife thought they understood about surviving slavery and the Civil War was shaken that night, along with their faith in Reconstructions reimagining of Black peoples place in the nation. The visit exposed the freed familys disposability, dashing their postbellum dreams. The system of power that exposed Black families to this menacing violence infused the Crosbys home and took up residence in the souls of each of its occupants.

Next page