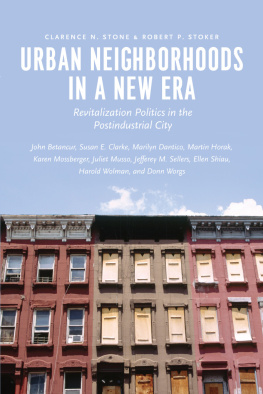

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

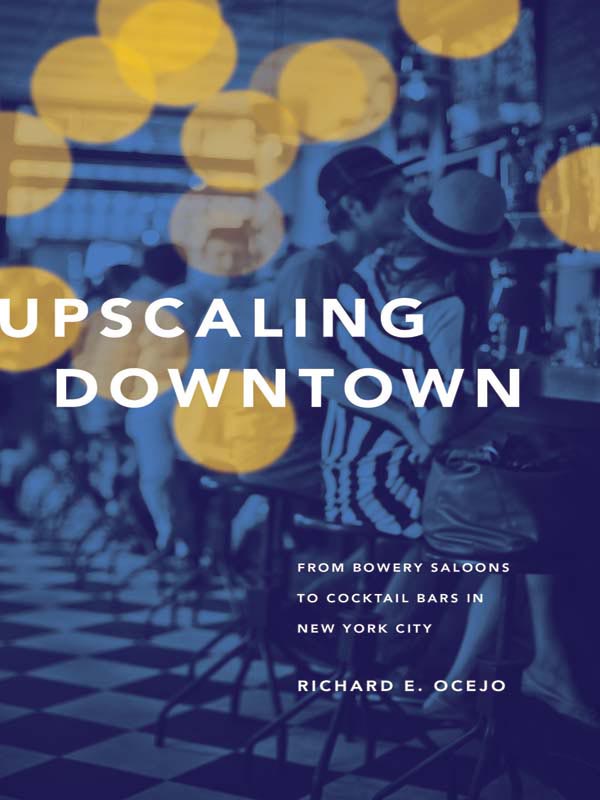

Jacket photograph: Love in the Lower East Side Reny Preussker.

Jacket design by Chris Ferrante.

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-15516-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014933832

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro and Avenir LT Std

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PREFACE

MILANOS IS A TINY OLD BAR ON HOUSTON STREET in downtown Manhattan, a block and a half from Bowery. Stuffed in the commercial storefront of a tenement building, the bar is long and narrow, and the decor is a messy mishmash of dusty objects, posters, signs, and old photographs of past and present customers. I first went there as a graduate student on a cold Tuesday night in February 2004. I had been having a drink with a friend at Botanica, a newer, hipster bar with DJs and secondhand furniture a few doors down. After my friend left, something about Milanos compelled me to go in and have one more for the road. I have always had a romantic affinity for old barsones with old men, cheap booze, and a smoky atmosphere. Based on what I had heard about the place, I assumed that is what I would find at Milanos. I was only half right.

When I walked in it was nearly midnight, and there were ten customers sitting at the bar. I ordered a beer and sat at one of the back tables. To my surprise, young revelers in their twenties were sharing the space with a couple of old men in their seventies. The older customers were sitting alone, staring into their beers, while others were in pairs, slightly intoxicated, playing the jukebox, and clearly enjoying their night. The bartender, a woman who looked to be in her early thirties, was friendly and talkative with all of them, making it hard to tell who was a regular customer. The bar clearly showed signs of a past, but it was also clear that something was different. I was intrigued by the place and its people, and decided to keep going back.

I studied Milanos over the next couple of years. I hung out at the bar often and got to know its regular customers and bartenders well. I also met dozens of patrons whom I never saw again and who were the way I was on my first night there: young, curious about visiting an old bar, and at their second bar of the night, or on their way to it. But the more I focused on the people and activities inside the bar, the more I was drawn towards its outside urban context. I identified three types of customer: older men who lived on the nearby Bowery, the citys most notorious skid-row district, and had been coming to the bar for many years; a group of younger regular customers, many of whom had moved to or often visited the neighborhood early on in its gentrification; and even younger visitors, in their twenties and thirties, who either recently moved to or lived outside the neighborhood and visited the bar infrequently. They all only shared the bar at the same time occasionally, and when they did they remained spatially separated. I recognized how each group represented a different stage in the bars and neighborhoods history, and how each group held different perspective towards both. As a result of my experiences at Milanos, I became intrigued by the idea of studying the transformations of downtown neighborhoods like the Bowery area and the nearby Lower East Side and East Village, especially how their changes affected their people, through an analysis of their bars.

These neighborhoodsbeing among New York Citys most storied and historichave been common sites for academic research, with their gentrification in particular serving as a popular focus. These studies have traced their history through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as places for numerous immigrant and working-class groups, to rundown and crime-ridden slums and skid rows, to countercultural and avant-garde arts scenes, and, finally, to popular, gentrifying places for young urban professionals to live. From them we have learned much about the political economy of the gentrification of downtown neighborhoods, the roles of culture and images in their transformation, and the reactions of their residents to gentrifications onset. But these studies possess two shortcomings that I want to address in this book: their analytical time frame stops before the economic boom of the 2000s, when these neighborhoods transformed into destinations with large nightlife scenes; and they do not consider how the commercial dimension of gentrification, particularly new bars and nightlife, have affected them. Given how it had changed, Houston Street just off Bowery was a strange place to still find an old bar for old men in the mid-2000s. The fact that Milanos was still around, but with a tremendously varied clientele, amid a popular nightlife scene, and in an area that was becoming more and more upscale in terms of its residential and commercial exclusivity, inspired me to explore the relationship between downtown Manhattans bars and their surrounding urban context.

Downtown streets clearly show the mixture of the old and the new, the signs and symbols of the past and the present, in everyday social life and in the built environment. I was always struck by the social contrasts I found at different times of day. During the daytime, lifelong Latino and new, young white residents pass each other on sparsely populated sidewalks. Inexpensive bodegas sit next to upscale hair salons and storefront galleries showing high-priced artworks by internationally recognized artists. Sunbeams bounce off the shiny facades of new condominiums. The grungy bricks of the revalorized nineteenth-century tenements from across the street are reflected in their mirrored glass. In Tompkins Square Park, in the heart of the East Village, homeless people huddle on benches and form a line for food from a nearby church, while young residents chat with their neighbors in the busy dog runs and sip expensive coffees at sidewalk cafs.

If downtown Manhattan features a quiet balance of old and new during the day, the nighttime tells a different story. At night the area teems with activity as the population swells. The narrow streets become crowded thoroughfares for vehicles and pedestrians. The people are overwhelmingly young, some are stylishly dressed and others casually so, and most are white. I regularly overheard revelers talking about which bar to go to next and where it is located, people in groups telling each other stories of previous nights of revelry, and couples bickering. It turns out that the steel barricades blocking so many of the storefronts during the day do not signify failed businesses in a blighted area, as they once did in many downtown neighborhoods. At night the barricades are up, and light and sound pour out from bars, restaurants, lounges, and clubs onto the sidewalks. Lured by nightlife establishments, the citys youth turn downtown into a place for nighttime consumption and amusement. Today when the sun goes down, these neighborhoods come alive in a dramatic way, and the notion that downtown has become a destination comes through, clear and loud.