Engines of Diplomacy

2016 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Alegreya Sans by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

Portions of the text were previously published, in substantially different form, in The Main Mean of Their Political Management: George Washington and the Practice of Indian Trade in the Early Republic, in George Washington in and as Culture, edited by Kevin Cope (New York: AMS Press, 2001), and in A Commercial Embassy in the Old Northwest: The U.S. Indian Trading Factory at Fort Wayne, 18031812, Ohio Valley History 8, no. 4 (Winter 2008): 116, reproduced here with permission.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nichols, David Andrew, 1970

Engines of diplomacy: Indian trading factories and the negotiation of American empire / David Andrew Nichols.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4696-2889-9 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4696-2689-5 (pbk: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4696-2690-1 (ebook)

1. Trading postsUnited StatesHistory. 2. Indians of North AmericaGovernment relations17891869. I. Title.

E 93. N 5 6 2016

323.1197dc23

2015032056

To Corinna Nichols

Soror et Scholastica

Contents

Illustrations, Maps, and Tables

Illustrations

Selected Peltry Shipped from Tellico, 1797, 1799, and 1801

Sugar Camp, by Seth Eastman

Fort Osage factory building

Gathering Wild Rice, by Seth Eastman

Portrait of Thomas McKenney

Maps

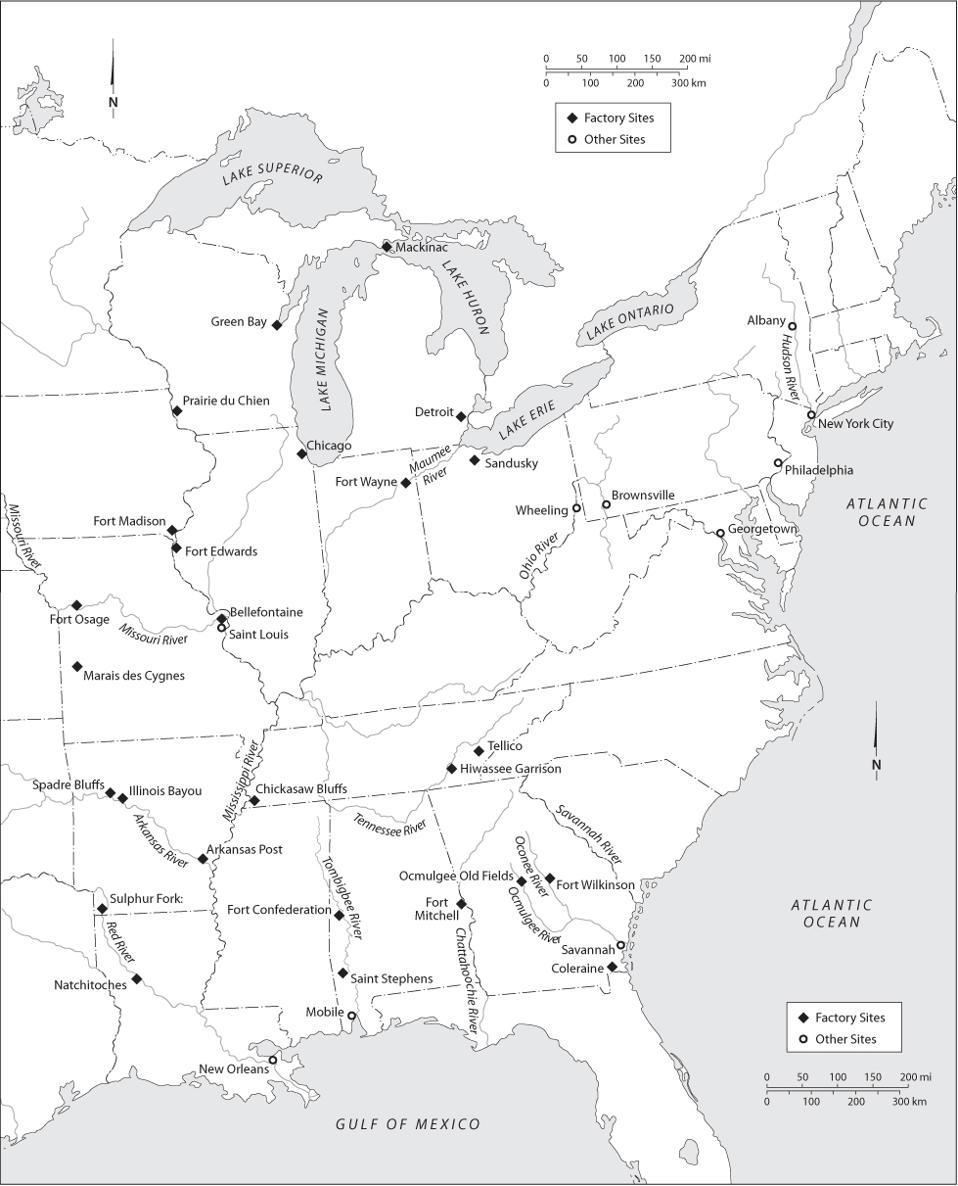

The Northern Factories xiv

The Southern Factories xv

Tables

3.1 Selected Sales to the Natchitoches Factory, 18061811

4.1 Selected Shipments from the Office of Indian Trade, 18031811

4.2 Freight Costs for Selected Factory Supply Routes, 18071810

4.3 Sales of Indian Wares by the Office of Indian Trade, 18051811

4.4 Sales by the Office of Indian Trade, by Market, 18051812

5.1 Indian Products Shipped by the Fort Osage Factory, 18091813

5.2 Indian Wares Shipped by the Fort Madison Factory, 18091813

5.3 Selected Shipments from the Chicago Factory, 18071811

6.1 Selected Shipments from the Office of Indian Trade, 18121815

6.2 Office of Indian Trade Produce Sales, 18121815

7.1 Selected Shipments from the Office of Indian Trade, 18161821

7.2 Sales of Indian Wares to All Factories, 18151819

Acknowledgments

Books like this one could not exist without the dedication, skill, and professionalism of librarians and archivists. For the present volume I am deeply indebted to the staff of the National Archives in Washington, D.C., which holds the Records of the Office of Indian Trade. I am also grateful to the employees of Cunningham Library at Indiana State University; the Filson Historical Society in Louisville; the Historical Society of Pennsylvania; the Library Company of Philadelphia; the Missouri Historical Society Library and Research Center; the Ohio Historical Society; and Young Library at the University of Kentucky.

I have presented parts of this book to colleagues at the annual meetings of the Indiana Association of Historians, the Missouri Valley History Conference, and the American Society for Ethnohistory, as well as a Social Science Research Colloquium at Indiana State University. I gratefully acknowledge the thoughtful questions and comments provided by Stan Buchanan, Brian DeLay, Nicole Etchison, Chris Fischer, Richard Lotspeich, Dennis Smith, Russell Stafford, Kylei Tumey, Bassam Yousif, and Keri Yousif. Indiana State University provided travel funds to help me attend the first and third of these conferences. My colleagues in ISUs Department of History have been supportive of this project since its inception and have helped make Indiana State a welcome professional home.

Don Hickey, the dean of War of 1812 scholarship, kindly read and commented on an earlier version of Chapter 6, which is much stronger for his input and insight. Two anonymous readers gave the entire manuscript an equally thorough and incisive critique. The book would be a much poorer one without them. At the University of North Carolina Press, Mark Simpson-Vos has proved a master of the academic editors art, and has been generous with his time and support since we first discussed this project a decade ago. Thanks are equally due to Lucas Church, Stephanie Wenzel, Jad Adkins, and Susan Garrett for their diligent editorial and marketing work, and to Christy Hosler and Westchester Publishing Services for their copyediting expertise.

Portions of Chapters 1, 2, 5, 6, and 8 of this book have appeared in print before, as A Commercial Embassy in the Old Northwest: The U.S. Indian Trading Factory at Fort Wayne, 18031812, Ohio Valley History 8, no. 4 (Winter 2008), and The Main Mean of Their Political Management: George Washington and the Practice of Indian Trade in the Early Republic, in George Washington in and as Culture, edited by Kevin Cope (New York: AMS Studies in the Eighteenth Century, 2001). I thank AMS Press and the editors of Ohio Valley History for permission to reprint these materials.

This project first germinated in a graduate research seminar led by Michael Green at the University of Kentucky, and his enthusiasm for my study of the U.S. trading factories ensured that I would see the project through to completion. Mike took the time to read the first draft of the manuscript cover to cover, and he helped me make it a leaner and clearer book. I am glad he had the chance to see my work before his untimely death in 2013. Theda Perdue and several of her and Mikes brilliant students, notably Cary Miller and Christina Snyder, were all professional role models for me. My partner, Susan Livington, my brother Patrick, and my sister Corinna have provided years of support and encouragement. My sister, in particular, has listened too often to my weary descriptions of copying old invoices, remarking on one occasion that Im sure someones been doing the same sort of thing since the Sumerians. To her, appropriately, I offer this books dedication.

Engines of Diplomacy

U.S. Indian Trading Factories, and Associated Supply and Marketing Centers, 17961822. Maps by Bill Nelson.

Introduction

Small and shaky as it was in the 1790s, the early American national government did not lack audacity. In 1795 it began an ambitious experiment in public enterprise: a system of federally funded trading posts that grew over the next dozen years into a far-flung network, extending from Fort Wilkinson in Georgia to Mackinac Island in the northern Great Lakes to Fort Osage on the Missouri River. The posts, known as factories, purchased Native Americans animal pelts and other wares at prevailing local prices, and sold them goods at lower prices than those charged by private traders. The founders of the factory system, in particular President George Washington, hoped that the factories would tie Indian nations to the United States with cords of economic interest, and at the same time drive unscrupulous private peddlers and scheming British traders out of business. Thanks to Congressional support, the system survived the embargo of 18079 and the War of 1812though British soldiers and Indian warriors destroyed several factories during the warand the last trading houses remained open until 1822, when Congress voted to shutter them.