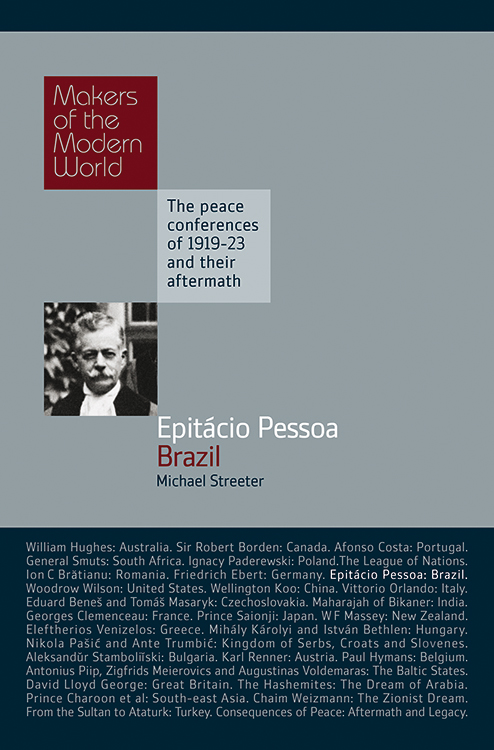

Preface

The journey had begun in high spirits and with great hopes. The Curvelo set sail from Brazil on 2 January 1919 with former government minister and judge Epitcio Pessoa on board. His destination was Paris, where he was to serve as the head of his countrys delegation to the historic Peace Conference convened to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. As the ship slipped out of harbour the mood was upbeat, not least because this was a rare chance for Brazil to play a role on the world stage. As one of the belligerent powers on the victorious Allied side it had been rewarded with the right to have three full delegates at the Conference more than most of the other countries attending.

By late January, however, the mood on board the Curvelo had turned to one of frustration and irritation. The sluggish vessel had chugged so slowly across the Atlantic that the Conferences opening ceremonies on 18 January had come and gone with the greater part of the Brazilian delegation literally all at sea. There was a certain irony about this particular ship hampering the progress of Pessoa and his team, one that was not lost on those on board. In her previous life the Curvelo had been known as the Bremen and was one of more than 40 German ships the Brazilians had confiscated during the war. It was the ownership of those ships that was one of the two most pressing issues that the Brazilian delegation hoped to resolve at the Conference if they ever got there. In a way, the other matter involved German ships also it concerned the fate of a large consignment of Brazilian coffee that had been trapped in German ports at the outbreak of the war back in 1914.

As the Curvelo limped slowly into Lisbon harbour, the final stretch of the journey nearly in sight, Pessoa could have been forgiven for thinking the worst was over. But in the Portuguese capital the head of the Brazilian delegation heard the tragic news that their countrys president Francisco de Paula Rodrigues Alves had died. It was true he had been ill for some time, so his death came as no great surprise. But the loss of a genuinely popular head of state on the eve of such an important conference was still a blow to morale. As the Curvelo finally brought Pessoa and his entourage into French waters on 28 January, it may even have seemed as if their diplomatic mission was jinxed. Neither he nor his fellow delegates could know that, on the contrary, the fortunes of both the delegation and more especially Pessoa himself were about to take a dramatic turn for the better.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Professor Linda Lewin for her help and encouragement in the research for this book.

Creation of the Republic: 18891900

Ever since Portuguese sailors landed there at the start of the 16th century, Brazil has been stuck one might say burdened with the label of a country of the future. It is not hard to see what attracted those Europeans and why it was felt the country offered so much potential. The coastline provided an easy supply of the valued brazilwood (hence the countrys subsequent name) a tropical climate, natural harbours and an abundance of wildlife. In more modern times the countrys fertile soils have produced sugar, rubber, coffee and most recently ethanol, while underground and off the coast considerable reserves of oil and natural gas have now been discovered.

The raw, physical statistics of Brazil never cease to amaze. Jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean towards Africa, it occupies some 8.5 million square kilometres or more than 3.2 million square miles, making it the fifth largest country on Earth. Its vast 4,600-mile coastline runs from French Guiana in the north to Uruguay in the south and on land it has boundaries with ten other countries. Only two South American countries, Ecuador and Chile, do not share a frontier with Brazil. Then there is the mighty Amazon river, the worlds largest river in terms of volume. More controversially, Brazilian experts now claim it as the worlds longest river too, eclipsing the Nile. The countrys population is also impressive in scale, standing at around 190 million by 2009.

Yet on the eve of the modern era of Brazil, which started in the final decade of the 19th century, this South American colossus seemed as far as ever from fulfilling the potential that had so long been predicted for it. Its contacts were largely with Europe where this former Portuguese colony it became independent in 1822 was seen, notably by the British, as a useful source of basic raw materials, a destination for poor immigrants and worthy of some modest investment but little else. In return the Brazilian elite looked to Europe for much of their intellectual, cultural and political inspiration. The United States, the dominant force in the Western hemisphere but self-absorbed with its westward expansion after the horrors of its Civil War, paid Brazil little serious attention. Even some of Brazils South American neighbours had relatively little to do with this large but underpopulated country of 14.3 million people on their doorstep.

THE PEOPLES OF BRAZIL

When the Portuguese first began arriving in Brazil in the early 16th century there was a sizeable indigenous population of perhaps around three million. However, in such a vast country the Amerindians were scattered relatively thinly. One group of peoples is known collectively as the Tup-Guaran, who between them occupied points all along the Brazilian coast and the Amazon river. Another group is known as the Tapuya. Some anthropologists prefer to classify the indigenous peoples of the country according to the terrain they lived in and the lifestyle this afforded them. The two main groups were divided between those living in tropical forests, who survived by agriculture and fishing, and those living on the plains and more arid areas, who hunted, fished and gathered their food. However they are classified one thing is clear: the Amerindians suffered enormously from the arrival of the colonists, through disease, loss of land and enforced labour. As for the settlers, many initially marvelled at the simplicity and apparent innocence of the native inhabitants lives. The Portuguese also learnt from them; for example, how to grow new crops such as manioc. Though the colonists tried to put the Amerindian population to work on plantations, they were generally regarded as unsuitable, a factor that ultimately led to the importation of African slaves. Thus a third racial group arrived in the country, to go with the white Europeans and original inhabitants. Out of these sprang a mixed-race people, initially the product of white men and Amerindian women, known as cabolos, while later the mix became one between Africans, Amerindians and whites. In the late 19th and early 20th century it was generally accepted in Brazil that the whiter a person was the better, and it was also widely believed that society itself was whitening. In 1890 whites made up an estimated 44 per cent of the population.

The reasons the country had such a minor role on the world stage at this time were partly geographic, partly cultural. Brazil was the only Portuguese-speaking colony in South America and this fact alone has always set it apart from its mostly Spanish-speaking neighbours. Under the famous Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494 Spain and Portugal had carved up the world to determine which of them would control any new lands they discovered. The only portion of South America that lay on Portugals side of this line was the then-unknown Brazil. Another difference was that Brazil remained a monarchy long after the former Spanish colonies had become independent republics in the first half of the 19th century. Moreover, nature had conspired to further isolate Brazil from its neighbours, not just by the Amazon jungle but the river systems of both the Amazon in the north and the Paraguay-Paran-Plata rivers to the south. Its closest relations and rivalries were with Uruguay, Paraguay and Argentina to the south. Finally, the winds and currents of the Atlantic Ocean made it easier to sail between Europe and Brazil than between Brazil and the United States, something that remained a significant factor until the era of sail gave way to that of steam.