This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.org

2022 by Anat Plocker

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2022

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

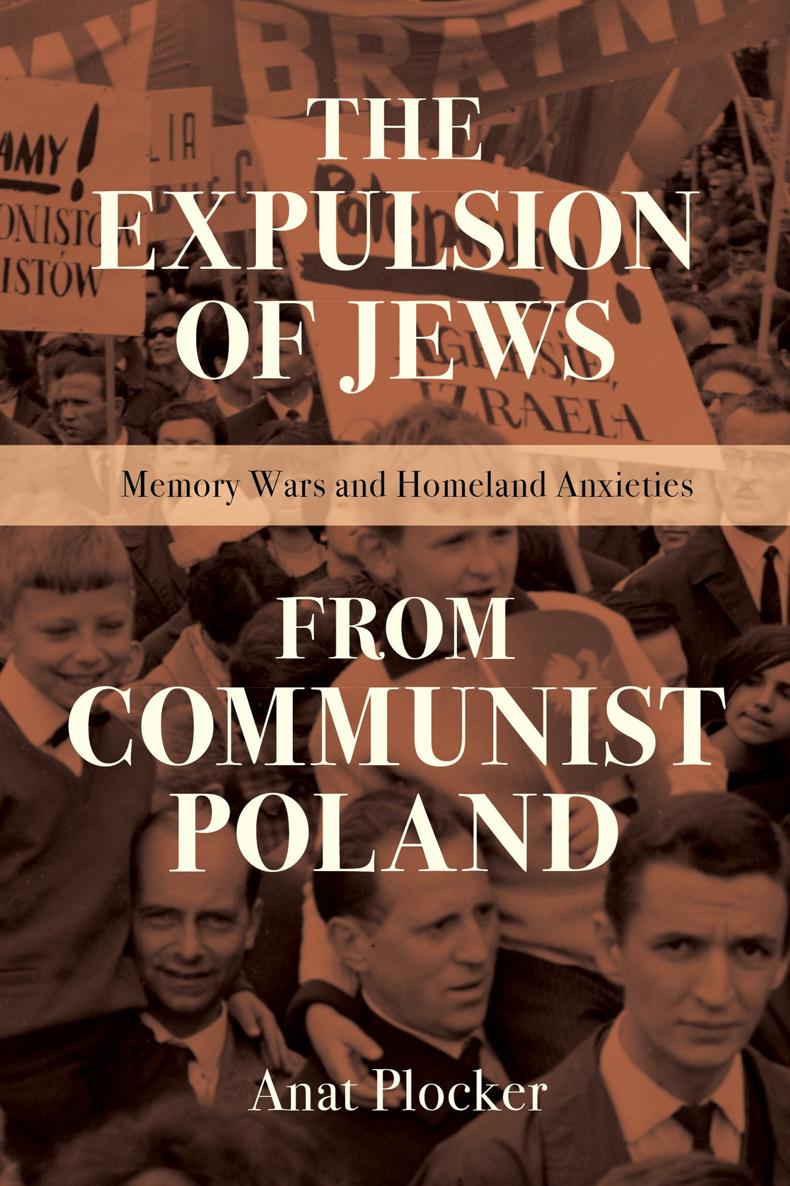

Names: Plocker, Anat, author.

Title: The expulsion of Jews from communist Poland : memory wars and homeland anxieties / Anat Plocker.

Description: Bloomington : Indiana University Press, 2022. | Series: Modern Jewish experience | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021028665 (print) | LCCN 2021028666 (ebook) | ISBN 9780253058652 (paperback) | ISBN 9780253058669 (hardback) | ISBN 9780253058645 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: JewsPolandHistory20th century. | PolandHistoryMarch Events, 1968. | AntisemitismPolandHistory20th century. | PolandPolitics and government1945-1980. | CommunismPolandHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC DS134.55 .P57 2022 (print) | LCC DS134.55 (ebook) | DDC 943.8/004924dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021028665

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021028666

M ICHAEL S FARD, A WELL-KNOWN I SRAELI HUMAN RIGHTS LAWYER , and his law firm have litigated in the last fifteen years hundreds of cases pertaining to the everyday lives of Palestinians living in the territories occupied by Israel. Michael is the grandson of the Polish Jewish poet David Sfard and the film scholar Regina Dreyer-Sfard, on his fathers side, and of the author Janina Bauman and the renowned sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, on his mothers, all of whom the Polish state forced out of Poland following the March 1968 events, along with Michaels parents, Anna and Leon. Their family story is told in Janina Baumans memoir of the period, A Dream of Belonging (1988). In 1968, Leon Sfard, a political activist at Warsaw University, was jailed for a few weeks for his involvement in the dissident student movement. Fifty years later, in 2018, Michael said in an interview for a British website, It [his fathers involvement in March 1968] undoubtedly had a very big impact on me. Our home was very political, and I grew up with the principle that you should do the moral thing, even at a cost. In a 2009 article for the Israeli daily Haaretz entitled Back to Warsaw 1968, Michael wrote:

I saw the military prosecutor speaking with pathos about the need to keep him [Mohammed Khatib, one of the Palestinian leaders of the Bilin protests] in custody, about his being a security risk. Just like my father and his friends in Warsaw in 1968, when they organized demonstrations against the regime and for democracy. There, too, the authorities arrested the leaders of the protest in an effort to make them disappear. There, too, the arrests were made in the predawn hours. There, too, there were police officers who made the arrests, secret service agents who carried out the interrogations, prosecutors who prosecuted and judges who judged. And there, too, each one was a small but essential cog in a huge machine whose purpose was the control and oppression of millions.

Michael concluded, Warsaw 1968 is not like Bilin in 2009, the conflict is different, the world is different, but there is something similar in all attempts to oppress human beings. In his book The Wall and the Gate, Michael explains that he has taken up the Palestinian cause because Palestinians in the Israeli occupied territories have no citizenship status. In 1968, his parents and grandparents, for a short period, had no passports and no citizenship; the Polish communist government had issued them one-way travel documents and illegally stripped them of their citizenship. In many ways, this book explores the story of the Sfard/Bauman family, as they played important roles in the history of both the Jewish community and the Polish dissidents. It analyzes the process by which state authorities deprive citizens of their citizenship, how the cogs in the machine turn a minority into a security threat and force people out of their homeland. And it traces a story of the triumph of nationalism over citizenship rights and equality. Unlike Adam Michniks assertion that the March events were a dry pogrom, a story typical and at the same time unique to Jews, this book shows that the anti-Jewish campaign in 1968 is an integral part of the modern history of Europe and of nationalism.

The study of the March Events in Poland has been, for me, a personal and academic exploration, a family history as well as an intellectual journey. My family was also forced to leave in 1968: my mother, then a student at Warsaw University, my grandparents, and my teenage uncle all immigrated to Israel in 1968; my father and his family moved to Israel from Poland in 1957. My maternal grandparents, Jzef and Mania, had been prewar communists who, according to family myth, met at a party function. They escaped to the Soviet Union in 1939, fleeing the German invasion, and as communists, they returned to Poland when the war ended. My grandfather, Jzef Goldkorn, worked for the TSK, the Social Cultural Association of Jews in Poland. He had risen to prominence in the Upper Silesia section, where he became head of the local TSK. When they moved to Katowice in 1946, the Polish authorities in Upper Silesia were busy expelling ethnic Germans from the region, as part of the ongoing mass deportation of millions of Germans out of the newly acquired western territories of the state. Anti-Jewish violence also swept Poland at the time, as the state aimed for a homogenous Poland within its new borders. Twenty years later, my grandparents and their children moved to Warsaw, where my grandfather wrote for Folks Sztyme, the Yiddish-language daily, until the state forced him out of his job and his country as well.

A few years after I had begun working on this project, my uncle, Wodek Goldkorn, published in Italian (and later in Polish) a literary memoir of his childhood in Poland entitled A Child in the Snow. In it, he describes my grandparents attachment to communist Poland: Now... we are at home [u siebie]. In a world that places ethnic-national identity above all others, however, such dreams of belonging have little chance of coming true. Their Poland showed them the door.

I owe my existence perhaps to Wadysaw Gomuka, the first secretary of the Polish communist party (the Polish United Workers Party), since he encouraged Jewish immigration to Israel throughout his reign and my parents met in a circle of Polish-speaking friends in Bat Yam, a city just south of Tel Aviv, in the late 1960s. In 1967, Gomuka went as far as to urge Jews to choose a homeland, rejecting the idea that Polish Jews could be just that, Poles and Jews, not one before the other. For some, like Leon Sfard, this led to immigration to Israel, for living in Sweden or America, or somewhere like that, would be like being a tourist for your entire life.

![Communist Party of PeruCommunist Party of Peru - Shining - The Collected Works of the Communist Party of Peru. 1968-1999 [Warning: Hate Speech and Negationism]](/uploads/posts/book/267146/thumbs/communist-party-of-perucommunist-party-of-peru.jpg)