This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1923 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

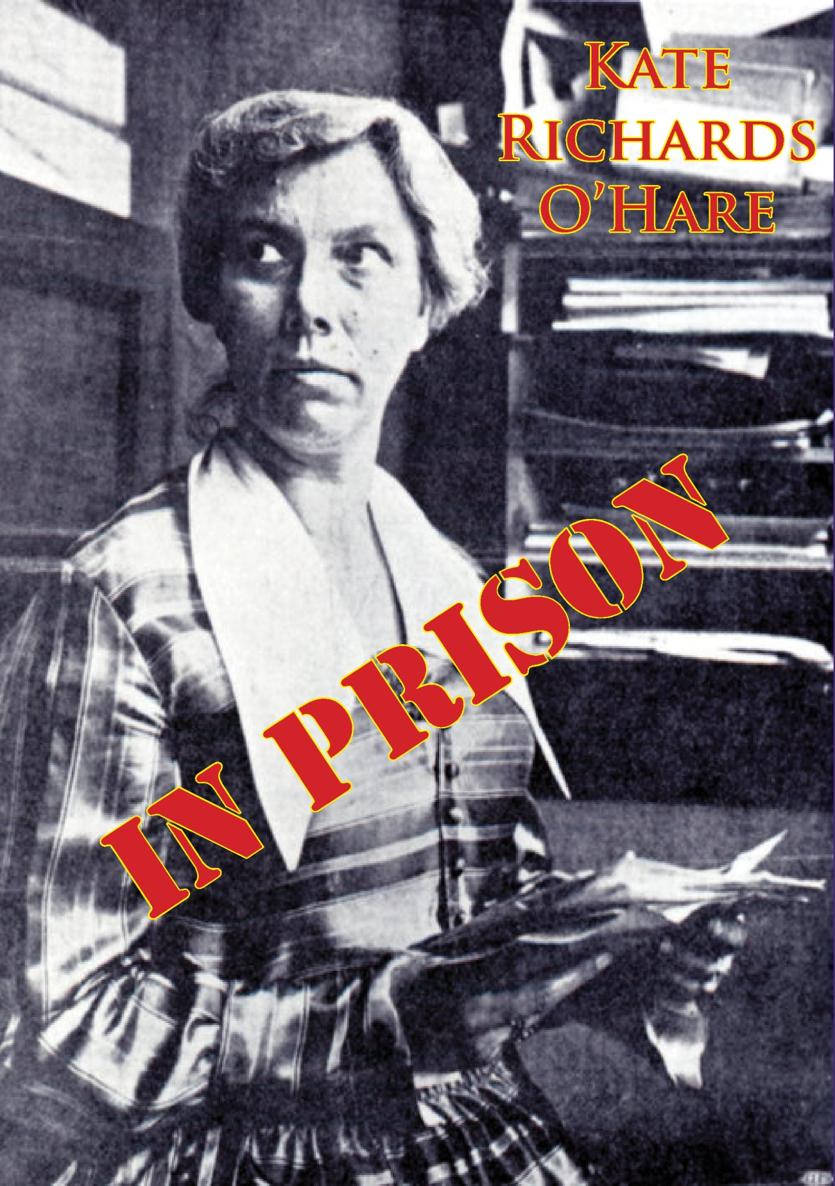

IN PRISON

by KATE RICHARDS OHARE

Sometime Federal prisoner number 21669

FOREWORD

Political prisoners have often been torch-bearers who carried the light of truth into dark places and illuminated the hidden things of the existing social order. The old slave-masters chopped off the heads of political offenders, the feudal lords boiled them in oil, kings and emperors exiled them, and the older capitalist governments of Europe sent them to prison.

But these older capitalist governments were wise in their day and generation. They recognized the fact that political prisoners were quite different from ordinary felons and treated them accordingly. In European countries political offenders were not as a rule handled by the same judicial machinery as ordinary offenders, they were not imprisoned with them, and in every way they were something apart from other convicts.

The United States is a youthful nation, callow, brash, and arrogant, as youth is prone to be, conceited in its sense of power, and boastful of the fact that it could well afford to permit the free expression of any shade of opinion. Not until we entered the World War did our ruling class feel it necessary to imprison people for holding dissenting and disturbing economic and political beliefs, or place the term political prisoner in our American vocabulary.

As an ex-political prisoner I feel no bitterness towards the industrial and political groups which sent me, and hundreds more like me, to prison. There was really nothing else which they had the intelligence and the social vision to do.

A political party is elected to power in the United States on the representation that it is the most efficient protector of a social system based on the sacredness of profits. And we pioneer political prisoners insisted on telling the common people the unpleasant truths as to how, and why, war is, for the owners of industry and the bankers, the greatest profit-maker known to man.

We knew, or thought we knew, the relations of profits to war, and we insisted on telling it to everyone who could be induced to give us his ear. We told what we knew, or thought we knew, in season and out, we whispered it and shouted it from the housetops, we expounded it in highbrow literature and gave it punch for the common man of the streets by couching it in lowly slang. We talked war and profits, war and profits, war and profits, until the administration was compelled in sheer self-defense to make some attempt to silence us. There were in the balance too many billions in war profits in 1917 to permit the free discussion of war and profits.

The Constitution of the United States was the first casualty of the war. Constitutions, if really democratic, always are, for democracies are poor war-makers; only a despotism can be an efficient war-making machine.

By the stroke of a pen the Postmaster-General slew the free press, and practically the entire radical press was destroyed. But those of us who do not believe that great social problems can be solved by war could still talk, if we could not publish newspapers, and many of us did talk. The best method which the intelligence of the existing political administration could devise to silence the talkers who insisted on talking about war and profits, was to send them to prison. Possibly because our law-makers lacked the experience and the wisdom of the older European governments, they attempted to penalize the expression of opinion in exactly the same way as the commission of other crimes. Our government also attempted to handle the crime of expression of opinion with the ordinary judicial machinery; it committed political prisoners to the same prisons, and handled them in the same way, as ordinary felons.

The results gained from placing many hundreds of political prisoners in our penitentiaries have not been quite those sought by the political administration in power, or by the industrial forces controlling the administration. No disturbing talkers opinions were changed ever so little by his being punished for expressing them, and the senselessly drastic punishments given by the courts denoted only abject panic on the part of the ruling class and gave added weight in the public mind to the penalized opinions. The facts of war-time profits as causative factors in making war were not discredited in the least, and what really happened was that the talkers had a wider and more sympathetic audience than ever before. And, as a by-effect, the searchlight of intelligent study and keen analysis has been turned into the darkest and most noisome depths of our social systemour prisons.

E. Stagg Whitin, in his introduction to The Prison and the Prisoner, says

Penology, criminology, etc., have been speculations of the wise in their own conceits. The prisoner has remained an abstraction to be babbled about, though never really known a thing apart, disowned, investigated at arms length for fear that the contagion might possess the investigator.

The humanness and fallibility of the convicted and the unconvicted alike have raised up barriers between the prisoner and those who attempted to study him. His criminal characteristics, his love of evil, and the outlawry of his practices have all been discussed in the third person, but it has been dangerous to admit that he is simply a man like ourselves, the difference being that a chance turn of the wheel of justice has singled out one of his acts and condemned it with the power of the law. But a new day has dawned for the prisoner. At last we look at ourselves!

Having brought the study of the prisoner to the basis of scientific reality, having divorced from our discussion the thought of our own superiority and having sought the interpretation of the problem from the only one who can really interpret itthe prisoner himselfwe can feel that our efforts will reach the heart of the problem, that our rising knowledge will help lift the whole superstructure of society.