The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg

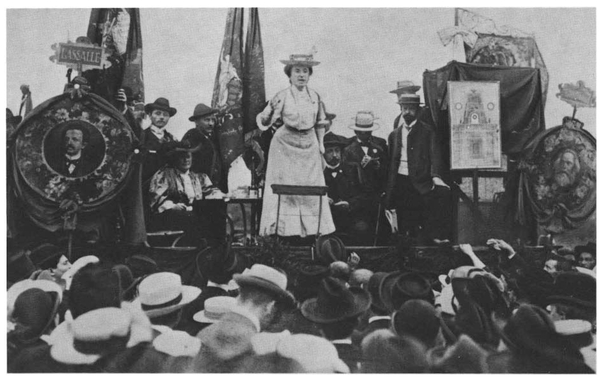

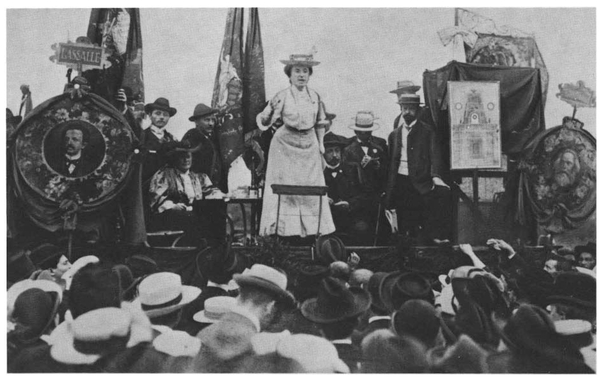

Rosa Luxemburg addressing a rally. The pictures on either side of her are of Lassalle and Marx. (Courtesy Dietz Verlag)

The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg

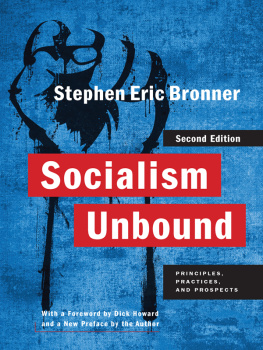

edited and with an Introduction

by Stephen Eric Bronner

with a Foreword by Henry Pachter

First published 1978 by Westview Press, Inc.

Published 2019 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1978 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Luxemburg, Rosa, 1870-1919.

The letters of Rosa Luxemburg.

1. CommunistsCorrespondence. I. Bronner, Stephen.

HX273.L83A4 1978 335.430922 78-17921

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-29353-6 (hbk)

On January 15, 1919, mercenaries of the counterrevolution murdered Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, the two leaders of the Spartacus uprising. One year later, a small volume of Rosa Luxemburg's "Letters from Prison" appeared in print. These were addressed to Liebknecht's wife Sonja, while Karl was at the front and then in jail, and they showed the dreaded "Red Rosa" as a warm and sensitive woman who was concerned with the birds she watched from her cell, romantic poetry, and the worries of her friends. In short, they showed Rosa Luxemburg to be human.

Three years later, her friend Luise Kautsky published the letters that Rosa Luxemburg had sent to her and her husband over the years. Karl Kautsky had been the theoretical panjandrum of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the editor of its prestigious journal, Die Neue Zeit, He and Rosa Luxemburg had at first been comradesin-arms on the party's left but then quarrelled over many issues including the timid course taken by the journal, the mass strike and, finally, the party's support of the Kaiser's war. Nevertheless, Luise erected this monument to her mourned friend. Rosa Luxemburg's criticisms of Kautsky emerge from those letters, andyetone hears once again the voice of a tender individual whose heart beat as much with her private circle of intimates as with the great causes of mankind.

After Luise's death, her son Benediktwith whom Rosa had played when he was a childdiscovered another bundle of letters. Some of them revealed her budding love for a younger man, Hans Diefenbach, while the collectio"n as a whole permitted an even greater appreciation of her multifaceted nature. Benedikt Kautsky was able to publish these letters after World War II, and soon thereafter the Polish Communist partyreleased two volumes of Rosa Luxemburg's letters to her first love and permanent political mentor, Leo Jogiches. Then too, Charlotte Beradt published Rosa's intimate letters to her secretary Mathilde Jacob, which illuminate the everyday cares and needs so much a part of one's life. Finally, I understand that about a thousand letters still lie in the archives of the Institute for Marxism-Leninism in East Berlin.

I have always wanted the human face of this great revolutionary to be made more visible to the general public. It is this that the present volume seeks to accomplish. In it we see the woman, the lover, the companion, the friend of nature and poetry, the prisoner who charms her jailer, the employer, the cook, and, of course, the political activist.

A number of things were necessary for the completion of this collection. First, the letters had to be selectedbut the temptation to display all the riches that might overburden a book of this sort had to be resisted. Secondly, there was a need for new translations on account of the unsatisfactory original rendering of the texts. In this respect, Stephen Eric Bronner and Hedwig Pachter have labored hard to do justice to the spirit of the letters while making the translations readable. Finally, the letters themselves had to be placed within a context. To this effect Professor Bronner has contributed a brilliant introduction, in which he explains Rosa's life and thought and why it is time for this continent to receive her message.

I very much hope that Rosa Luxemburg will find a better reception in this country than she did in her own. In Poland and East Germany, she is thought of as a martyr and a saint, duly celebrated on appropriate state occasions. In West Germany, her picture graces a postage stamp, but not even the Young Socialists march under her name. The irony has been grippingly expressed by the young poet Peter Steinbach, who fled East Germany in 1958.

Somewhere behind the Red City Hall

Stands

the entire Central Committee

before your remains

MEMORIAL ROSA

Those who here bend their heads

Shoot at

Whoever thinks differently

Or would like to live elsewhere

And they conclude contracts

with those who

Oh Rosa-on-the-post-stamp

lick your behind

after nosily justifying themselves

Has mankind

Ever sunk so low?

Henry Pachter

If Rosa Luxemburg's entire correspondence were compiled, it would surely amount to at least six huge volumes. To a certain extent, of course, any selection procedure contains an arbitrary element, but the difficulty is increased when one considers that certain collections of Rosa Luxemburg's lettersall of which were compiled after her deathsought to emphasize a particular aspect of her personality to the detriment of other facets.

The purpose of this collection, however, is to show the personality of Rosa Luxemburg in its political as well as in its personal dimensions. Consequently, the selection of these letters involves an attempt to present the spirit of her time as it is reflected in her political thinking, activism, and personal concerns. This intent dictated the criteria used in the selection process; thus, letters that relate to truly minor political incidents have been eliminated along with those that are repetitive or deal with everyday occurrences of secondary interest.

The benefit that has been derived from the two major biographies will be obvious, both in the introduction and in the evaluation of the letters. The earlier book by Paul Frohlich, a founder of the German Communist Party (KPD) who later became the leader of the German Socialist Workers' Party (SAP), is oriented towards Rosa Luxemburg the public figure. The second biography, Peter Nettl's two-volume work, is the standard work dealing with all aspects of Rosa Luxemburg's life and career.

The main sources of the letters compiled in this collection are the following: Briefe aus dem Gefngnis (Berlin 1920); Briefe an Karl and Luise Kautsky (Berlin 1923), which was translated by Louis P. Lochner as Letters to Karl and Luise Kautsky (New York 1923); "Aus den Briefen Rosa Luxemburgs an Franz Mehring," edited by F. Schwabel, Internationale 2, no. 3 (1923):67-72; "Unbekannter Brief Rosa Luxemburgs. Als Rosa aus dem Gefngnis kam..." Rote Fahne, 18 July 1926, no. 165, Supplement p. 1; Briefe an Freunde, ed. Benedikt Kautsky (Hamburg 1950); "Einige Briefe Rosa Luxemburgs und andere Dokumente," Bulletin of the International Institute of Social History 8, no. 1 (1952):9-39; W. Blumenberg, "Einige Briefe Rosa Luxemburgs," International Review of Social History 8, pt. 1 (1963):92-108; Gotz Langkau, "Briefe Rosa Luxemburgs im IISGEin Nachtrag," International Review of Social History 21, pt. 3 (1976):413-494; Briefe an Leon Jogiches, ed. Feliks Tych (Frankfurt/Main 1971); Rosa Luxemberg im Gefngnis, ed, Charlotte Beradt (Frankfurt/Main 1973); Vive la Lutte: Correspondance 1891-1914, ed. Georges Haupt et al. (Paris 1976); and J'tais, j suis, je serail: Correspondance 1914-1919, ed. Georges Haupt et al. (Paris 1977).