Copyright 2019 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Jacket design: Graciela Galup

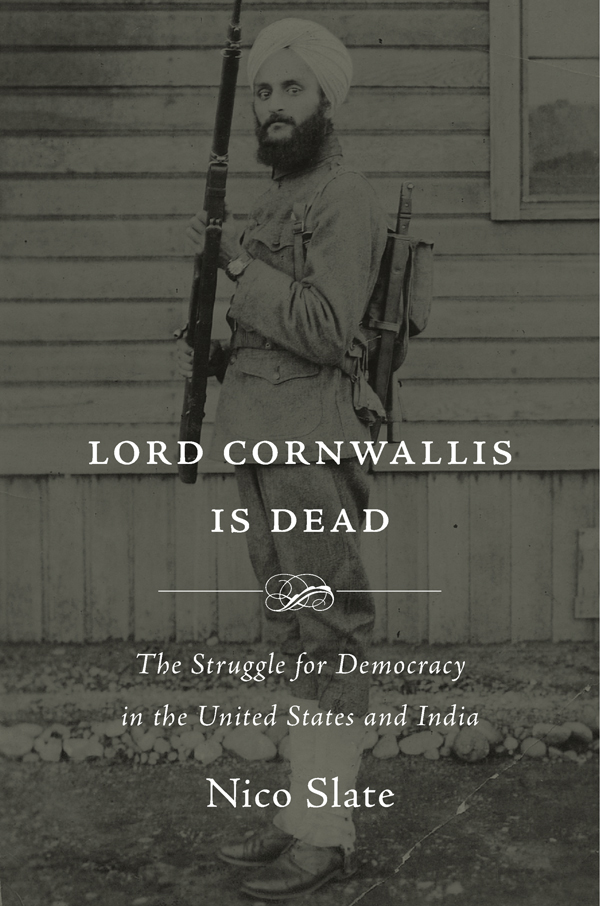

Jacket art: Bhagat Singh Thing. Courtesy of David Thind and the South Asian American Digital Archive.

978-0-674-98344-1 (alk. paper)

978-0-674-98915-3 (EPUB)

978-0-674-98916-0 (MOBI)

978-0-674-98917-7 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Slate, Nico, author.

Title: Lord Cornwallis is dead : the struggle for democracy in the

United States and India / Nico Slate.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018007627

Subjects: LCSH: DemocracyUnited States. | DemocracyIndia. |

IndiaCivilizationAmerican influences. |

United StatesCivilizationIndian influences.

Classification: LCC JC423 .G638 2019 | DDC 320.954dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018007627

OUTSIDE THE CITY of Ghazipur, an hour east of Varanasi, the tomb of Lord Charles Cornwallis overlooks the Ganges. A marble dome, seventy-five feet high and sixty feet in diameter, the Cornwallis mausoleum embodies the ambitions of the British Raj. While the Ganges swells and shrinks, the stone crypt holds firm. Cornwallis would be proud. As governor-general of British India from 1786 to 1793, Cornwallis oversaw the growth of one of historys greatest empires. In 1757, the Battle of Plassey had given the British a foothold on the subcontinent. Cornwallis transformed that foothold into an empire that was built to last. His most famous innovation, a new revenue system, was known as the permanent settlement. Cornwallis knew, however, that what seems permanent today may crumble tomorrow. He had, after all, come to India in defeat.

Five years before he arrived in India, Cornwallis lost one of the most momentous battles of the modern era. On October 19, 1781, over six thousand miles west of Ghazipur, a joint force of French and American troops, led by the rebel George Washington, defeated Cornwallis and his soldiers in the bustling port of Yorktown, Virginia. Cornwallis lost much more that day than Yorktown. By surrendering his troops, he guaranteed victory for the rebels. Thirteen British colonies would become the United States of America, and Cornwallis would be shipped home in disgrace. As if his defeat was not sufficiently humiliating, Cornwallis was captured by a French ship while on his way home.

The emergence of the United States, a nation dedicated to democracy, threatened the very idea of empire. The battle of Yorktown did not, however, mark the end of empire or even of the British Empire. The defeat of Cornwallis is better understood as a transition point between empires. Defeated in the New World, the British turned to conquer the Indian subcontinent. As one British Empire died, another was born. Lord Cornwallis embodied the death and resurrection of the British Empire. His journey from Yorktown to Ghazipur reveals that American freedom was, from its inception, bound up with Indian freedomor what might be called Indias enslavement.

The rise of the British Raj was not a simple tale of freedom overcome by tyranny. In India, the British did not encounter egalitarian democracies. They displaced older empires. Cornwallis extended British rule by defeating the great Tipu Sultan. Tipu declared he would rather live a day like a lion than a hundred years like a jackal, and he died on the ramparts of his city. His courage inspired later freedom fighters. But Tipu was no democrat. Like the Mughal emperors that ruled much of India, Tipu Sultan occupied the apex of a divided and unequal society.

As in India so in America, British imperialism was not the only impediment to freedom. What did American independence mean to the hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans living in the rebellious colonies? The Revolution did nothing to break their shackles. At the inception of American independence, it was the British who offered freedom to the enslaved. At the battle of Yorktown, many slaves fled across British lines. Some were turned away by Cornwallis. Others were re-enslaved in the British Caribbean. But many found their freedom with the help of the redcoats.

The story of India and America is a story of many freedoms and many slaveries. In 1920, the African American scholar W. E. B. Du Bois declared, Most men today cannot conceive of a freedom that does not involve somebodys slavery. Du Bois imagined an expansive freedom and then strove to achieve it on a global scale. He was not alone. Thousands of patriots in India and the Unites States struggled to make real the democracy of their dreams. They fought for a freedom that would stretch not only across the borders that divide India from America but also across the borders that divide Indians from Indians, and Americans from Americans.

Today, India and the United States are often celebrated as the worlds two largest democracies. They are also among the most diverse. One of the central arguments of this book is that diversity can enrich democracy by connecting local, national, and transnational social movements. The fragments of the nation can inspire freedom struggles that defy the borders of the nation. Yet neither Indians nor Americans have fully achieved their democratic ideals, and their diversity remains fraught with intolerance and inequality. Other large, diverse democracies bear equally bold aspirations and equally tragic flaws. Think of Brazil or South Africa. But the story of democracy in India and the United States is uniquely significant. While the United States remains the worlds most powerful democracy, Indiathe worlds most populous democracyis growing in wealth and influence. Together, the United States and India will play a predominant role in shaping the future of democracy.

This book traces the many bridgespolitical, economic, cultural, and intellectualthat have linked India and the United States. But this is not a simple tale of the triumph of connection over difference. Indeed, many of the connections at the heart of this book were misconnections defined by mistakes, misunderstanding, or self-centered efforts to appropriate the foreign for intellectual or material profit.

The relationship between India and America began with a mistake. Believing he had reached that fabled land of spices, Christopher Columbus named his new discovery India. Since 1492, India and America have been intertwined. Trade networks carried ice from Walden Pond to Calcutta and an elephant from Calcutta to New York. Transcendentalists corresponded with Indian thinkers. American missionaries flocked to India. Hindu gurus attracted crowds across America. Two hundred thousand American soldiers served in India during the Second World War. While Gandhian civil disobedience inspired the American civil rights movement, the Indian American community fought its own battle for civil rights. Often estranged during the Cold War, India and the United States became allies in its aftermath. From yoga to nuclear politics, and Hollywood to Bollywood, Indo-American relations have become increasingly important to both countriesand increasingly misunderstood.