Preface and Acknowledgments

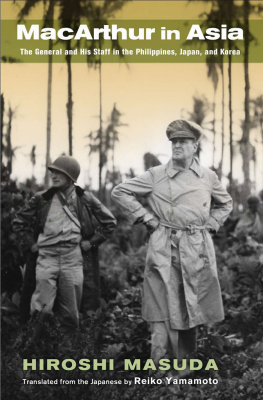

The enduring mythology around the figure of Douglas MacArthur (18801964) has been sustained in both the United States and Japan. Even a half century after his death, interest in and enthusiasm for MacArthur continue to grow. More than seventy books on MacArthur have appeared in the United States. In contrast, Japanese scholars have written only a few academic studies of MacArthur, although many translations of foreign studies as well as magazine articles have been published. Sodei Rinjiros Makkasahs Nisennichi (MacArthurs 2,000 Days), published in 1974, was the first major Japanese study of MacArthur. This book follows Sodeis, nearly forty years later.

American and Japanese accounts of MacArthur differ in their interests and focus. U.S. studies of MacArthur usually cover the eighty-four years of his life, including his relationship with his family, World War I, his period of service as Army chief of staff, his time as the military advisor in the Philippines, the war between the United States and Japan, the occupation of Japan, and his dismissal during the Korean War. They tend to treat MacArthurs activities in each period evenly and in detail. In brief, the intellectual interest in and the evaluation of MacArthur in his homeland focus not only on his distinguished talent for strategy and extraordinary courage as a commander in dangerous battlefields, but also on his distinguished leadership as a peacetime administrator. He has won respect and credibility as one of the greatest heroes of the twentieth century, who led his nation to a glorious victory.

By contrast, Japanese analysts are likely to concentrate on the five-and-a-half years of the Allied Occupation, the two thousand days when MacArthur administered Japan as the supreme commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP). MacArthurs dignity and authority surpassed those of Showa Emperor Hirohito, and his godlike presence at the peak of General Headquarters (GHQ) awed the Japanese people into silence. As supreme commander MacArthur carried out large-scale and essentially experimental reforms based on the Potsdam Declaration in order to rehabilitate Japan, transforming it from a military state into a democratic and peaceful nation. These reforms covered the Japanese legal system, politics, military affairs, the economy, social affairs, and the educational system, and included specific measures such as the drafting of a new constitution, the dismantling of the Zaibatsu, land reforms, public purges, the organization of labor unions, and the introduction of womens suffrage. Since so many elements of modern Japanese identity originate in the Occupation era, it is undeniable that MacArthur made hugely significant contributions as an administrator. Its a perfectly reasonable assumption that the Japanese Occupation would have been completely different had the supreme commander not been MacArthur. It can be safely said that the occupation of Japan was a MacArthur occupation. The differences in intellectual concerns between U.S. and Japanese accounts of MacArthur reflect the differences in historical experience between the two nations.

Two characteristics of this book should be noted. The first is that it begins not with the occupation of Japan, which is the focus for most Japanese studies, but with MacArthurs service in the Philippines, starting in 1935, ten years prior to the Japanese defeat. The reason for beginning in the Philippines is that MacArthurs experience there constitutes the origins of the Occupation policies he adopted in Japan. Using this longer perspective, the book clarifies parts of the Japanese Occupation that have not been fully explored in previous studies of MacArthur in Japan.

MacArthur had long and close ties with the Philippines, and he developed a deep affection for the Philippine people. Because his father had served as com mander of the army of the Philippines in the early twentieth century, Mac-Arthur chose the Philippines for his initial service (as a second lieutenant) after his graduation from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Following World War I, he was sent to the Philippines as commander of the Philippine army (at the rank of colonel). From the late 1920s through the early 1930s, he served as field marshal of the Philippine army (as a major general) and U.S. Army chief of staff (as a general), and after retirement in 1935, at the request of President Emanuel L. Quezon he was named military advisor for the organization of the Philippine army. Until his retreat from the Philippines, in March 1942, Mac- Arthur spent more than thirteen years in the Philippines, serving four tours of duty there. During his service he faced the Japanese military threat and the Japa nese invasion of the Philippines. He took as his vital mission the tasks of eliminating the pressure exerted by the Japanese southward advance and figuring out how to defend the Philippines once the Japanese invasion had begun.

Shocked by the surprise attack on Clark Field on December 7, 1941, which occurred almost simultaneously with the air raid on Pearl Harbor, MacArthur and his staff abandoned Manila and moved to Corregidor Island, a fortress in Manila Bay. His aim was to hold on to a military base and put up tenacious resistance on the Bataan Peninsula. Against a ferocious attack by some fifty thousand Japanese troops, the eighty-thousand-strong U.S.-Philippine defending force on the Bataan Peninsula was almost overwhelmed. Following orders from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, MacArthur and a few of his staff managed to break through the Japanese siege and escape from Corregidor to Mindanao and on to Australia. Although this dramatic evacuation strengthened the hero myth of MacArthur, he had deserted his men at the most critical moment of their hopeless fighta blow to MacArthurs pride that became, for him, the greatest dishonor of his life. His famous phrase I shall return! made in a speech to news reporters at the Adelaide railway station in March 1942 while on his way to Melbourne reflected the self-reproach caused by this experience.

Nevertheless this mortification contributed to a firm resolution. MacArthur became determined to avenge his humiliation by attacking the Japanese and completely defeating them as a military power. It was a determination that stemmed not simply from his responsibility as a commander but also from a desire to wipe away his disgrace. Launching a counterattack from Australia and fighting through the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, and Morotai Island, Mac-Arthurs troops successfully landed on Leyte Island in the Philippines in October 1944. He thus fulfilled his I shall return pledge. After difficult fighting and many casualties , MacArthur recaptured Manila from the Japanese in March 1945. MacArthur implemented a series of policies for the demilitarization and democratization of the Philippines, including military reforms, administrative reforms, arrests of war criminals and public purges, construction work, and health and welfare policies.

The reforms that MacArthur carried out in the Philippines provided a template for those he would later implement during the occupation of Japan. In effect, Manila was a proving ground for what was later accomplished in Tokyo. It is, therefore, indispensable to examine the Philippine period in order to understand the occupation of Japan.