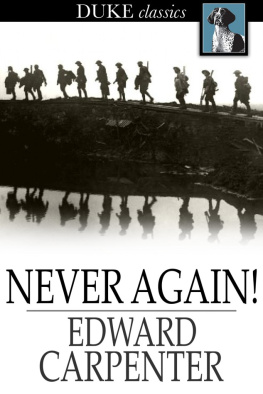

First published in 1917

by George Allen & Unwin Ltd

This edition first published in 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1917 George Allen & Unwin Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under LC control number: 17031568

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-18392-6 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-315-64551-3 (ebk)

I

Introductory

Although the following papers were mostly written before the Great War broke out, yet it will be noticed that the consciousness runs through them of a great impending crisis and transformation of our social arrangements, both in this country and in Western Europe. It may not have been clear at that time exactly how that crisis would come about; but now that the War is on us we can see how inevitable in a sense it has been, and how this deadly strife of nations has flowed (in the main) from the hopeless falsity of the social and industrial conditions prevailing in the countries concernedthe falsity of undemocratic societies divided into classes whose chief object in life was to prey upon each other; the falsity of a so-called social order which ignored the rights of women ; and the falsity of an industrial system whose real object was not public welfare but private gain, not the production of goods for use but the exploitation of labor for profit. Robbery and strife, more or less covered over and concealed by canting phrases, have eaten deep into the heart of these nations, and that over a long period ; and now at last we see that it was inevitable that some time this spirit of enmity and inhumanity, this internal disease, which has for so long afflicted us, should break forth and come to the surface, if even in the thunder of guns and the drenching of Europe with blood.

In a way the fact that some of these causes of disaster were traced and exposed (as they were by many Socialist thinkers) long before the disaster itself arrived, gives their exposure additional validity and force. Whatever side-issues there may be in the present catastrophe, we cannot doubt that financial greed and profit mongering, made all the more possible by the domination of the profit-mongering classes, have been at the bottom of the trouble. The war began with the speculative plotting of Germany for the development of Mesopotamia and the Baghdad Railway, and now England is apparently showing her high moral disapproval of this by taking over the development herself 1 Whatever may be thought about individual and isolated instances, it is evident that commercial ambitions, and the consequent demand for the annexation of territory, have for long enough in all the nations concerned been leading up to a crisis of deadly conflict; and the connexion of this with class-domination is well illustrated by the fact that Russia with the change of her Constitution has immediately repudiated the desire for annexation, while the Socialists of Germany and the other countries repudiate it also.

But the long foreground of this tragedy, and its deep and intimate genesis out of the very heart and habits of the various nations, must persuade us of something elsenamely that it is not destined to pass over very quickly; and that its results will be profounder, longer-enduring and more far-reaching than we have even yet dared to imagine. Guglielmo Ferrero, the Historian of Republican Rome, points out in a late article in II Secolo, the extraordinary shortsightedness of the views held about the present European situation by the politicians generally. " Great things," he says, "are maturing in the world. From one end to the other there is preparing the most gigantic trial or test (ordalia) that ever has been seen, of States, dynasties, nations, parties, religions and philosophical doctrines. It is like a universal Judgment day. Worldly crowns and powers, with their ancient glories, their idols, their altars and their faiths are apparently ready to roll in the dust"; and yet while the one living idea which can save society is that of a new social order resting on reason and on justice " there have so far only appeared on the scene, old men, professing old ideas, making use of old principles, repeating ancient discourses, and seeming to be willing to do anything rather than change their old habits of the courtier, the official, and the Parliamentarian."

I have no intention here of entering into political questions ; but certainly in the social and industrial field the limitation of outlook among our British leaders is little short of astonishing. In all the talk lately about the renovation of the country after the war, about the finding of employment for returning soldiers, the planting of the people on the land or in industrial life, and so forth, it seems to be taken for granted that when things settle down again, our general industrial system will return as before: that "employers" will once more "find work" for their men, that the "employed" will be only too thankful to escape from prowling the streets; and that (of course) nothing will be produced unless it yields a "profit" to some onea dividend to a shareholder or a rent to a landlord. There seems to be no suspicion of the possibility of any other arrangementor if there are suspicions they are indeed kept dark!

Similarly with regard to our foreign trade, great caucuses and conferences are being held with the object of diverting trade from its natural channels in such a way as to benefit ourselves and do despite to our "enemies." It is of course a case of trying to make water run uphill. Yet there seems to be no foresight of the fact that with the growing internationalisation of world traffic (not to mention the growing internationalisation of the peoples themselves) such schemes are doomed to failure, or at most to a very short-lived success.