Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright 2000 by The University Press of Kentucky

Paperback edition 2005

The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-9135-5 (pbk: acid-free paper)

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of American University Presses |

To the Memories of my Grandparents:

James Henry Toner (18841914)

Ethel Mathews Toner Aldrich (18911943)

Joseph John Leahy (18711954)

Ellen Cotter Leahy (18771950)

for the life you gave

for the example you set

for the heritage you created

CCC#958

2 Macc. 12:4346

Job 19:25

The worst temptation for mankind, in the epochs of dark night and universal perturbation, is to give up Moral Reason. Reason must never abdicate. The task of ethics is humble but it is also magnanimous in carrying the mutable application of immutable moral principles even in the midst of the agonies of an unhappy world, as far as there is in it a gleam of humanity.

Jacques Maritain (18821973)

Preface

I like prefaces. I read them. Sometimes I do not read any further.

Malcolm Lowry

If you think about what you ought to do for other people, your character will take care of itself.

Woodrow Wilson

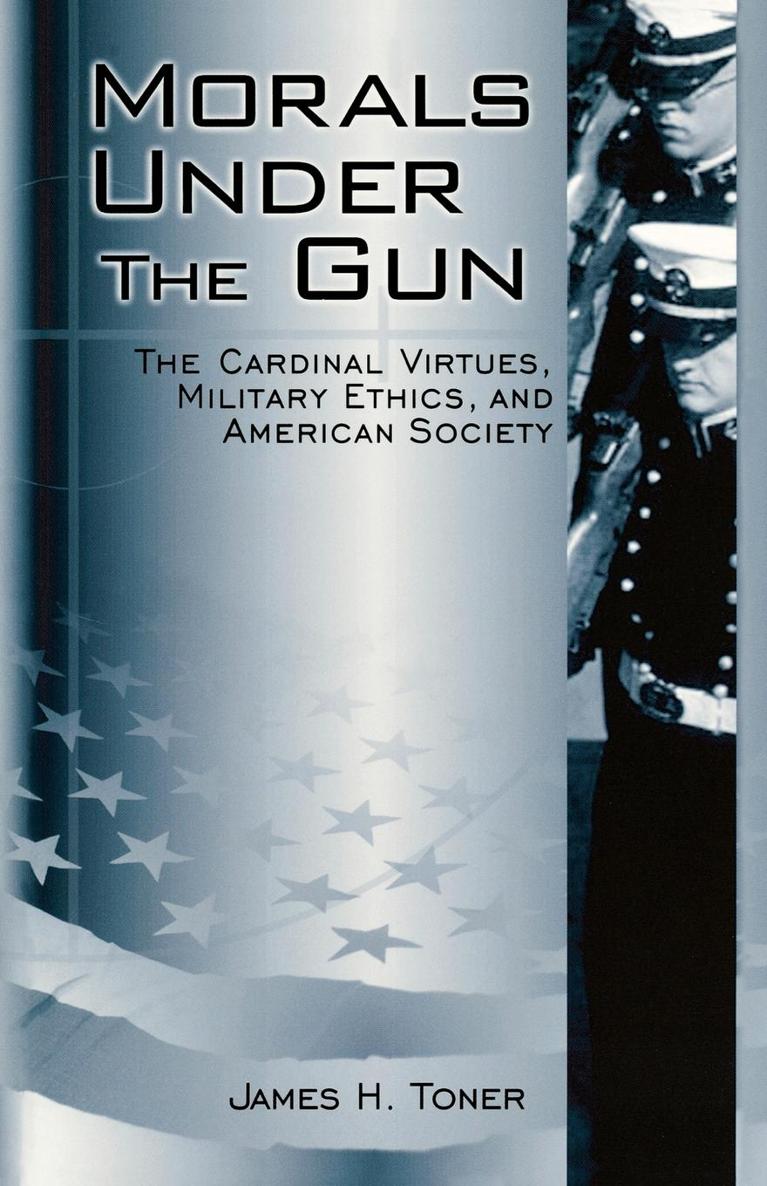

I want my readers to read this prefaceand more. So, in an effort to attract and keep your interest, I will tell you at once what Morals under the Gun is all about. My argument is, at its heart, very simple: moral life in America is out of order to a considerable extent.

So this is a book about connections. Theological ethics and philosophy have much to teach usthe concept that justice is superior to law is only one example of that. We civilians have much to teach the armed forcesthe concept of civilian control of the armed forces is only one example of that. The armed forces have much to teach us, their civilian superiorsthe concept of sacrifice is only one example of that. Civilians and soldiers alike must never again forget the macroethical lessons of the just war and the microethical lessons of being good, kind, and decent human beings. That takes us back to Wilson, to King, and to religion: concern for others. That is one reason this book ends with a chapter on character.

A PECULIAR ASSORTMENT

A glance at the bibliography, a list of the articles and books to which I owe the inspiration for this work, will confuse any interested reader. It is an odd assortment, this bibliography. There are military books such as The Downsized Warrior, by McCormick, and Dereliction of Duty, by McMaster. There are international geopolitical books such as The Grand Chessboard, by Brzezinski, and The Clash of Civilizations, by Huntington. This is sensible because, after all, I do teach at a war college run by the U.S. Air Force. But there are also books by such Christian writers as Servais Pinckaers and Norman Geisler, evangelist Josh McDowell, and apologists Peter Kreeft and C.S. Lewis. There are some of the great works of philosophy by Plato and Aristotle. There are a number of books about classical education, such as Who Killed Homer? and Cultivating Humanity; about writing and fiction, such as Flannery OConnors The Habit of Being and David Denbys Great Books; and about contemporary American life, such as For Shame and One Nation after All. A cursory glance at the bibliography signifies what I try to do hereconnect ethics and moral theology with the profession of arms.

I have explained already that this book is about the U.S. armed forces. But it is not that simple. I am now in my tenth year of teaching ethics at the Air War College at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama. Before coming to the War College, I taught at a military college for thirteen years. Before that, for a year I taught international politics to Naval ROTC midshipmen at Notre Dame. Before that I was an army infantry officer whose only real achievement in four years of active duty was earning my parachute badge. I joined the army on 14 May 1968, my birthday; although I was honorably discharged six years later, I have been around the U.S. military now for more than thirty years.

I am not a soldier, sailor, airman, marine, or Coast Guardsman, but I have written for, lectured to, and otherwise been involved with educational programs with all five services. In talking principally about contemporary ethics with members of the five services, I have discovered that soldiers (I use the term generically) find most philosophy too convoluted and abstract to have a serious impact on their world. I do not mean this in a negative or pejorative way. Consider the average army captain, whose pace of operations today is often extremely busy. As a professor, I hope he finds time to read. When he does, he is likely to read books related to his military specialty and, perhaps, a book or two about an area of the world to which he may be assigned. Can you reasonably blame him for not plowing through The Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle? Should he read Kant? Saint Thomas Aquinas? John Stuart Mill? Sartre? The fact is that most soldiers know smatterings of philosophy and theology, butunderstandablythey have rarely thought about philosophy systematically. Moreover, many, if not most, military chaplains, as busy as they are with pastoral concerns, find little time for review of theological ethics, which they may not even have studied years before in seminary. There are, in short, too many soldiers ignorant of philosophy.

BRIDGING GAPS

I have also been appalled over the years to discover that only a handful of our countrys colleges seem to have even the foggiest notions of what military ethics is all about. Very recently, I had an E-mail exchange with the administration of a large university in Nebraska, initially asking a question about a chair in military ethics. The question was referred to an army captain in ROTC who patiently explained to me, via E-mail, how army ROTC is conducted on the campus. That the idea of a chair in military ethics was lost on the captain, I could understand. That the university administration seemed, at least at first, not even to understand the idea was, however, more typical than one would customarily think. Many colleges teach philosophy courses along the idea of just war. But when problems such as Tailhook, the Flinn case, the Lavelle affair, and the like occur, philosophy instructors who may not know the difference between an M16 and an F-16 are understandably puzzled by the military ethos. There are, in short, too many philosophers ignorant of military affairs.