First published 1981 in Great Britain by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

Transferred to Digital Printing 2006

This Collection Copyright 1981 Routledge

ISBN 0 7146 3182 5 (Case)

ISBN 0 7146 3181 7 (Paper)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Routledge and Company Limited.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent

Song of Nigeria

Lord we beseech your help

To guard us from the iniquities of the world.

Let our country grow and be known

All over this broad earth.

Let everyone prosper in it

Without fear and without persecution.

Help our land find honour,

Place her on the path of truth.

Help her develop and become renowned

Let her be an example to Africa.

Let her prosper, let there be wealth

Everywhere in Nigeria

So that we all will be people to be proud

That we are living in Nigeria

And thank God

That he placed us among the people of Nigeria.

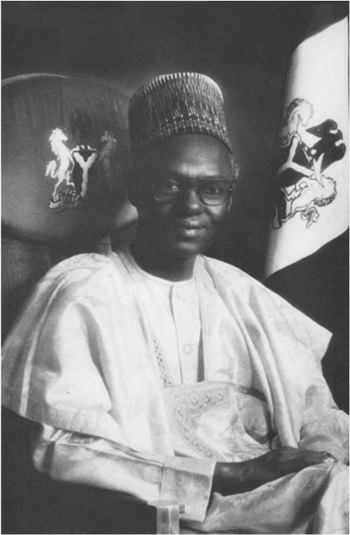

The last verses from a 500 verse poem, Wakar Nigeriya, or The Song of Nigeria, originally written, in Hausa, by Alhaji Shehu Shagari in 1948, when he was a teacher at Sokoto Middle School, as a textbook to tell children about their country. For years handwritten copies were used in schools throughout Hausa-speaking areas. In 1972, when he was Federal Commissioner of Finance, he was invited to prepare a new edition by the Northern Nigerian Publishing Company, Zaria. Published the following year, this made him better known in many areas than all his political career. The translation is by David Hofstad and Ibrahim Umaru of the Hausa Language Service of Voice of America. A musical arrangement of some of the verses was sung at the White House banquet given by Mr Carter for the Nigerian leader during his one-day State Visit to Washington in November, 1980.

Introduction

NIGERIAS RETURN to democratic civilian rule on October 1, 1979, after thirteen and a half years of military government, changed the political face of West Africa. The worlds ninth most populous country and third biggest democracy, Nigeria has some 80 million people, well over half the total population of West Africa. UN projections give her a population of 153 million by the year 2000; they suggest that at some time in the 21st century she will become third country in the world in population. And today she is among the worlds six most important oil exporters.

The attachment to democracy of such a people and their success in working its institutions is of the highest significance for all mankind. The responsibility for such success now rests largely with the 56-year-old former headmaster who was elected Nigerias first executive President in the countrywide elections of 1979, Alhaji Shehu Aliyu Shagari. In the words of the framers of the American-type constitution under which Nigeria returned to civilian rule, the President, elected by the people as a whole, is expected to be, whatever his party, the clear focal point for national loyalty.

The selection from the Presidents speeches and writings which follows covers only the first eighteen months of his four-year term of office. But they also look far forward. They include, for example, his speech on the 198185 Development Plan under which capital spending of some 70 billion in the public, and 12 billion in the private, sector is envisaged (the Naira, introduced in independent Nigeria to replace the Nigerian pound, is worth 0.79). His declarations on external affairs, notably on Nigerias determination to secure the eradication of apartheid and to further economic co-operation in Africa, also represent abiding policies. And his views on public morality, on religion, on the pre-eminent importance of agriculture, the role of the armed forces, the nature of Nigerias Presidency and constitution, the work of civil servants and many other aspects of Nigerias public and social life, will not change.

The speeches also reveal, however, the vastness of the problems with which Alhaji Shehus Administration is grappling; some are short-term, some are born of the nature of the country itself. For Nigeria matches India in complexity. Her people use some ten major and hundreds of lesser languages, together with English as an official language. Her frontiers were created by Europeans less than a century ago. They enclose ancient kingdoms such as Benin, Kano, Ife and Opobo; and communities, too, of only a few thousands who traditionally recognised no wider allegiance. Some traditional chiefs, who no longer play an active role in administration, today represent communities of millions; some only of hundreds. Some so-called tribes ethnic groups, if clumsy, is a better term are large enough to deserve the title nation: others comprise little more than a collection of villages.

Nigerias national political institutions are entirely new, but there is abundant evidence of high culture thousands of years ago. Half the people, and most of those of the Presidents own state of Sokoto, are Muslim; a high proportion of the rest Christian. Followers of these faiths live and work at peace with each other and with those who adhere to traditional religions. Nigeria is perhaps the worlds most conspicuous example of such religious harmony. Those who saw in the two and a half year civil war evidence of religious fanaticism know nothing of the issues or the contestants. Yet at the end of 1980 the great northern city of Kano experienced murderous disturbances arising out of such fanaticism but of a spurious Muslim sect directed against the citys Islamic people.

Although respected by Nigerians of all political persuasions, religions, and ethnic groups, and secure for his four-year term, Alhaji Shehu has to show great political skill to secure support for his measures. Although over 47 million people over 18 registered to vote women in some areas for the first time only about a quarter voted in the first four stages of this vastly complicated election, and about a third in the poll for the President. Of these the President, while gaining the highest vote, did not secure a majority. Nor did his party, the new National Party of Nigeria, NPN, win a controlling majority over the other four in either house of the National Assembly; and it governs only seven of the nineteen states, over whose Governors he has only the most indirect control.

So he and his lieutenants have constantly to rely on alliances, however temporary, to ensure the acceptance of his measures, even budgets, in the National Assembly he scored a notable success in getting his Revenue Allocation Bill through an apparently hostile legislature. He has to ensure that ethnic feeling, which had had some effect on the election results, is controlled and that people from all parts of the federation participate fully in his national administration. He inherited a weak bureaucracy at all levels of administration, and public services strained by the expansion and the demands of an expanding economy, to which oil revenues gave immense strength, while also producing serious inflation. Agriculture was stagnant, and food prices were rising dangerously. Violent crime was widespread. The trades unions, after years of military restrictions, were expected to be anxious to try their strength under more liberal conditions.