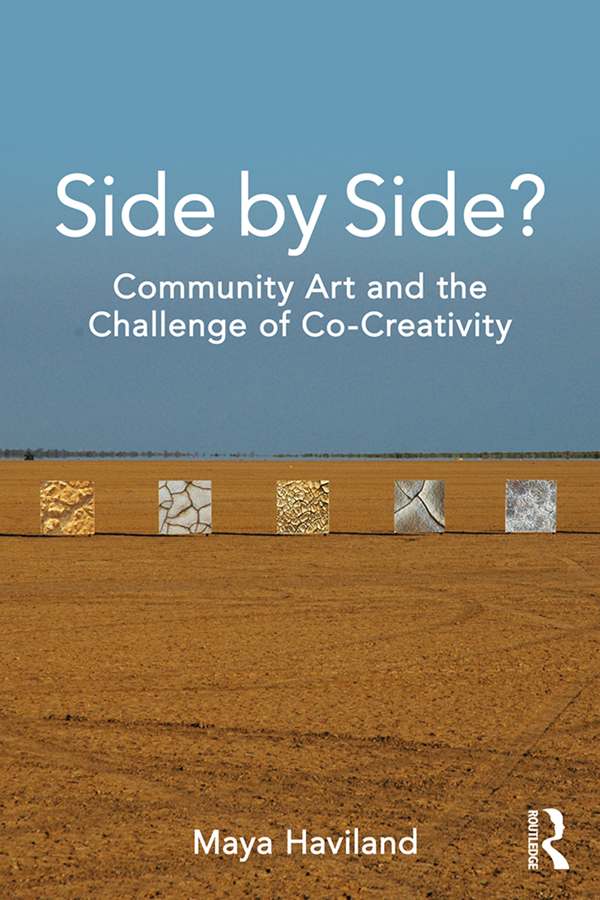

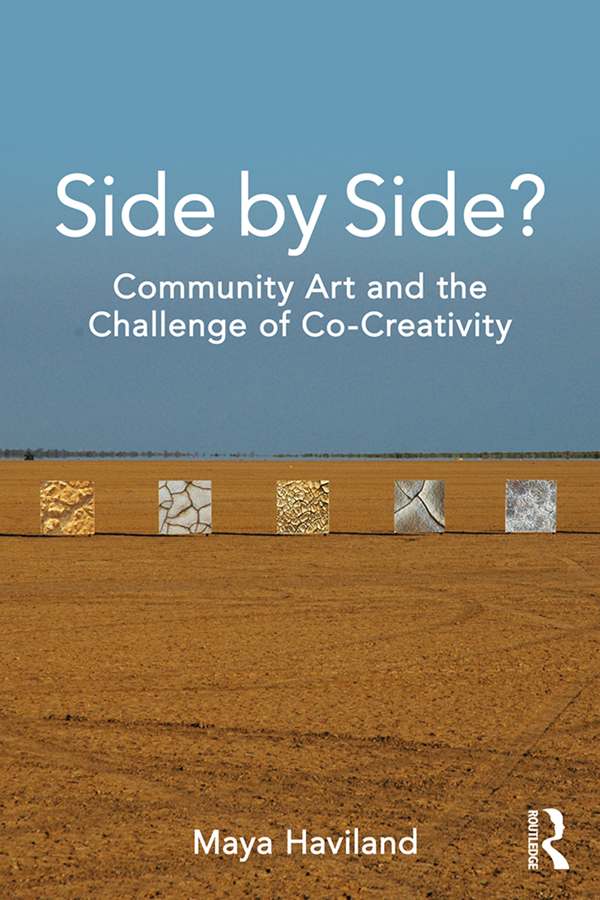

Side by Side?

A new wave of community arts projects has opened up exciting areas of cross-cultural creativity in recent years. These collaborations of local people, arts facilitators, anthropologists and supporting organisations represent a flourishing new form of arts-based collaborative anthropology that aims to document the stories and cultures of local people using creative art forms. Often focusing on social and cultural agendas, from education and health promotion to advocacy and cultural heritage preservation, participants bring together methods historically linked to anthropology with those from the arts and community development.

Side by Side? Community Art and the Challenge of Co-Creativity investigates these creative projects as sites of significant cultural creation and potential social change. Through the exploration of a range of diverse collaborations, the common threads and historical contexts in this domain of cultural creativity are examined. The role that creative arts collaborations can have in disrupting existing hierarchies of social power and knowledge creation is analysed, as are the potential futures, historical and cultural implications of these co-creative practices.

Drawing on the experiences and reflections of over 30 facilitators from more than 7 countries, and written by an experienced collaborative arts practitioner and researcher, this exciting book will play a defining role in the emerging critical discourse on collaborative art and collaborative anthropology. It is essential reading for collaborative anthropologists, arts facilitators and others who aim to collaborate cross-culturally, as well as students of art, anthropology, and related subjects.

Maya Haviland is an artist, community facilitator and researcher. She is Lecturer in Museum Anthropology at the Centre for Heritage and Museum Studies in the School of Archaeology and Anthropology at the Australian National University, an Adjunct Research Fellow at the Nulungu Research Institute at the University of Notre Dame Australia, and a Professional Associate at the Centre for Creative and Cultural Research at the University of Canberra. Her research focuses on co-creativity, cultural and organizational development and dynamics of collaboration.

First published 2017

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

and by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2017 M. Haviland

The right of Maya Haviland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Names: Haviland, Maya, author.

Title: Side by side? : community art and the challenge of co-creativity /

Maya Haviland.

Description: Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY : Routledge, 2017. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016025021 | ISBN 9781138219854

(hardback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781138219861 (pbk. : alk. paper) |

ISBN 9781315414416 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Artists and community. | Community arts projectsSocial

aspects. | Art and anthropology.

Classification: LCC NX180.A77 H38 2017 | DDC 700.1/03dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016025021

ISBN: 978-1-138-21985-4 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-21986-1 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-41441-6 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

Contents

This book would never have been written without the sustained support of Brad Riley, my beloved partner, fellow adventurer and co-parent. You have been with me from first conception to last edits, this achievement is yours as much as mine. Thanks also to my two sons, Aubrey and Leo, born during the journeys of research and writing; you have contributed valuable perspective and pacing to the tasks at hand. As Leo so wisely said, Now its time for reading.

Many people provided practical and other support to me throughout this projectcooked, cared for kids, read, commented, discussed, provided housing, vehicles, inspiration, guidance and friendship. These include Emma Carlin, James Clifford, Linda Connor, Marilena Crosato Madeleine Eron, Faye Ginsburg, Sophie Haviland, Steve Kinnane, Inge Kral, Luke Eric Lassiter, Nigel Lendon, Howard Morphy and James Pillsbury to name but a few. Special thanks to my mother Leslie Devereaux and father John Haviland for your practical assistance, spiritual and intellectual support; to Rachel Breunlinfriend, colleague, and inspirationyour work has provided a backbone to my research and has deeply influenced my own creative practices; to Carlota Duarte and the women photographers from the Chiapas Photography Project for your generosity, sustained commitment and willingness to agree to disagree; and to all the people whose work features in this bookyour creativity and commitment is what it is all about. Any mistakes about the work of others in this text are my own. Thanks to the Australian government and the Australian National University for scholarships and grants that enabled the research from which this book has drawn.

Finally, thanks to our friends in Pango village and Port Vila, on Efate Island, VanuatuI can think of no better place to write than here on the edge of the Pacific Ocean with all of you.

Please note: this book contains the names and images of people now deceased.

My first knowledge of the Chiapas Photography Project (CPP) came during Christmas of 1998 when I was given the book Creencias , by Maruch Sntiz Gmez (1998). I was spending Christmas with my family in San Cristobal de Las Casas, in Chiapas, Mexico, where my father, his second wife Lourdes De Leon and my young sister were living. As a Christmas gift Lourdes gave me the book published by the sister project to the CPP, the Archivo Fotogrfico Indgena (AFI, indigenous photography archive). She told me a little about the two projects, in which indigenous people from in and around San Cristobal were supported to use photography to document their lives and cultures. I was immediately fascinated with the Creencias book, which was to become an internationally recognised work and a landmark in the emerging history of indigenous womens photography in Mexico. However it was not for this reason that I was initially intrigued by it.

I had grown up as a regular visitor to the highlands of Chiapas, the daughter of anthropologists whose work focussed on the languages, lives and cultures of people in Zinacantecan villages in that region. From when I was first beginning to walk I spent regular periods of time living with my family in the Zinacanteco (Zi) household of the Vasquezes. They live in the village of Navenchauc, about a half-hour drive from San Cristobal on the Pan American Highway. Before I was born, my father and mother had built a small cinder block house in the Vasquezes compound. As I was growing up we would live there for months at a time. Dads research, it seemed to me, involved long conversations about anything and everything: sitting by fires, in cornfields, at the market, talking, talking. Mum learned to weave, cook and pat tortillas like a Zi woman. Although I never learnt Tzotzil (the local Mayan language), I spent many hours sitting with the women of our household, Tzotzil conversation washing over me. While everyone talked I was playing with baby chickens and balls of homespun yarn or helping with chores such as moving the sheep from pasture to pen. Id help with bundling coriander for market and steal bites of uncooked maza from the corn bucket destined to become the warm tortillas I craved when we were back home in Canberra, Australia. The Zi culture I knew from my life in Navenchauc was a daily domestic one, lived on hardened mud floors. Life revolved around blackened clay pots bubbling with beans or coffee. Womens work consisted of weaving, spinning, drawing water, harvesting fruit and vegetables, grinding corn, patting tortillas, and peering from doorways to hear news passed from mouth to mouth down the narrow mud alleys of town.