First published in 2004 in Great Britain by

FRANK CASS PUBLISHERS

Crown House, 47 Chase Side, Southgate, London N14 5BP

and in the United States of America by

FRANK CASS PUBLISHERS

c/o ISBS, 920 NE 58th Street, Suite 300

Portland, Oregon 972133786

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005.

To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledges

collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.

Website www.frankcass.com

Copyright 2004 Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Neo-medievalism and civil wars

1. Sovereignty 2. Civil war 3. International relations

4. Intervention (International law) 5. World politics 1989.

I. Winn, Neil II. Civil wars.

320.1 5

ISBN 0-203-33049-8 Master e-book ISBN

ISBN 0 7146 5668 2 (Print Edition) (cloth)

ISBN 0 7146 8570 4 (paper)

ISSN 1369-8249

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Neo-medievalism and civil wars/editor, Neil Winn.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-7146-5668-2 (cloth)ISBN 0-7146-8570-4 (pbk.)

1. International relations-Philosophy. 2. National state. 3.

Political violence. 4. Terrorism. I. Winn, Neil. II. Title.

JZ1251.N46 2004

327.1 01dc22

2003022944

This group of studies first appeared in a Special Issue on

Neo-Medievalism and Civil Wars in Civil Wars 6/2 (Summer 2003)

published by Frank Cass (ISSN 1369-8249).

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher of this book.

Introduction: New Forms of Political Organisation, Community, Sovereignty and Identity: Civil Wars, the New Diplomacy and International Relations

NEIL WINN

Since 1989 the concept of civil war has taken on new salience in international relations. Significant inquiries into inter-ethnic violence emphasising studies of political community, identity, sovereignty, and political organisation have dominated the study of civil war in the past decade. Processes of social denationalisation of national identity have become more prevalent in everyday politics. Following Charles Tilly, civil violence is the product of three main influencing factors: coercive, capitalist and capitalised coercive.

Not only would this undo international society, but such a system would radically transform political life itself, returning it to something analogous to the medieval world: a lack of mutual recognition among entities, an absence of anarchy in the Waltzian neo-realist sense, and a more complex pattern of relationships to consider.

In order to understand modern forms of political organisation and cultures it is initially necessary to review more traditional forms to place the analysis in context. It was not until the eighteenth century that the term nation came to be used as the expression for the then emerging dominant form of identity and political organisation in post-revolutionary France and the wider Europe. Generally speaking, in the literature on culture and identity, the nation comprises a shared culture, shared history, delimited territory (a homeland) and common laws. Nations can be viewed as voluntaristic (that is, based on mans will to be part of the nation, shared cultural characteristics: loyalty; solidarity; identification) and/or forcedimpelled from the outside by an external threat (that is, forced by coercion and fear to be part of the nation).

Benedict Anderson, an anthropologist, argues that the nation is an imagined political community. Anderson labels sixteenth-century England as the first nation, with bonds of common national interests solidified by the monarchy and the role of the landlord. Since the late eighteenth century the processes of homogenisation, standardisation, and the associated emergence of human rights after the American and French revolutions (and the accompanying values of liberty, equality and fraternity) have been accompanied by the transmission of core values via education, the printed word, and so forth. In contrast to the nation, the state refers to the political organisation of societies (with a distinct set of political institutions) that displays sovereignty both within geographic borders and in relation to other sovereign entities.

The nation-state, in its modern form, is a sovereign entity that is normally dominated by a single predominant national culture. The nation-state is a mythical and intellectual construct with a highly persuasive and powerful political force. A world of nation-states implies an international system of pure sovereign states, relating to each other equally as equals. Nation and state combined creates an enormously compelling mixture of legitimacy and efficiency for governing elites and societies. The nation-state, in this view, has two big advantages.

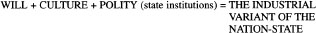

FIGURE 1

First, the authority of elites, as a natural embodiment of the identity and will of the citizens, creates a firm base for legitimate government.

Second, in addition, peoples who are secure economically and culturally behind their own borders, can negotiate with each other fairly and amicably.

The modern nation-state can be represented as follows:

However, what preceded the modern nation-state in Europe? Does this debate have any relevance for contemporary European identity formation and organisation? What we might term Western medieval Europe lasted for about 1,000 years from the year 500 to about 1500, and was called Respublica Christiana. It was a universal society based on a joint structure of religious authority (sacerdotium) and political authority (regnum) which gave at least minimal unity and cohesion to Europeans whatever their language and homeland. The people had a customary political loyalty to their immediate feudal superiors, and only a weak loyalty to the King (the state). Instead, medieval Europeans had a strong obedience to the (Western) Church headed by the Pope.

The Thirty Years War (161848) was the last war where state or empire tried to impose/enlarge their empire to the rest of Europe in the name of Respublica Christiana. After 1648 the language of international justification changed towards international diversity based on a secular society of sovereign states. At the end of the Thirty Years War, the Treaty of Westphalia (1648) was signed. The Westphalian International Society was based on three principles: that the King is Emperor in his own realm; that the ruler determines the religion of his realm; and the balance of power, in order to prevent any hegemon from arising and dominating everybody else. Napoleon I of France was the first state leader to be subjected to the Westphalian model by a coalition of European powers, who formally assumed the status of great powers and proceeded to govern Europe by a Congress to prevent France establishing itself as a hegemonic power. Indeed, Napoleon I was the last leader to claim the title of Emperor, drawing on a heritage going back to Charlemagne and even further back to the Roman Caesars.