Newest Born of Nations

A Nation Divided: Studies in the Civil War Era

ORVILLE VERNON BURTON AND ELIZABETH R. VARON, Editors

Newest Born of Nations

European Nationalist Movements and the Making of the Confederacy

Ann L. Tucker

University of Virginia Press

Charlottesville and London

University of Virginia Press

2020 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2020

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tucker, Ann L., author.

Title: Newest born of nations : European nationalist movements and the making of the Confederacy / Ann L. Tucker.

Other titles: Nation divided.

Description: Charlottesville : University of Virginia Press, 2020. | Series: A nation divided : studies in the Civil War era | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019057959 (print) | LCCN 2019057960 (ebook) | ISBN 9780813944289 (cloth) | ISBN 9780813944296 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: NationalismConfederate States of AmericaHistory. | NationalismEuropeHistory19th century. | United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Causes. | Confederate States of AmericaHistory. | Southern StatesHistory17751865.

Classification: LCC E459 .T88 2020 (print) | LCC E459 (ebook) | DDC 973.7/13dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019057959

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019057960

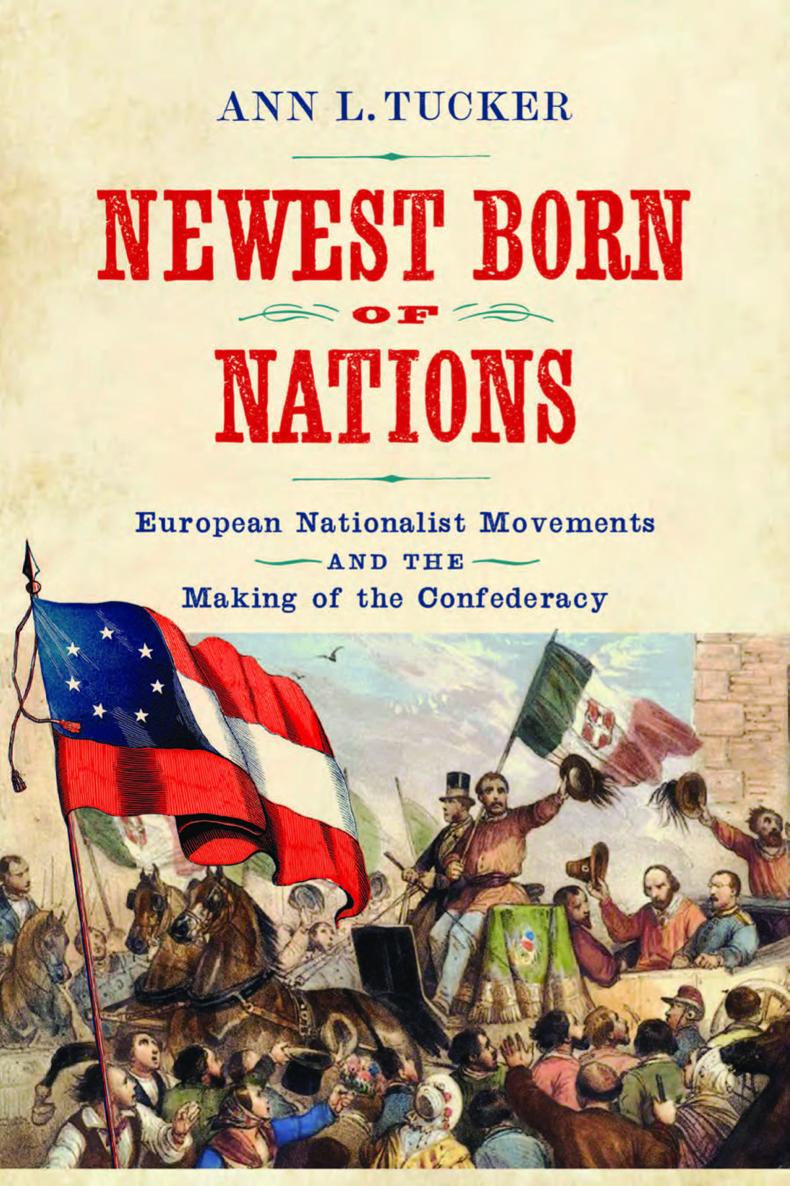

Cover art: Giuseppe Garibaldi enters Naples on 7 September 1860 (Pictorial Press Ltd./Alamy Stock Photo)

For my family

Contents

This work has moved with me through many chapters of my life, from graduate student to assistant professor, through multiple new jobs, and across the Southeast in a series of interstate moves. At each of these stages, I was fortunate to receive support and assistance without which this book would not be possible. I want to thank everyone who helped me with and through this project.

This book would not be what it is without the guidance of Don Doyle, who patiently helped me take a few unformed ideas and turn them into something meaningful, who provided countless suggestions for fruitful avenues of inquiry, who helped me clarify the parameters of the project and the ideas within, and who helped me parlay this work into a career.

This work also benefited from the mentorship of many other scholars who have been generous with their time and assistance. My professors at the University of Alabama and the University of South Carolina helped me develop the knowledge and skills of a historian. In particular, my committee members Thomas Brown, Lacy Ford, and Paul Quigley helped refine my ideas and set me on the path to this finished book. My fellow graduate students also provided helpful advice and insight as I was shaping this project.

As this project developed from idea to research to manuscript, many friends and colleagues have read portions of this work and shared their thoughts and suggestions. In particular, colleagues and graduate students at the University of Mississippi read and provided critical feedback on the newer portions of this work. My department and administration at the University of North Georgia, led by Jeff Pardue, have also been immensely supportive of this project, providing the support I needed to finish it. Additionally, friends and colleagues Kari Frederickson, Vernon Burton, Amy Fluker, Charles Eagles, Michael Woods, David Prior, Thomas Scarritt, Beatrice Burton, and Kathryn Tucker have provided significant support for this work or my career.

The earliest ideas for this project originated when I studied abroad in Venice, Italy, while an undergraduate at Wake Forest; I immediately fell in love with Italy and knew I wanted to study connections between Italy and the South. Such an opportunity would not have been possible without the help of Thomas Phillips and Randal Hall, then scholarship directors at Wake Forest, who mentored me through my undergraduate career and early historical research.

The University of Virginia Press, especially Dick Holway, have been endlessly patient as this project has spanned perhaps more stages and years of my life than we had initially anticipated. Knowing that my editors wanted a good book rather than a fast book enabled me to write a better book. I also appreciate the assistance of everyone at the press who worked with me on this project and helped turn the manuscript into the final product. The readers selected by the press provided insightful and useful feedback in their reports that helped me strengthen this work. I also want to thank Beatrice Burton and Margaret Hogan for their invaluable help and work with indexing and copyediting.

Beyond my professional life, friends at every step along the way have also supported me and helped make this work possible.

Most of all, however, none of this would be possible without my family. My love of history comes from my family, from my grandparents to my parents to my siblings. My family showed me how fascinating history can be, happily discuss and debate history with me, and have always supported and continue to support me and my interests. My sister Elizabeth, joined by my brother-in-law, Andrew, have helped me keep perspective on this work and life. My sister Kathryn has lived every step of this project, and of my larger career, with me. She has been an invaluable resource, both in providing the critical insight and knowledge of another historian and in being there with me through my journey. My parents, Mike and Diane Tucker, have supported me in countless ways, both small and enormous, through this project, through my career, and through my life; I could not have completed this work without them. Every scholar needs someone to help them relax and recharge, think through tricky ideas, support them through the inevitable hard places, and celebrate their successes, and my family has done this and so much more for me.

Newest Born of Nations

In the spring of 1861, as questions of nationhood consumed the United States, southern and northern minds alike turned to an unexpected figure. Giuseppe Garibaldi, a prominent Italian nationalist who had led a military expedition to help achieve Italian unification in 1860 and who had previously earned fame in the 1840s fighting for the cause of national independence in South America and Italy, presented the world with an example of a seemingly ideal nationalist. To Americans, struggling to answer many of the same questions of governance, rights, and self-determination that had fueled nationalist movements throughout the Atlantic world in the nineteenth century, Garibaldi presented possible answers. White southerners who sought to legitimize the new nation they were creating hoped that self-comparisons with Garibaldi and his nationalism strengthened their case for independent nationhood. As these beliefs in Americans ideological connections to Garibaldi reveal, both sides in the American Civil War conceived of their national mission as part of the broader international debate over proper expressions of nationhood.

Indeed, as demonstrated by Garibaldi and his international career and appeal, the first half of the nineteenth century appeared full of new possibilities and questions for supporters of aspiring nations around the globe, not just for white southern nationalists. Led by the Enlightenment-inspired American and French Revolutions, and driven by attempts to decolonize the Americas and to dismantle the European system of power established by the Congress of Vienna, an age of revolution saw potential nationalities throughout Europe and the Americas rising up and attempting to form independent nations out of multinational empires. A desire for national self-determination and self-government tied these revolutions together, and participants and observers alike recognized these ties. The goal of national liberty, however, did not resolve the troubling questions of how best to enact a program of self-government or how to build an independent nation, much less of who should be able to participate in these processes. Nor did even the loftiest of goals guarantee success, with more European nationalist movements failing than succeeding in the first half of the nineteenth century. Nonetheless, the promise of national independence proved so enticing that in February 1861, white southern nationalists in seven southern states, later joined by four more, met to declare themselves the Confederate States of America, a new nation, soon, they planned, to be welcomed as an equal in the international community of nations. For the elite white southern men who created the Confederacy, an international vision of the aspiring southern nation as one of many new nations seeking membership in the family of nations was central to their national self-conception.