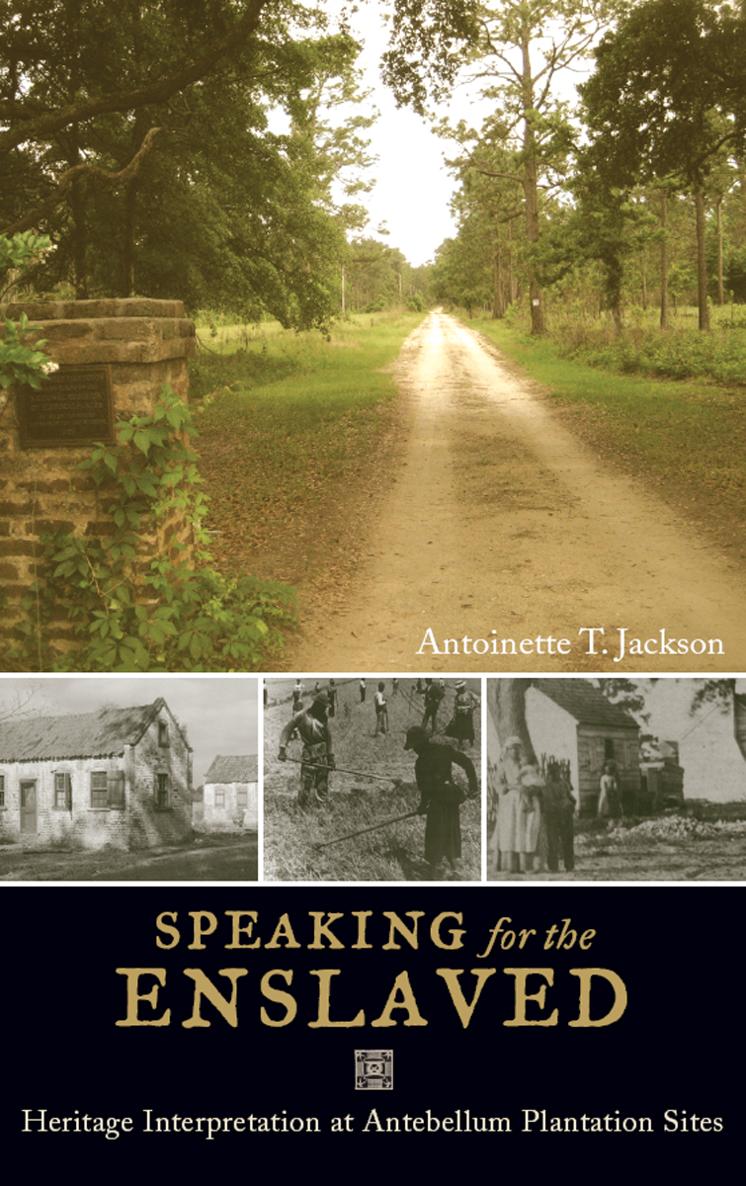

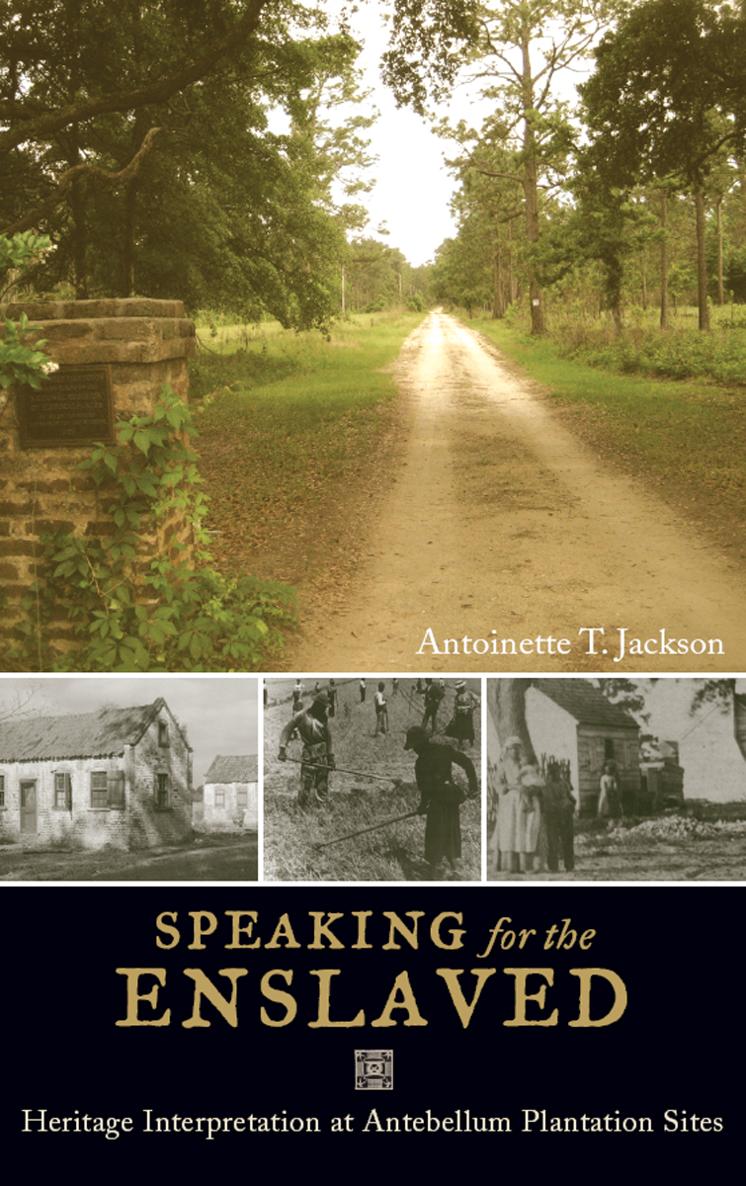

SPEAKING FOR THE ENSLAVED

HERITAGE, TOURISM, AND COMMUNITY

Series Editor: Helaine Silverman

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Heritage, Tourism, and Community is an innovative new book series that seeks to address these interconnected issues from multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary perspectives. Manuscripts are sought that address heritage and tourism and their relationships to local community, economic development, regional ecology, heritage conservation and preservation, and related indigenous, regional, and national political and cultural issues. Manuscripts, proposals, and letters of inquiry should be submitted to helaine@uiuc.edu.

Speaking for the Enslaved: Heritage Interpretation at Antebellum Plantation Sites, Antoinette T. Jackson

Heritage That Hurts: Tourists in the Memoryscapes of September 11, Joy Sather-Wagstaff

Inconvenient Heritage: Erasure and Global Tourism in Luang Prabang, Lynne Dearborn and John C. Stallmeyer

Coach Fellas: Heritage and Tourism in Ireland, Kelli Ann Costa

The Tourists Gaze, The Cretans Glance: Archaeology and Tourism on a Greek Island, Philip Duke

SPEAKING FOR THE ENSLAVED

Heritage Interpretation at Antebellum Plantation Sites

Antoinette T. Jackson

First published 2012 by Left Coast Press, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2012 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Jackson, Antoinette T.

Speaking for the enslaved : heritage interpretation at antebellum plantation sites / Antoinette T. Jackson.

p. cm. (Heritage, tourism, and community)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59874-548-1 (hbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-59874-549-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-59874-550-4 (institutional ebook) ISBN 978-1-61132-618-5 (consumer ebook)

1. Historic sitesInterpretive programsSouthern States. 2. PlantationsSouthern States. 3. African AmericansSouthern StatesSocial life and customs. 4. Plantation lifeSouthern StatesHistory. 5. Community lifeSouthern StatesHistory. 6. Material cultureSouthern StatesHistory. 7. Southern StatesAntiquities. 8. Public historySocial aspectsSouthern States. 9. MemorySocial aspectsSouthern States. 10. Southern StatesCultural policy. I. Title.

F210.J33 2012

975dc23

2012000882

ISBN 978-1-59874-548-1 hardback

ISBN 978-1-59874-549-8 paperback

For my ancestors

For making a way

by Paul A. Shackel

T he interpretation and inclusion of subaltern groups into the national public memory is often contested, and Antoinette Jackson in her finely crafted book, Speaking for the Enslaved: Heritage Interpretation in Antebellum Plantation Sites, provides several case studies dealing with African-American representation in the southeastern United States. All too often narratives create simple dichotomies of the past that separate ethnic groups into distinctive, simple categories. For African Americans in the southeast, these categories at plantation sites usually include slaves in the antebellum era and sharecroppers in the postbellum era. Public tours and the literature distributed to visitors at these plantations usually focus on the life and struggles of the plantation owners, and any interpretations of African Americans usually receive only generic references to slavery. Jacksons work challenges these traditional narratives.

By examining the heritage preservation and interpretation at several nationally known sites, Jackson shows that the past is often much more complicated than what is presented to the public. Such places as Friendfield, Jehossee Island, and Snee Farm plantations in South Carolina, and Kingsley Plantation in Florida, are contested grounds where forgotten narratives are beginning to help to create a more inclusive past and present. Jackson uses these narratives from the descendant community to complicate the stories of the past in order to create a more inclusive heritage. From collected oral histories from African-American descendants of Jehossee Island, now part of a National Wildlife Refuge in South Carolina, she counters the dominant narrative of the black communityslaves in the antebellum era and sharecroppers in the postbellum era. The enslaved Africans were responsible for many aspects of rice production, including as field hands, engineers, sailors, cooks, midwives, teachers, and artisans. The omission of this more textured story is, I believe, a continuation of the racism that continues to exist todaya racism that is not necessarily overt but rather covert. It is a racism by omission.

Jackson notes that anthropologists are calling for the systematic unveiling and recovery of subjugated knowledges, which is an important and necessary step in any social science. However, I believe that another major issues is this: Who is subjugating the knowledge and why? The exclusion of people and their misrepresentation is a political act, and it is a process that helped to reinforce a narrative that allowed for a white hegemony in the present.

Changing the narrative is often a result of a significant national grass roots effort. In some instances, the change is truly political. In this book, Jackson notes that some places, such as the Charles Pinckney house, a National Park Service site, have broadened the narratives interpretation not only to commemorate a noted drafter of the U.S. Constitution and a fierce proponent of slavery but also to include the many unknown Africans who worked on and around the plantation house. This more inclusive approach developed at the turn of this century, and it is a product of the political pressure applied by Congressman Jesse Jackson, Jr. In 1998, Congressman Jackson encouraged the National Park Service to increase African-American representation at national parks. As a result, park managers held a conference titled Holding the High Ground. The document from the meeting explains that the National Park Service was telling the story at these places that has traditionally been biased racially and socioeconomically, since it told the story of only the literate and enfranchised. A number of national parks have addressed this issue of representation and enslavement, and the stories of African Americans are now part of many more national parks. However, even as we move into the second decade of the twenty-first century, not all parks have created more inclusive narratives that allow all people as part of our national public memory.