Published by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

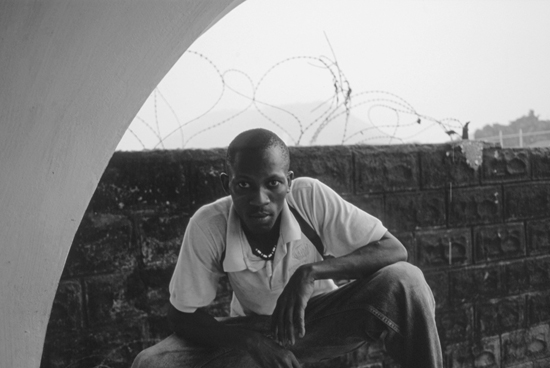

2015 by Marc Sommers

Photographs 2015 by Marc Sommers

All rights reserved

Set in 10.5/14 Adobe Caslon Pro by Melissa Bugbee Buchanan Printed and bound by Thomson-Shore The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Most University of Georgia Press titles are available from popular e-book vendors.

Printed in the United States of America

19 18 17 16 15 P 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sommers, Marc, author.

The outcast majority : war, development, and youth in Africa / Marc Sommers.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8203-4884-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8203-4885-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8203-4883-4 (e-book)

1. YouthAfrica, Sub-SaharanSocial conditions21st century.

2. YouthAfrica, Sub-SaharanEconomic conditions21st century.

3. Youth and warAfrica, Sub-Saharan. 4. Africa, Sub-Saharan

Social conditions21st century. 5. Africa, Sub-Saharan

Economic conditions21st century. I. Title.

HQ 799. A 357 S 66 2015

305.24209670905dc23

2015020808

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Preface

This book is born of a growing sense that the status quo wont work. Enormous youth cohorts containing many who feel socially sidelined calls for a response that, at best, is sporadically seen. The too-common separateness of many ordinary youth raises questions about hallowed development concepts like community and civil society. Popular macroeconomic remedies for postwar African states tend to run counter to youth ambitions, toward developing rural agriculture and the formal sector while youth increasingly rush into cities and the informal economy. Domestic politics and other influences, moreover, frequently lead powerful donor agencies in faraway headquarters offices to develop priorities that are not the priorities of youth majorities. Often funds and activities are funneled into sectoral stovepipes or silos that determine in advance what will be done. People making policies that will affect youth may have little or no direct interaction with them. Elemental factors like class separation, gender difference, and police behavior may be sidestepped. Rationales for programs available to tiny minorities of youth populations may be questionable or unclear. And once initiatives get to the field, a pronounced orientation toward results usually ensues: countable indicators, outputs, and outcomes determine, to a large degree, what will constitute success. The insular process may make it difficult to figure out whether or not the initiatives left a positive, negative, or negligible impact on the people known as beneficiaries and the many more who didnt make the cut.

The presence of unprecedented numbers of young people in developing countries is not the most significant challenge to governments and international development agencies. Their alienation is. Exclusion is structured into education and cultural systems: most youth in many countries are unlikely to get to secondary school or gain acceptance as adults. Wars exacerbate their sense of separation, and not just by distancing them from traditional mores, customs, and practices. Wars also accelerate change. In many ways, youth in war and postwar Africa are learning new skills, assuming new identities, shifting to urban areas in large numbers, and shedding, when they can, traditional cultural mandates that are confining or seem pass. Conjuring male youth as dangerous and overlooking female youth doesnt square with realities in which young people, among many other things, resist engagement in violence, develop remarkable talents, and experience inclusion within excluded worlds. The world of war is terrible and transformative, inviting realizations and providing opportunities to rework what it means to be young in Africa today: how you become an adult and relate to the opposite sex, who you listen to, how you deal with your past, what you do, where you hope to go.

The Outcast Majority aims to shed penetrating light on the lives of war-affected African youth and the workings of international development. The effort begins with a discussion of the conditions, experiences, abilities, and forces that shape and propel the lives of African youth today, particularly those undergoing or emerging from war. They are contrasted with forces that influence and constrain todays international development aid enterprise. It ends by addressing the gap that lies between, proposing a framework for transforming established practice and empowering severely underestimated young people in a way that promises to make aid significantly more relevant, effective, and inclusive generally and specifically with regard to youth in war-affected Africa and elsewhere.

This books broad scope integrates two main sources of material. The first is interview data with youth in many war-affected African countries, African government and international agency officials, and development, youth, and evaluation experts. The second is archival research into the many subjects and concerns that make up the books coverage. The collective result is complementary: a series of passages featuring in-depth, firsthand analysis drawn from fieldwork in an array of countries and contexts interwoven into a narrative that covers a wide range of critical issues.

The Outcast Majority invites policy makers, practitioners, academics, students, and others to think about three commanding contemporary issues war, development, and youthin new ways. It encourages thoughtful reflection on what should be done for booming populations of youth, and not just those in nations affected by conflict in sub-Saharan Africa. In todays increasingly youth-dominated world, the issues and proposed reforms detailed here are relevant to other places where vast and vibrant youth cohorts reside.

Acknowledgments

Three events spurred the idea and development of this book. The first was in 2009, when I was invited to a dinner featuring recent graduates of a renowned graduate school for international relations. All had taken up interesting and important positions in government and nongovernment institutions, many in the international development field. I realized, over dinner and in conversation afterward, that they did not have much awareness of or interest in the impassioned debates arising from books by well-known development experts. Nor did I gauge much curiosity about what it meant to be poor. The general focus of the former students was on how you get things done.

In 2010, I applied for a fellowship from the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars to write this book. Many years of work with youth and international development agencies had illuminated a gap between what most youth need and what international development agencies normally provide. I proposed to write a book on the mismatch and how the development approach might be improved.