Poor Carolina

1981 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Ekirch, A Roger, 1950-

Poor Carolina: politics and society in colonial North Carolina, 17291776.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. North CarolinaEconomic conditions. 2. North CarolinaSocial conditions. 3. North CarolinaPolitics and governmentColonial period, ca. 16001775.

I. Title.

HC 107. N 8 E 37 330.9756'02 8039889

ISBN 08078-1475- X

For my father

ARTHUR A. EKIRCH, J R .

and my mother

DOROTHY G. EKIRCH

Contents

Figures and Tables

FIGURES

1. North Carolina, 1729

2. North Carolina, 1776

3. North Carolina: Assembly Representation, 1746

TABLES

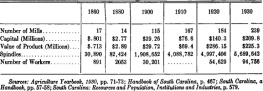

1.1 Percentage of Blacks in North Carolina's Population, 1755 and 1767

1.2 Average Annual Value of Southern Exports, 17681772

2.1 Distribution of Taxable Slaves among Pasquotank County Households, 1739

2.2 Distribution of Taxables among Perquimans County Households, 1740

3.1 Slave Ownership among Provincial Officeholders, 17311740

3.2 Land Ownership among Provincial Officeholders, 17311740

5.1 Distribution of Granville District Land Surveys, 17491754

5.2 Distribution of Granville District Patentees, Orange County, 17511762

5.3 Public Expenditures, 17541765

5.4 Slave Ownership among Assemblymen, 17641765

5.5 Land Ownership among Assemblymen, 17641765

6.1 Slave Ownership among Backcountry Justices of the Peace

6.2 Years of Experience for Backcountry Justices of the Peace, 1766

A.1 Distribution of North Carolina Landholders, 1735

A.2 Distribution of Land among Households in North Carolina, About 1780

A.3 Distribution of Taxable Slaves among Households in North Carolina, 1760s

A.4 Adult White Males Owning Twenty or More and Fifty or More Slaves in Eastern North Carolina, About 1780

Acknowledgments

It is a pleasure to acknowledge the many people who assisted in the book's preparation. I am grateful to the staffs of the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the Duke University Library, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan, the Library of Congress, the British Library, and the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland. Special thanks are expressed to Thornton Mitchell, George Stevenson, Joseph Mobley, and William S. Price of the North Carolina Division of Archives and History in Raleigh.

My largest debt is to Jack Greene. Whenever my own interest in this project waned, his was constant. Working closely with him was an invaluable experience. A. J. R. Russell-Wood, who read an early version of the manuscript, furnished intellectual adrenalin and provocative conversation. Robert Brugger, Philip D. Morgan, Sung Bok Kim, Robert Weir, and James Whittenburg generously offered their time and criticism at various stages. I also benefited from the advice of Crandall Shifflett, Rachel Klein, and Jere Daniell. Portions of were published earlier in Perspectives in American History, and they appear here with the permission of the editor, Donald Fleming. I am also grateful to him for his helpful comments.

Contemporaries from Johns Hopkins University deserve much of my gratitude. Daniel Wilson, Andr-Philippe Katz, and Paul Paskoff were all patient listeners and incisive critics of my thoughts. The book profited immensely as a result.

The Humanities Summer Stipend Program at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University supplied the resources for the study's completion. I am very grateful to Carolyn Alls, Diane Cannaday, and Lisa Donis for assistance with the typing. I also wish to thank Charles McAllister, John David Bishop, Jay Peacock, Patrick Sharpe, and Clyde H. Perdue for their help at various stages.

My family was a rich source of inspiration. My sisters and brothers-in-law were available whenever I needed fresh scenery and relaxation. My mother and father were simply tremendous. Whether it was an encouraging word or a careful reading of some early chapters, the depth of their love was always certain.

A. Roger Ekirch

Blacksburg, Virginia

August 1980

Introduction

The public life of provincial America was reasonably harmonious during the mid-eighteenth century. In contrast to earlier decades, when economic, religious, ethnic, and regional controversies had frequently plunged the British colonies into internal strife, provincial politics exhibited a notable degree of stability. That government institutions less often fell victim to the self-interested priorities of competing factions derived partly from the growing integration of early American society. Previously antagonistic interests, such as merchants and planters, Anglicans and dissenters, and rival cliques of land speculators, became increasingly interlocked by the early eighteenth century. At the same time, nearly every colony produced a governing elite, distinguished not only by its cohesion and shared interests but also by its wealth, education, ancestry, and nativity.

The authority of political leaders was consequently well established and widely acknowledged. Moreover, these elites, unlike prior generations of political leaders, did not need to view politics in essentially opportunistic terms. Just as stability was now a distinctive feature of politics for most colonies, so too was the sense of responsibility that many leaders brought to their public duties. Even in New York, famous for the factious character of its politics in the later colonial period, competing interests were reasonably restrained in their multifarious battles and were often willing to compromise in the face of civil breakdown. Political life in mid-eighteenth-century North Carolina, the subject of this work, was an exception to this dominant pattern of provincial politics. Carolina politics normally revolved around conflicting private, group, and regional interests, and resulted at times in social discord and the collapse of civil institutions.

This study is not a comprehensive political narrative but represents an attempt to analyze the most salient episodes in the colony's public life within the context of economic, demographic, social, and cultural developments. It begins in 1729, when North Carolina became a royal colony. After nearly seventy years of weak and spiritless rule, marked by provincial factionalism and periodic civil disorder, seven of the eight Lords Proprietors agreed to sell their interest in both Carolinas to the crown. Whether the resulting change in government authority affected the texture of politics, as hoped by imperial officials, is one question raised by this book. By focusing on the royal period, this study also tries to build a firmer foundation for comparing North Carolina politics with that of other royal colonies, notably neighboring Virginia and South Carolina. Further, the late 1720s marked the beginning of an important era of demographic growth and territorial expansion that, however, failed to bring substantial economic progress. The impact of these factors on the political process is a major concern of the present work. It ends on the eve of the American Revolution with the Regulator riots, an ideologically charged crusade that erupted in response to long-standing propensities within the colony's political system. Although the Revolutionary era in North Carolina still needs systematic analysis, such study is not necessary to an understanding of mid-eighteenth-century politics and lies largely outside the boundaries of this work.