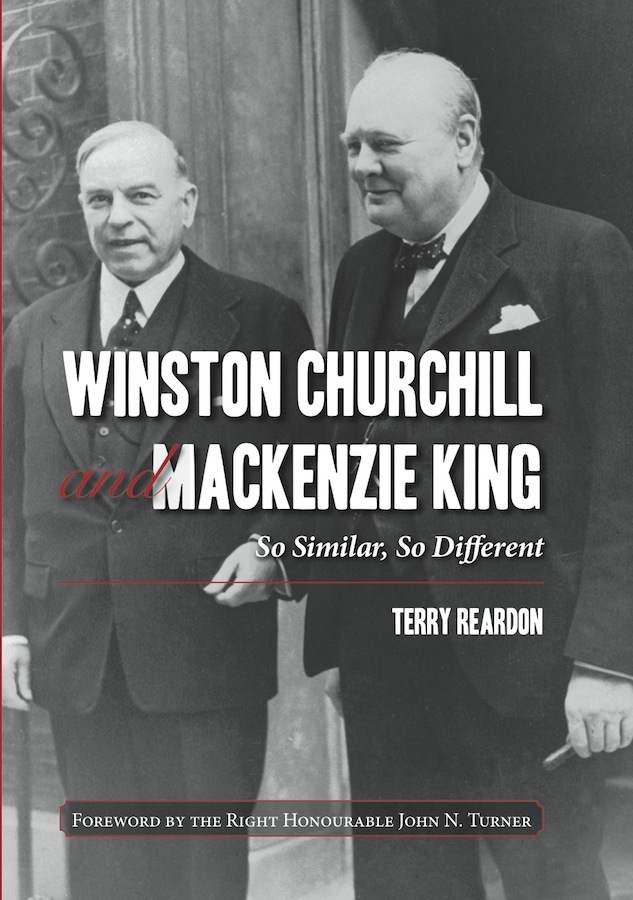

Foreword

By the Right Honourable John N. Turner,

P.C., C.C., Q.C

W hile there have been many books written on the life and times of Winston Churchill, with more appearing every year, surprising to me are the few on William Lyon Mackenzie King, who was prime minister of Canada for twenty-one years, longer than any person in that office in any country in the British Commonwealth. Thus, I am delighted that Terry Reardon has undertaken this important work on the intertwining of their political careers.

Even though it was seven decades ago, I still vividly remember meeting Churchill. It was on December 30, 1941, when the British prime minister was in the House of Commons in Ottawa, delivering one of his most famous speeches. That was the one in which he referred to the fall of France in 1940 and his attempt to have the French government go to North Africa to continue the fight. Then he said, But their generals misled them. When I warned them that Britain would fight on alone whatever they did, their generals told their prime minister and his divided cabinet, In three weeks England will have her neck wrung like a chicken. Some chicken! And when the laughter from the members had died down, Some neck! Well, the place broke up again!

The speech is best remembered for that one line, but it was also a great speech, mobilizing Canadian public opinion and bringing us up to date on the war and the nature of the unity of the Commonwealth. Now, I didnt recognize all that because at the time I was just twelve years old. I was with my mother and my sister Brenda outside the House of Commons, listening to the speech relayed by loudspeakers. Churchill was already a hero in Canada and there was a tremendous crowd. Unlike many politicians, he came out after his speech and mingled with the crowd, a gesture that was deeply moving. As Churchill came down the driveway, my mother introduced herself, then introduced Brenda and me. The great man looked me straight in the eye and said, Good of you to be here, good luck! That meeting, with the greatest person I ever met, became indelible in my memory.

That was also the occasion when the memorable Karsh photograph was taken in the Speakers chambers. Yousuf Karsh was a good friend of our family, and I used to see him over the years. He displayed a touch of genius when he yanked that signature cigar from Churchills mouth just before taking that photograph. The upset Winston Churchill scowled. The resulting photograph showed his defiance. It became the most famous one ever taken of Churchill, and has been used repeatedly ever since.

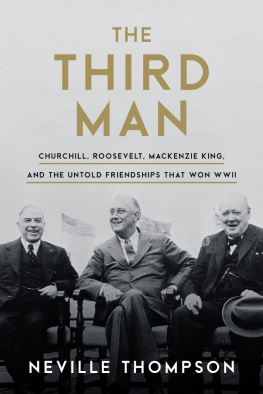

I didnt have the opportunity of meeting Churchill when I was in England as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, but my impression of him at that time, which I still hold, is that he was the greatest man of the twentieth century. It is clear in my mind that he rescued Britain and the free world. He turned the tide: one mans courage; one mans voice, coupled with his leadership, and later his close relationship with Roosevelt, were all crucial to turning near defeat into the allied victory.

Of course, the person who acted as the intermediary between Churchill and Roosevelt, before the United States entered the war, was King.

It is strange now, with all the security that surrounds major political figures, that I used to meet King when walking my dog, Blue, a springer spaniel, in Strathcona Park in Ottawa. We lived in Sandy Hill from 1934 to 1945, and Mr. Kings official residence was Laurier House, also in Sandy Hill. King was a great dog lover, and he had his terrier, Pat, with him; he took a liking to Blue, and we had a number of chats while sitting on a bench overlooking the Rideau River.

My mother was vice-chair of the Wartime Prices and Trade Board. She knew Mr. King very well, and admired his gift of compromise and also his gift of intuition. On one occasion in late 1939, she went to see the Canadian prime minister on behalf of a number of senior female civil servants, who objected to being paid so much less than their male counterparts, even though they were doing identical work. She told Mr. King that they were ready to go on strike. King responded, Phyllis, you cant go on strike; were now at war. My mother responded, Prime Minister, youll survive the war. I hope to survive the war, and then well have another chat.

Well, after the war they didnt return to that subject, but in view of her war record, King, who was quite sparse in handing out honours, recommended my mother for a CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire).

King had a remarkable career, which, unfairly, has been overshadowed by his interest in spiritualism, which was dabbled in by many prominent people during the era after the First World War. He was a superb manager of Parliament and the government, but maybe his greatest talent was his ability to select ideal people to bring into his government. Even more remarkable was the lack of any challenge to his leadership in the almost thirty years he spent as the leader of the Liberal Party of Canada. He took the country into the Second World War united, and he even managed to handle the major conscription crisis with the resignation of only one Quebec minister. He left the Liberal Party and the country in great shape when he handed over power to his successor, Louis St. Laurent.

A great friend of Churchills was Lord Beaverbrook, although in the early days this remarkable Canadian was not a political supporter. Beaverbrook was born William Maxwell Aitken in Maple, Ontario, in 1879, with his family moving the following year to Newcastle, New Brunswick. Max Aitken became a successful businessman and moved to England in 1910, where he entered Parliament and also started a newspaper chain, which included the Daily Express . He was also close to King, even though he wrote a biography of Conservative leader R.B. Bennett, who had defeated King in the 1930 election, a turn of events that in retrospect was fortunate for King as Bennett had to handle the crisis of the Great Depression.

Beaverbrook was a giant. Though not well known in most of Canada, he was much better known in Britain, where he did an outstanding job as minister of aircraft production, and later minister of supply during the Second World War. He was a good friend of my stepfather, Frank Ross, and we had him over to dinner at our house in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, on several occasions. Through that relationship, I did a little work for Beaverbrook, as a young lawyer. Beaverbrook gave the people of New Brunswick a magnificent gift: the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton the collection contains Graham Sutherlands preparatory sketches for his famous portrait of Churchill, given to Churchill by both Houses of the British Parliament on the occasion of Churchills eightieth birthday in 1954. Churchill, in thanking the members, referred to the portrait as a remarkable example of modern art; privately, he hated it, as did his wife, who later had it destroyed. The last time I saw Beaverbrook was at the Ritz Hotel in Montreal, where we downed a Scotch together.