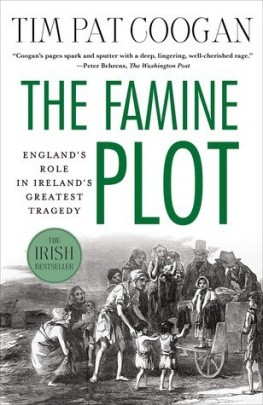

The Great Famine which ravaged Ireland between 1845 and 1850 was one of the most destructive episodes in modern history. The death toll, in terms of numbers and per capita impact, rivalled those endured in recent decades in Biafra, Ethiopia and Sudan. Over a million perished, one in eight of those alive at its commencement. Irelands population never regained its pre-Famine levels and the legacy of mass excess mortality, dislocation and forced emigration did little to reconcile the survivors to the perspective of the imperial power in London. The onset of blight was natural, but many blamed the Government for its incompetent response.

The fact that the victims perished within the comparatively developed economy of the United Kingdom was shocking and has proven controversial. Many Irish, yet very few Scots, died and this imbalance posed uncomfortable questions given that the potato-dependent poor of both countries were simultaneously affected by the scourge of blight in 1845-1846. The threatened populations of the Scottish Highlands received prompt and adequate government aid to forestall the worst effects of the food shortages. It has been argued that there was sufficient food in Ireland to feed those who died from starvation and exports of livestock and cereals to Britain certainly continued throughout the crisis. Counter-famine initiatives developed by the Government ranged in quality from inadequate to partially effective. This poor, if not disastrous, performance served to highlight the absence of the national parliament abolished by the Act of Union in 1800.

Outright starvation killed huge numbers in Ireland, as did an array of diseases that were deadly to the chronically malnourished; typhus, cholera and tuberculosis wrought havoc. Social displacement exacerbated the situation when refugees flocked to the overburdened workhouses and urban centres for relief. This often fatal secondary effect was all but inevitable given the inept manner in which the countrys primitive form of social welfare was administered. Disease travelled with the afflicted, whose numbers were such as to make quarantine and effective medical treatment almost impossible. There was no uniform policy governing the allocation of relief to the uprooted poor and various efforts to co-ordinate emergency measures resulted in lethal starvation gaps. Such failings were, at least, unintentional. The mass evictions of the later years of Famine, however, added exposure to the common causes of excess mortality. This required specific and personal human agency; bailiffs and constables were tasked to seize goods and evict tenants by landlords availing of legislation made in Westminster. None could claim innocence of the brutal consequences of dispossession.

Death was not indiscriminate: Irelands garrisons, constabulary, landlords, civil servants and clergy did not perish from want in 1845-1850. At least a million died because they could not afford to pay for meals, particularly those formerly reliant on the potato diet. It appeared as if the state either could not or would not keep them alive. Allegations of callousness stemmed from the knowledge that Irish produce flowed unabated to the towns and cities of industrial Britain. Theoretical debates on trade balance, market forces and inflation rates lacked credibility to those facing starvation, or, indeed to the Irish officials who urged the retention of shipments to meet urgent domestic requirements. Anomalies of this nature have inspired the Irish Famine Genocide Committee and others to contend that London exploited a natural crisis in pursuance of strategic political objectives. Denials based on purely economic determinants have proven decidedly unconvincing. Contemporary factors, such as British concepts of providence, moralism and laissez-faire theory, as well as base anti-Irish hostility, permit suspicion that darker forces were at work. In 1997 Britains Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair acknowledged: Those who governed in London at the time failed their people through standing by while a crop failure turned into a massive human tragedy.

Recent assessments of the Irish experience during the Famine years have produced compelling insights and increasingly view the event in its appropriate international context. While the fractured and tragic history of the Great Irish Famine awaits satisfactory analysis, this book examines the key events of the period. It explores the short- and long-term causes of the Famine, local and government responses to the crisis and the impact on Irish society.

The years 1770 to 1840 witnessed a major shift in the way in which the Irish lived. Sustained population growth was the main engine of change with significant repercussions for work practices, habitation patterns and standards of accommodation. Irelands population mushroomed from an estimated 4.75 million in 1791 to a minimum of 8.17 million recorded in the imperfect census of 1841. The limitations of this national audit meant that the real figure was probably at least 8.5 million.

Underinvestment by the Imperial government in London ensured that while the cities of Dublin, Cork and Belfast continued to grow in size from the 1820s, urbanisation lacked the capacity to absorb the human surplus on the land. The expansion of Guinness brewery in the capital and the healthy linen trade in Belfast concealed a general lack of industrial invigoration. Employment in Irelands manufacturing sector actually diminished by 15 per cent between 1821 and 1841 despite a linen-export boom centred on Antrim. This overarching negative trend contrasted with the positive experience in Britain and the Continent where mechanisation and urbanisation permanently recalibrated the relationship between town and countryside. In the twenty years preceding 1841, Kerry, Clare, Galway and Mayo registered population surges in the range of 31-38 per cent with the expansion of industry in Antrim boosting its growth rate to 33 per cent. Limerick, Tipperary, Waterford, Roscommon, Leitrim, Cavan and Tyrone increased in population by 20-26 per cent. The Irish economy initially managed to withstand the pressures accruing from accentuated social distortion in the provinces. Moreover, official statistics understated the level of population growth as they pertained to the non-emigrated population and those who could be located for enumeration. Lax port administration meant that many of those who departed went uncounted.

As before, the sustained transatlantic exodus and the employment opportunities available in Britains new cities attracted hundreds of thousands of Irish immigrants. Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool, London and other English centres gained substantial numbers of Hibernian workers and their dependents. Yet even this productive and sustained transfer did not alleviate the mounting social and economic challenges to Irish stability. Unsurprisingly, the new pressures on Irish society created new lifestyles and contingent threats. During the period in question over five times more dwellings were built on the formerly disfavoured uplands than on the more fertile, accessible and familiar lowlands. Tangible developments had occurred by 1841 when overall habitation density on the hillsides was double that of traditional low-lying farms. A virtual migration had taken place from the ancient farming belts into regions which had remained sparsely populated due to the marginal status of the soil, local climate and the lack of urgency in peopling such terrain. The rural poor of mid-nineteenth century Ireland were strongly in evidence on high-ground sites and throughout the barren west of the country where comparatively few had ventured in modern times. Transgressing the altitude barrier, an early manifestation of agrarian distress, occurred without significant hindrance by landlords.