AFTER THE

TALIBAN

OTHER BOOKS BY JAMES F. DOBBINS

Americas Role in Nation-Building: From Germany to Iraq

The Beginners Guide to Nation-Building

Europes Role in Nation-Building: From the Balkans to the Congo

The UNs Role in Nation-Building: From the Congo to Iraq

After the War: Nation-Building from F.D.R. to George W. Bush

AFTER THE

TALIBAN

Nation-Building in Afghanistan

JAMES F. DOBBINS

Copyright 2008 James F. Dobbins

Published in the United States by Potomac Books, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dobbins, James, 1942

After the Taliban: nation-building in Afghanistan / James F. Dobbins. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-59797-083-9 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. AfghanistanHistory2001- 2. United StatesForeign relationsAfghanistan. 3. AfghanistanForeign relationsUnited States. 4. Nation-buildingAfghanistan. I. Title.

DS371.4.D63 2008

958.1047dc22

2008017401

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper that meets

the American National Standards Institute Z39-48 Standard.

Potomac Books, Inc.

22841 Quicksilver Drive

Dulles, Virginia 20166

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

PREFACE

THE AFGHAN CAMPAIGN OF 2001 HAS BEEN COVERED from several perspectives. Gen. Tommy Franks, who commanded U.S. military forces, treated the period in his autobiography, American Soldier. Gary Schroen and Gary Berntsen, who led two of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) paramilitary teams that preceded the American forces into Afghanistan, told their stories in First In: An Insiders Account of How the CIA Spearheaded the War on Terror in Afghanistan and Jawbreaker: The Attack on bin Laden and al-Qaedaa Personal Account by the CIAs Key Field Commander (with Ralph Pezzullo), respectively. This work is intended to provide a similarly personal account of American diplomacy during this period.

I would like to thank my many colleagues at the RAND Corporation for all the advice, encouragement, and support they have provided. Several members of my negotiating team contributed their own recollections of our travels together in late 2001. Col. Jack Gill, my military adviser during that period, provided an invaluable chronology of our mission and recalled several evocative moments. Craig Karp provided a photographic record. Lakhdar Brahimi, the top United Nations (UN) official dealing with Afghanistan, and former Afghan foreign minister Abdullah Abdullah both helped refine my account of the events in which we all participated. Barnett Rubin, our countrys foremost expert on Afghanistan and another participant in the diplomacy of late 2001, was good enough to go over an early version of my manuscript and suggested many corrections, additions, and interpretations. Joy Merck helped correct and format more versions of this work than she or I care to recall.

From a personal standpoint, the assignment I received in October 2001 to represent the United States to the Afghan oppositionthe opportunity to head a major negotiation with broad authority and minimal guidance, backed by the full panoply of national power and buttressed by unified international supportwould have been any diplomats dream. Success attended these efforts with almost unbelievable speed. Within a few short weeks, the Taliban had been routed and a moderate, broadly based, and representative government installed in its place.

Unfortunately, this deceptively easy initial success in Afghanistan emboldened American policymakers. Before Afghanistans reconstruction had even begun, the Bush administrations attention shifted to the next campaign in its global war on terror. By early 2002, the pattern had been set for Afghanistans reconstruction. Rhetorically, President George W. Bush would hail that effort as a new Marshall Plan. Practically, it would be the most poorly resourced American venture into nation-building in more than sixty years.

Now, more than six years later, the war in Afghanistan has become more intense. Most experts believe its successful resolution is at best five to ten years off. This story is of that early triumph, those missed opportunities, and the flawed decisions that continue to shape the current Afghan conflict.

1

FIRST CONTACT

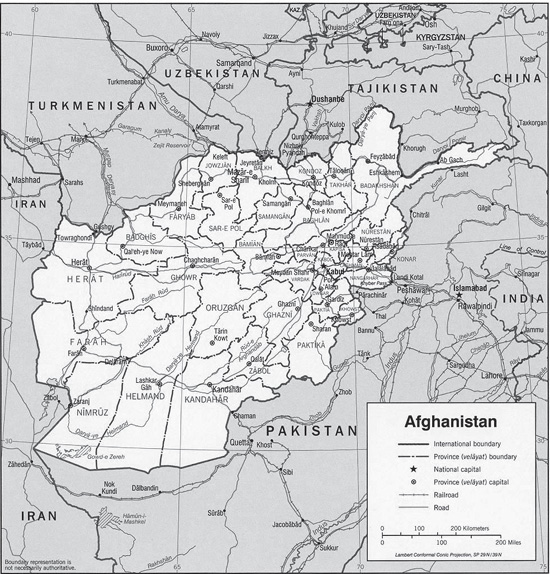

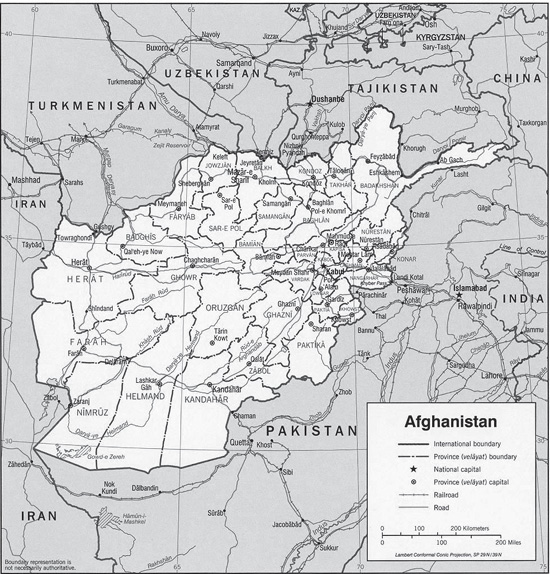

WE BOARDED OUR FLIGHT FROM TASHKENT, Uzbekistan, in the early morning. The plane was a white, unadorned Lockheed L-100, with civilian markings. It belonged to a small fleet of anonymous transports that had been flying Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agents, arms, and equipment to the Afghan resistance for the past several weeks.

We sat in bucket seats that lined each side of the fuselage. Pieces of equipment and crates of supplies were secured to the floor between us. My party included representatives of the secretary of defense, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), and the CIA director. We composed the first American diplomatic mission to enter Afghanistan in more than twelve years.

Accompanying us was a small group of Afghans, led by a medical doctor whom I had met for the first time the previous day. Dr. Abdullah Abdullah was a comparatively young man, perhaps forty years old. He was a protg of Ahmed Shah Massoud, the charismatic military leader of the Afghan resistance, and he had served as its primary liaison with the outside world. Al Qaeda agents had assassinated Massoud several weeks earlier, just two days before their attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

As we waited on the tarmac for takeoff, an Uzbek customs official sporting enormous, saucer-shaped, Soviet-era military headgear came on board to stamp our passports. Clandestine or not, our group had to observe local border formalities.

Once our aircraft had reached cruising altitude the pilot invited Abdullah and me to join him on the flight deck, where we had a stunning view of the mountain ranges below and could enjoy greater privacy than the main cabin afforded. Here we were also better insulated against the engine noise. For the next two hours we held our first private conversation.

Dr. Abdullah was in a delicate position. He represented a regime that, until a few days earlier, had been little more than a government in exile. Since its ouster from the capital of Kabul in 1996, the Northern Alliance had controlled a steadily diminishing sliver of Afghan territory. For the past couple of years its troops had operated out of mountainous strongholds along the borders with Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, using arms and money the governments of Russia, Iran, and India supplied, and had challenged the Taliban regime in Kabul. Along with the Talibans own record of abuse and misgovernment, the Northern Alliances efforts had been sufficient to deny that regime international legitimacy, but the Northern Alliance had posed no real threat to the Talibans hold on the country.

The power balance in Afghanistan began to change rather dramatically in the weeks following al Qaedas attacks on New York and Washington on September 11, 2001. By early November, Northern Alliance forces, their combat effectiveness greatly enhanced by American airpower, had routed Taliban formations guarding the provincial capital of Mazar-e-Sharif. Three days later the Northern Alliance had breached the capitals last defenses and marched into Kabul.

Next page