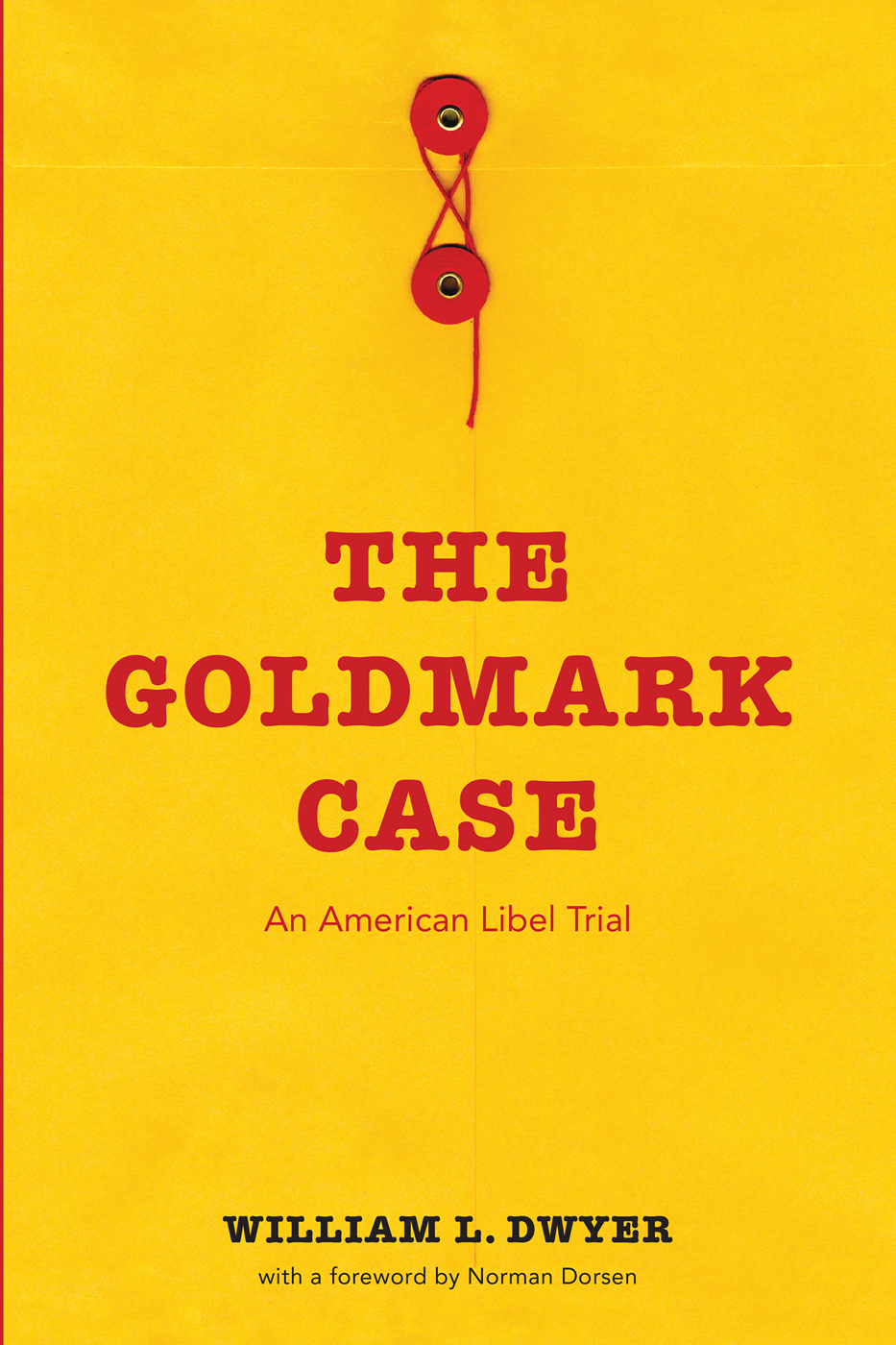

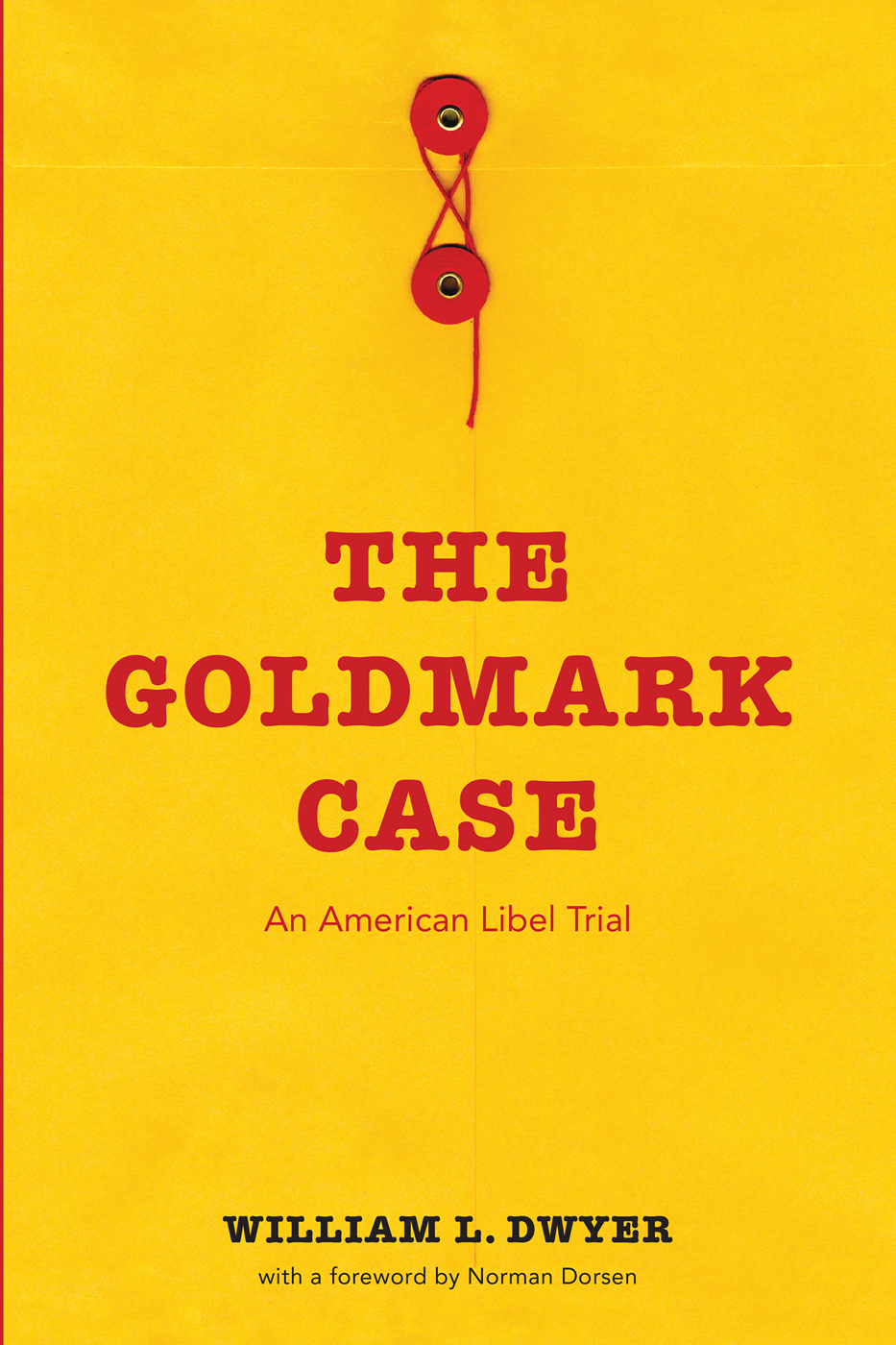

The Goldmark Case

An American Libel Trial

The

GOLDMARK

CASE

An American Libel Trial

WILLIAM L. DWYER

With a Foreword by Norman Dorsen

University of Washington PressSeattle & London

Copyright 1984 by the University of Washington Press

First paperback edition 2015

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Audrey Meyer

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Dwyer, William L.

The Goldmark case.

1. Goldmark, JohnTrials, litigation, etc. 2. Canwell, AlbertTrials, litigation, etc. 3. Trials (Libel)Washington (State)Okanogan. I. Title.

KF228.G65D851984 | 345.73'0231 | 84-40326 |

ISBN 978-0-295-99486-4 | 347.305231 |

Contents

To Vasiliki, Joanne, Tony, and Charlie

FOREWORD

G EORGE SANTAYANAS dictum that those who ignore history are condemned to relive it has achieved the notoriety of a clich. Like many clichs it survives because it contains much truth.

The Goldmark case brings these thoughts to mind as it beckons us to reflect on the phenomenon known as McCarthyism. The word is (or should be) permanently listed in the Devils Dictionary. It signifies a particularly irresponsible form of persecution for political beliefs. It also conveys a total lack of due process and fairness whereby unverified allegations, made by rabid and often mercenary ideologues, are used to destroy reputations, careers, and families. Too often these tactics are used against strangers within the gatesrecent arrivals to a community who are not of the dominant race, religion, or cultural background.

Most Americans eventually were repelled by what Senator Joseph McCarthy and his allies wrought in the early 1950s and, after viewing the televised Army-McCarthy hearings, gladly assigned him to a purgatory from which he never emerged. But since memories are short, William Dwyer has rendered a high public service in setting down for this generation a harrowing western courtroom drama that will, if it is as widely read as it deserves to be, fortify Americans to resist new attempts to violate civil liberties and debase the political community.

The setting for the Goldmark case was a sparsely populated area in north central Washington, where John and Sally Goldmark moved soon after his completion of naval sevice in World War II. Goldmark was a city-bred easterner and an honors graduate of Harvard Law School, but he chose to become a rancher in remote territory. The ranch prospered with hard work, and the Goldmarks became active in community and charitable affairs. John was elected to the state legislature in 1956 and reelected twice. After six years in office he was the respected chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee.

And then the trouble started. Goldmark was a liberal legislator during a time of suspicion toward liberals. Worse, as a young woman Sally had been a member of the Communist Party for a few years. Although there was no indication of any illegal activity, and she left the Party soon after her marriage, the record of her membership was there to be used. And it was.

Early in 1962, as the legislative election campaign started, a county weekly reported that Goldmark was running on a platform which advocates the repeal of the McCarran Act, a law requiring the registration of all Communist Party members; that his son Charles was a sophomore at Reed College, the only school in the Northwest where Gus Hall, secretary of the Communist Party, was invited to speak; and that he was a member of the American Civil Liberties Union, an organization closely affiliated with the Communist movement in the United States. A whispering campaign about Sally Goldmark began at the same time. The libels proliferated through the campaign.

John Goldmark lost the election badly, and he also lost his good name. Rejecting the advice of those who warned that a public trial would cause further harm to him and his family, he promptly brought a libel suit to vindicate his reputation against individuals and periodicals who, he charged, had conspired to ruin him. He hired William Dwyer as his chief counsel.

The trial began on November 4, 1963, and attracted national attention. Witnesses crossed the country to testify on Johns character, the threat of Communism to American society, and assorted related issues. In the third week of the trial Lee Harvey Oswald murdered President John Kennedy, and although a recess was taken, Goldmarks friends feared that this shattering event would implicitly support the defendants claim that an indigenous Communist conspiracy was afoot to destroy American institutions.

The case was tried to a jury of rural westerners. No summary can do justice to the tense and colorful drama that filled the courtroom. No morality play could more sharply etch the roles of parties and witnesses. No novel could more vividly capture the political emotion. What a challenge to the jury of ordinary men and women of Okanogan County! And what a performance by the jury in piercing the super-patriotism of Goldmarks accusers and, with consummate common sense, rendering justice to a man foully charged with disloyalty. One wonders if a single judge, no matter how learned or brilliant, could have matched the jurys distilled personality of the community in rehabilitating Goldmarks name.

As noted earlier, a particularly scurrilous set of charges concerned the American Civil Liberties Union. Herbert Philbrick, a counterspy for the FBI and witness against Goldmark, called the ACLU not just red, but a dirty red. A local newspaper attacked the ACLU as an instrument of the Communist apparatus. One of the defendants in the trial said that ninety percent of the ACLUs work was defending Communists. Another defendant said that the ACLU was classified as a Communist front in 1948 by a California legislative committee, although he neglected to mention that the same committee subsequently cleared the ACLU.

The jurys verdict completely vindicated both Goldmark and the ACLU. When he reviewed the verdict and the evidence, the judge found explicitly that the ACLU was not a Communist front organization. As president of the ACLU, I know that the communist front charge is and always has been totally false; yet it was repeated many times, before and even after it was refuted in a court of law at Okanogan.

The drama did not end with the jurys verdict. In March 1964, the United States Supreme Court altered the constitutional rules relating to libel. It held in New York Times v. Sullivan that false statements about public officials are protected free speech under the First Amendment unless uttered with actual malice, that is, with knowledge that they are false or with reckless disregard of the facts. How this Supreme Court ruling for free speech eventually had its impact on the Okanogan verdict provides an ironic but satisfying ending to the story of the Goldmark case.

John Goldmark may have been more valuable to the country he loved because of the calumnies hurled against him and his successful struggle for vindication than if he had lived a conventionally successful life. But what a price this victory exacted, personally and politically. John and his family had to face the shocked reaction of their neighbors when the case broke, and then endure a trial of excruciating tension in which their entire lives were publicized, raked over, and submitted to the judgment of strangers. It is difficult for someone who has not lived through such an ordeal to appreciate what it must mean in human terms.

Next page