Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

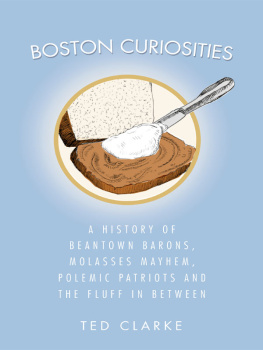

Copyright 2010 by Ted Clarke

All rights reserved

All images within this book are from Wikipedia.org, the authors collection and Damrellsfire.com.

Front cover image: Cornhill, Boston, 1962.

First published 2010

e-book edition 2012

ISBN 978.1.61423.370.1

Clarke, Theodore G.

Brookline, Alston-Brighton, and the renewal of Boston / Ted Clarke.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-185-7

1. Urban renewal--Massachusetts--Boston--History. 2. Social change--Massachusetts--Boston--History. 3. Community life--Massachusetts--Boston--History. 4. Brookline (Mass.)--Social conditions. 5. Brighton (Boston, Mass.)--Social conditions. 6. Brookline (Mass.)--History. 7. Brighton (Boston, Mass.)--History. 8. Boston (Mass.)--Social conditions. 9. Boston (Mass.)--Politics and government. 10. Boston (Mass.)--History. I. Title.

HT177.B6C55 2010

307.34160974461--dc22

2010045558

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Introduction

In the first half of the nineteenth century, Boston, with new confidence, built itself into the fourth-largest industrial city in the country. It reached that level by 1880. But it would hit its zenith shortly after that and go into a dreary decline.

Switching from a maritime to a manufacturing economy, filling in the Back Bay when land became scarce, solving traffic snarls by digging North Americas first subway and establishing a cultural haventhese are all things that suggest forward thinking and a good deal of flexibility.

Brighton and Brookline, close to Boston and to each other, began to grow, especially as Boston became overly crowded. They grew mostly along the lines of public transportation that were built within them, but they grew at different rates and in different ways. In due time, they went their separate ways.

The town of Brighton became part of the city, while Brookline voted to remain separate for its own reasons. Each had its own distinct spurs to growth, and they continued to grow, both doing better than the downtown in the decades up through the Second World War. In the period following that, Brighton fell victim to the same loss of middle-class people to the suburbs as Boston did. Brookline, a suburb itself, had sustained growth through this same period.

By the early decades of the twentieth century, Boston was no longer a world-class city; it was a city in declinea city in the doldrums. It showed no creative spark, no progress and little hope.

What happened? How does a place become mired in depression? What made all that bright hope vanish? And then, what happened to allow Boston to make a comeback? Who would lead its resurgence and how did they do it? This slim volume will tell you those things and more.

Chapter 1

Recovering from the Great Boston Fire

By the time of the Great Boston Fire, November 9, 1872, Boston was beginning what others and I have called its first golden age. At that time, the Back Bay was unfinished, and most of the cultural institutions had yet to move there from downtown. But the fire would change all that.

The fire began on the corner of Summer and Kingston Streets, a block south of where Macys stands today, and it spread rapidly. It took a long time for someone to use the call box and report it. In fact, the fire was seen from hilly Charlestown before it was reported. Ironically, fire alarm boxes were kept locked at that time in order to prevent false alarms. It took twenty minutes to get the key and call in the alarm from a nearby box.

Viewers from Charlestown had balcony seats as the bright, moonlit night made everything clearly visible, and the hot fire with its plumes of flame provided not only lighting to the scene but drama as well.

Locked call boxes werent the only complication. Another difficulty is highlighted in many tellings of the story. An epidemic of horse flu had sidelined the animals that pulled the fire equipment, so it instead had to be hauled by volunteers on foot. Nonetheless, these men had been trained. They pulled with a will and were only somewhat slower than the horse-drawn teams would have been. Horse flu was but a sidebar to the main story.

Equipment moving at any speed might have been too slow since the fire spread quickly, particularly through the top floors of buildingsconnected or near one anotherwhere combustible materials were stored and where the wooden French mansard roofs often caught fire from flying embers. This problem was made more serious by the inability of the steam engine pumpers to draw sufficient water to reach the tops of tall buildings in the narrow streets, particularly Summer. That was because the six-inch pipes in this section of town were too narrow to provide enough pressure to project the water five stories high.

Gas lines were used for lighting within the buildings, and many of these burst into flame before they could be shut off. Postmaster William L. Burt, who would play a major role in fighting the fire, described what he witnessed: I saw in the most intense part of the fire, huge bodies of gas; you might say 25 feet in diameterdark opaque masses, combined with the gases from the pile of burning merchandiserise 200 feet in the air and explode, shooting out large lines of flame fifty to sixty feet in every direction, with an explosion that was marked as the explosion of a bomb.

The fire was stopped at State Street by a brigade of firefighters with pumps, saving the Old State House for posterity. Also saved by extraordinary effort was the Old South Meetinghouse at Milk and Washington. Credit is given to a crew from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, who arrived by train with their steam engine, Kearsage No. 3, that had been loaded on a flatbed railroad car and hauled by train to Boston. Its crew hitched it to a hydrant and soaked the roof of the church with a steady stream, thereby saving it.

What became known as the Great Boston Fire took about twelve hours to contain. By that time it had destroyed about sixty-five acres in the business section of the city in an area between Summer, Washington and Milk Streets and the ocean. That included 776 buildings at a cost of nearly $75 million and thirteen deaths.

Great Boston Fire, 1872.

Ruins of the burned district.

The spread of flames may have been curtailed by blowing up buildings with gunpowder, leaving gaps that in some cases the fire could not bridge. A controversial tactic at best, this was done at the fervent insistence of the postmaster, William L. Burt, who had help from General Henry Benham, who brought gunpowder from Castle Island, which was where he was posted. The chief fire inspector had reluctantly agreed to try it, and it was not done by approved methods. In the

Next page