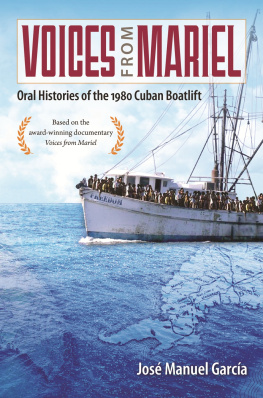

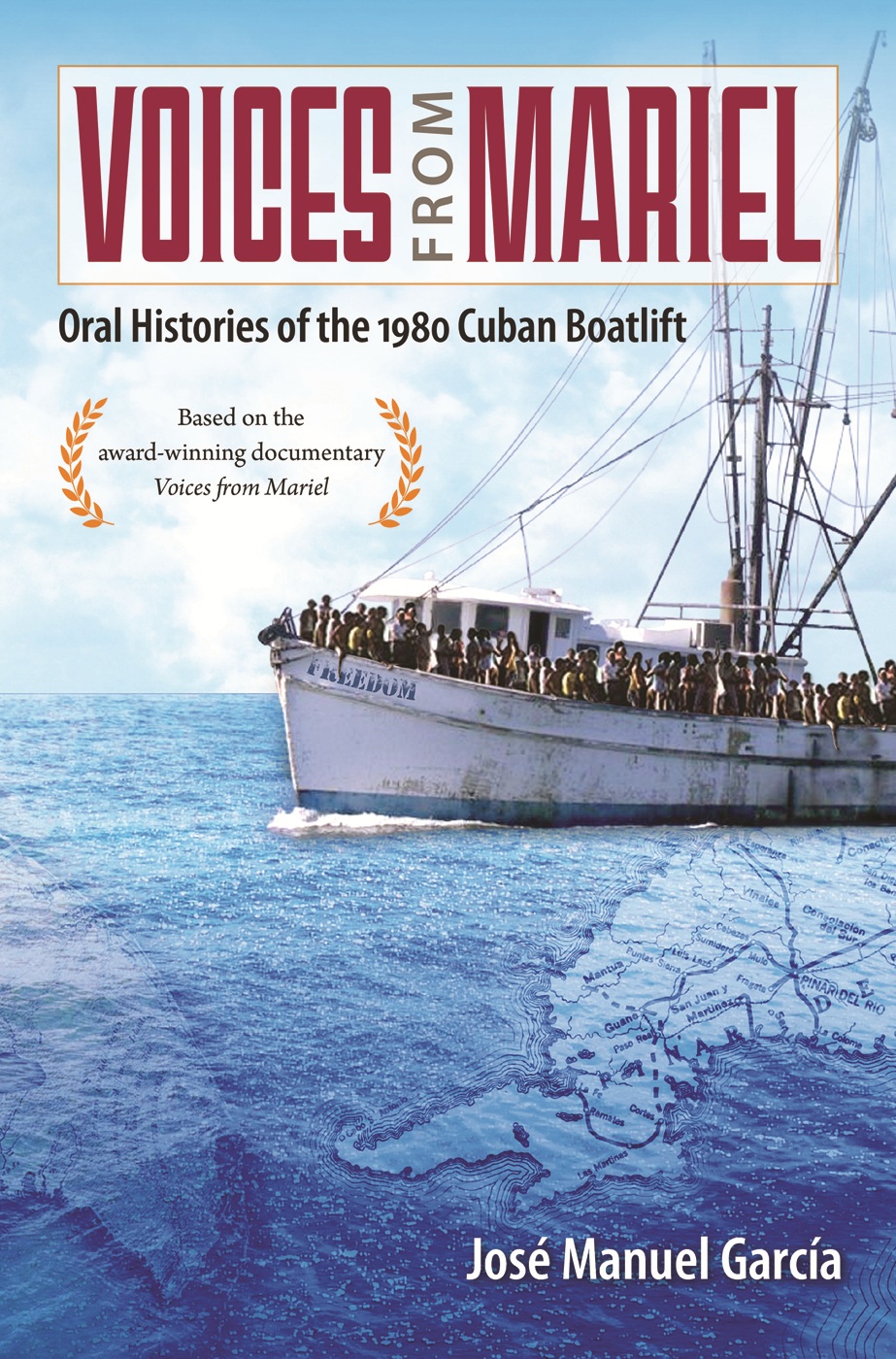

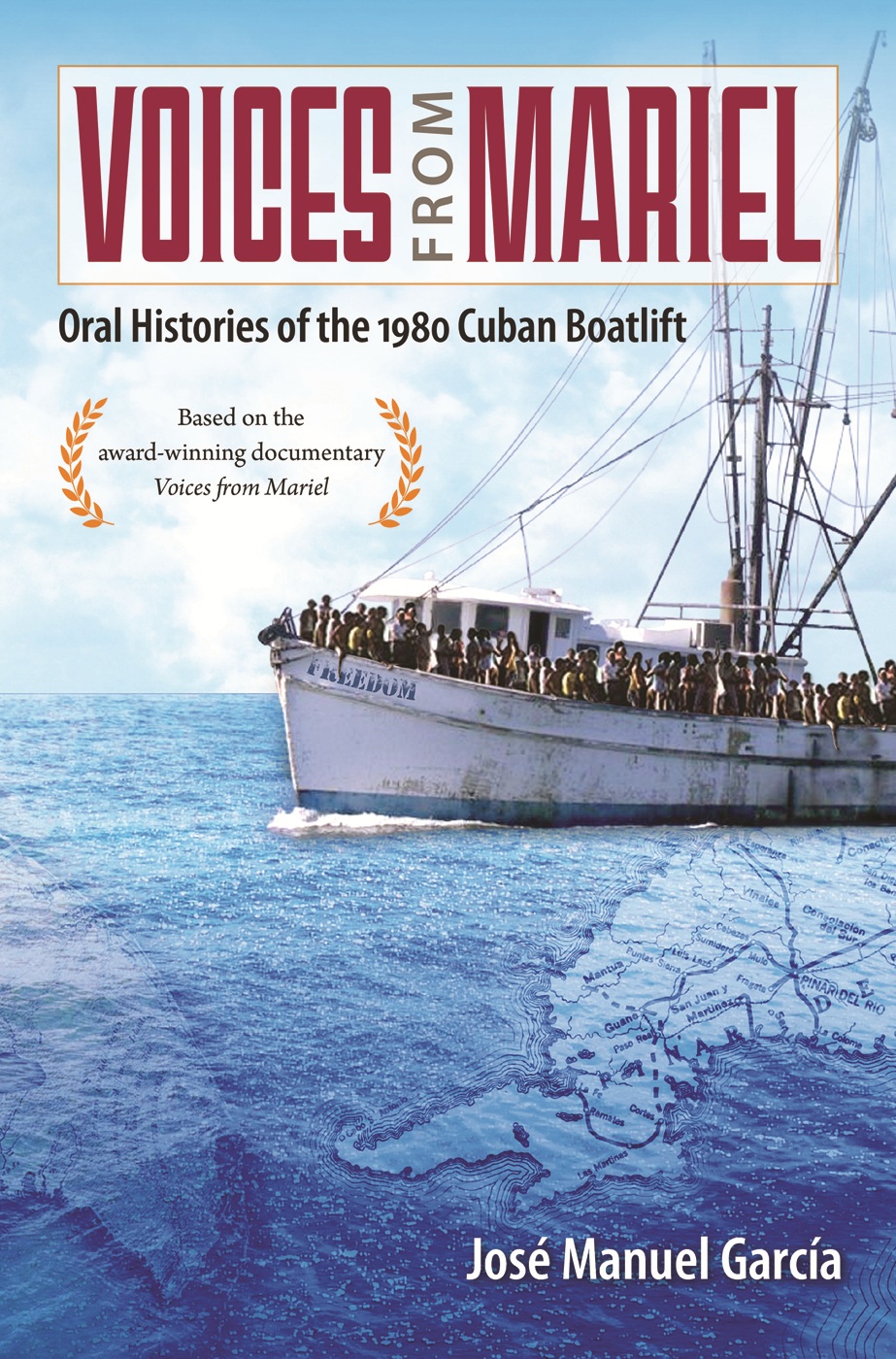

VOICES FROM MARIEL

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF FLORIDA

Florida A&M University, Tallahassee

Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton

Florida Gulf Coast University, Ft. Myers

Florida International University, Miami

Florida State University, Tallahassee

New College of Florida, Sarasota

University of Central Florida, Orlando

University of Florida, Gainesville

University of North Florida, Jacksonville

University of South Florida, Tampa

University of West Florida, Pensacola

VOICES FROM MARIEL

Oral Histories of the 1980 Cuban Boatlift

JOS MANUEL GARCA

University Press of Florida

Gainesville Tallahassee Tampa Boca Raton

Pensacola Orlando Miami Jacksonville Ft. Myers Sarasota

Copyright 2018 by Jos Manuel Garca

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

This book may be available in an electronic edition.

23 22 21 20 19 186 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017947610

ISBN 978-0-8130-5666-1

The University Press of Florida is the scholarly publishing agency for the State University System of Florida, comprising Florida A&M University, Florida Atlantic University, Florida Gulf Coast University, Florida International University, Florida State University, New College of Florida, University of Central Florida, University of Florida, University of North Florida, University of South Florida, and University of West Florida.

| University Press of Florida 15 Northwest 15th Street Gainesville, FL 32611-2079 http://upress.ufl.edu |

To all the Marielitos and their children because this is also their story.

To my family: Pepe, Esther, Letty, Anabel, and Alex Garca.

To my dear wife, Debbie Graham, for her constant support and encouragement over the years.

Contents

Interviews

Preface

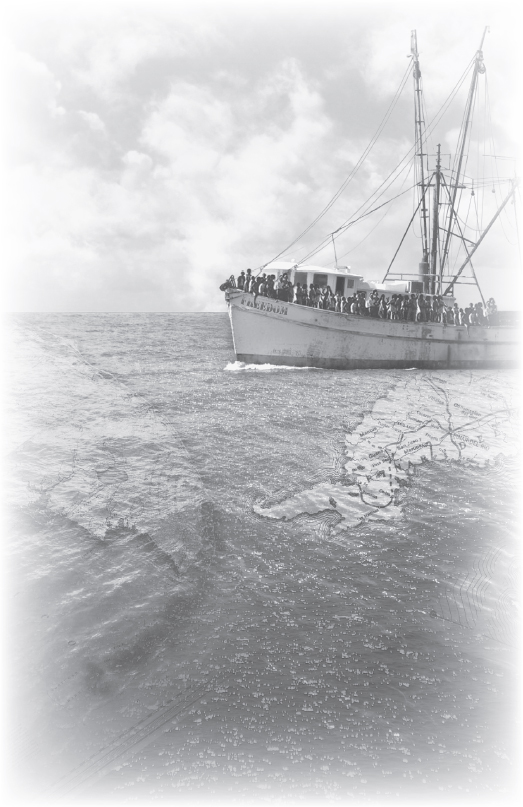

The Mariel boatlift can be described as one of the largest exoduses of modern history and is undoubtedly Latin Americas largest sea-borne migration in such a short period of time. More than 125,000 Cubans left their homeland through the Mariel Port in less than six months looking for freedom and a better life. The boatlift not only changed the lives of those who left; it also transformed both the United States and Cuba in ways that we may never fully understand.

This sudden mass migration of thousands of Cubans sent a loud and clear message to the Cuban government and the international community that socialism, or at least Cubas version, was not living up to its promises. It called into question, perhaps for the first time, the so-called triumphs of Latin Americas most successful revolution. This was a government that for twenty years had appeared to have the full support of its people and the international community, where all citizens were guaranteed universal health care and a free education. The boatlift challenged that image forever.

Unlike in the 1960s, when most Cubans who had left the island belonged to the so-called capitalist classes, now it was the youth who wanted out. Young men and women who had been born or grown up with the revolution wanted to break free from the system. That freedom presented itself when Hector Sanyustiz drove a bus through the Peruvian embassy wall.

Shortly after the invasion of the embassy, the Cuban government media began a smear campaign that characterized the refugees as traitors, criminals, and social parasites who did not belong in any society. They were the so-called escoria, the filth of society. This was a stigma that persistently followed the immigrants for some time as they tried to settle in their new homeland and that still continues in the minds of many people who remember the 1980 Cuban exodus.

This book provides an oral history of the Mariel boatlift. It attempts to capture and record for posterity the human experience, drama, and complexity of this mass migration through the voices of its primary witnessesincluding me. I was thirteen when a bus crashed through the gates of the Peruvian embassy in Havana, setting into motion a series of events that would forever change my life and the lives of many others. It resulted in my departure from my homeland, where I had spent my childhood, and to which for many years to come I would long to return.

What originally began as an oral history to be published in a book eventually turned into a very personal and emotionally painful journey that brought me face to face with many ghosts of my past. It also sparked a desire to return to my homeland to capture on video the other side of the Mariel story. As I began interviewing for the documentary, I discovered that friends, family, and my students were captivated by the stories. Their powerful reaction was the best signal that my story and those of other Marielitos needed to be told to a wider audience. Jesse Larson, one of my Florida Southern College students, approached me about making a documentary and put me in contact with NFocus, a local filmproduction company. This talented group of filmmakers quickly became Marielitos themselves as we all embarked on a journey to recapture an important part of Cuban American history on camera.

It was with their encouragement and professional support that I finally decided to return to my homeland to explore the other side of the Mariel exodus and the story of those I had left behind. While back in Cuba, I was deeply moved by the resilience of the Cuban people, their warmth, and hospitality. I also felt a powerful connection with the island, despite my many years of absence. I am very grateful to the United States for allowing me to experience freedom and contribute to this great nation. As you read on you will see how many Marielitos are grateful to the United States for providing them safe harbor. I also dream of the day when I can somehow make a contribution to my homeland again.

From the beginning of this project, I was aware that I could not just tell the story of the Mariel boatlift of 1980, but that I needed to shed some light on the Marielitos themselves. I wanted to show how the Marielitos are a diverse group of people from various social, religious, and professional backgrounds. Some were farmers, doctors, students, and political prisoners; others were people who could not freely practice their religious faith; while others had been persecuted for their sexual orientation. There were seventy-year-old women and six-year-old children. But most were young adults in their early to mid-twenties who had grown up with the Cuban revolution. I was fortunate to capture many of these important stories and share them with the world.

The Mariel subjects in this book represent the diversity of Cuban society in 1980. Most are also representative of any average American citizen today. Some have attained a higher degree of economic and professional success than others. However, what is most consistent is that the majority of Marielitos seem to be hardworking citizens who in many ways have been successful in erasing some of the stigma that once accompanied them.

Most of the interviews in this book took place in 2010 and 2011 in Florida and were conducted in both English and Spanish. Despite the difficulties that occur with any translation, I have made every effort to capture the essence of the stories that appear in both the book and the documentary. With this in mind, I have also made some minor editorial changes in order to enhance the readers understanding of the political, geographical, and social context of the time.

Next page