Table of Contents

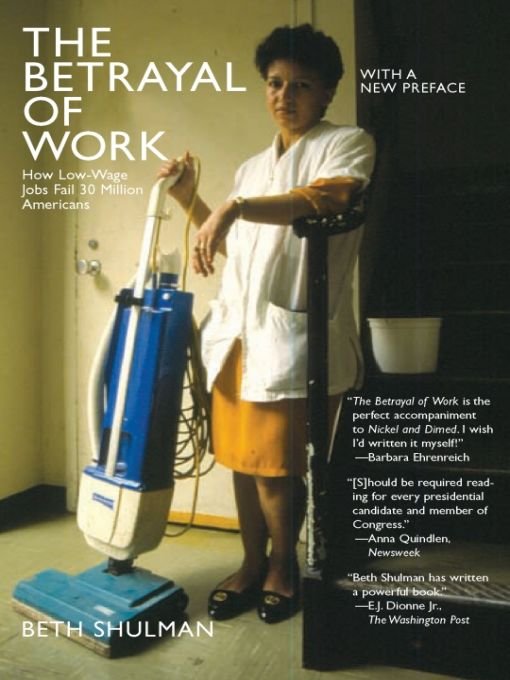

Praise for The Betrayal of Work

Shulman... hits a theme of timeless importance: the mistreatment of low-wage workers in America and what can and should be done about it. This slim, graceful book speaks to the condition of 30 million working Americansthose at the bottom of the working barrel. It combines personal vignettes, social statistics and policy prescription in a wonderfully readable manner.... Shulmans book is a model combination of compelling portraiture, common sense and understated conviction. She would evidently make a splendid secretary of labor in the next civilized administration. In the meantime, everyone should read her book.

James K. Galbraith, The American Prospect

We praise hard work all the time. But as a society, we do very little for those who work hard every day and receive little reward for what they do. Beth Shulman has written a powerful book on the subject. Attention should be paid to her indictment.

E.J. Dionne Jr., The Washington Post

Betrayal shows how working lives can get nasty fast.... [Shulman] presents compelling, detailed evidence of the futility of millions of American workers.

Linda M. Castelitto, USA Today

Shulman documents the personal storiesand explodes many of the mythsof Americas lowest-paid workers.

Nicholas Stein, Fortune

Shulman... has gathered an impressive array of studies and statistics on the army of working poor.

Aaron Bernstein, Business Week

[This book details] with fresh data how pervasive low-wage incomes are in a country that continues to undercut what it should value most... [This is a] vital book [that] should have been memorized as preparation for the [2004 presidential] campaign.

Thomas Oliphant, The Boston Globe

In this book, we meet call center workers, child care workers, janitors, poultry-processing workers, home health care aides, guest room attendants, pharmacy assistants, and receptionists. Anyone reading this book will be hard-pressed to walk down the supermarket aisle, visit a nursing home, hotel, or office with the same myopic vision they had before reading it.

Gwendolyn L. Evans and Paula B. Voos, Labor Studies Journal

Reminiscent of Barbara Ehrenreichs best-selling Nickel and Dimed, Beth Shulmans The Betrayal of Work offers a compelling and disturbing portrait of poverty in the American workplace... But readers will not be left without hope for this marginalized segment of the workforce. The Betrayal of Work concludes with a chapter that specifically outlines how structural changes in the economy may be achieved, thus expanding opportunities for all Americans.

Working Knowledge for Business Leaders, Harvard University

An exhaustively researched, quietly passionate book.

Joan Oleck, Ford Foundation Report

Shulman passionately argues, in the spirit of Robert Putnams Bowling Alone, that underpaid, unstable workers without health care are problematic not only for those unfortunate workers and their families, but for society as a whole.... Shulman provides both a cautionary tale, but also viable and concrete policy solutions, as well as success stories that have enabled win-win situations.

Don Klotz, Center for Urban Regional Policy at Northeastern University newsletter

Shulman combines personal stories with extensive research on working conditions, pay, and benefits for low-wage workers, and the effects on the ability of these families to afford a safe and decent standard of living. She paints a grim picture of life on the margins and yet constantly reminds the reader that there are too many of these workers to consider them marginal.

Heather Boushey, Challenge Magazine

Shulman uses both case studies and statistical evidence to support her contention that, while Americans have historically believed that hard work ensured security, that promise has been broken and as a nation we are living a lie.

Ellen D. Gilbert, Library Journal

To my husband, Ernie

for his love and support

and

To Aaron

who makes every day a blessing

Is this improvement in the circumstances of the lower ranks of the people to be regarded as an advantage or as an inconveniency to the society?... It is but equity... that they who feed, cloath and lodge the whole body of the people, should have such a share of the produce of their own labour as to be themselves tolerably well fed, cloathed and lodged.

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations

You shall not abuse a needy and destitute laborer, whether a fellow countryman or a stranger in one of the communities of your land.

Deuteronomy 24:14

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people helped make this book possible. I am especially indebted to Lance Lindblom and Eric Wanner. From the very beginning, they gave me their encouragement, support, thoughtful suggestions, and their precious time. Words cannot convey my gratitude for their enormous generosity. I am also thankful to the Ford Foundation and the Russell Sage Foundation for their initial funding that allowed me to take a leave of absence and focus on this book.

From the outset, I was aided with a gifted editor, Steve Fraser. He shared my passion for this issue and helped steer me through the process with his exceptional knowledge and keen editorial skills. He kept me going in difficult times, but never failed to give me needed criticisms. I want to thank The New Press who provided me with a talented editor, Andy Hsiao, who continually pushed me to make this a better book and whose comments were enormously helpful.

My friend and colleague Jack Meyer read the manuscript in each of its permutations and provided me with invaluable insights and assistance with technical data. His critiques provided a more balanced viewpoint. He and his colleagues at the Economic and Social Research Institute were generous with their time, for which I am very thankful.

I also want to thank Andy Stern and John Wilhelm for sharing their perspectives on the labor movement and helping me with connections with workers; Richard Freeman, Larry Mishel, Jared Bernstein, and Paul Osterman, whose excellent work in this area and comments brought a clearer view of the problem; Joan Williams and Heidi Hartmann for their help on issues involving work and family; Annette Bernhardt for helping me understand the depths of the low-wage mobility problem and introducing me to some creative projects that help; Laurie Bassi for her help on training issues; Katherin Ross Phillips for her assistance in providing data on low-wage workers; Kathy Bonk and Janet Shenk, who read the final draft of the manuscript and provided helpful suggestions; members of the Domestic Strategy Group of the Aspen Institute, whose knowledge and give-and-take helped me think about these issues more creatively; Damon Silvers, who helped bring me to this point; Politics and Prose, for providing such a wonderful place to write; and to the many other people, many of whom are cited in the endnotes, who gave me their valuable time and assistance. Of course, it goes without saying, any mistakes in this book are all my own.

My deepest debt of gratitude goes to the workers who were willing to tell me their stories. They welcomed me into their homes, fed me, and shared their lives. It was an honor that I will always cherish. And to my family and friends who have heard more about this book than they wished, yet supported me at every turn.