Shannon Bontragers Death at the Edges of Empire joins a list of other seminal works on war and memory, such as Kristin Hasss Carried to the Wall. He shows the importance of culture on shaping American narratives regarding war. It is a very important addition to the literature. Highly recommended!

Kyle Longley, author of Grunts: The American Combat Soldier in Vietnam

Dense and absorbing. Im particularly impressed by Bontragers deft rhetorical analysis of various speechesmany of them by presidentsdelivered at remembrance functions between 1863 and 1921.... This is is an effective way of tracking the ideological twists and turns in American war commemoration. In addition, the author knows how to tell a story. Some of my favorite sections of this book are simply compelling narratives.

Steven Trout, author of On the Battlefield of Memory: The First World War and American Remembrance, 19191941

Studies in War, Society, and the Military

General Editors

Kara Dixon Vuic

Texas Christian University

Richard S. Fogarty

University at Albany, State University of New York

Editorial Board

Peter Maslowski

University of NebraskaLincoln

David Graff

Kansas State University

Reina Pennington

Norwich University

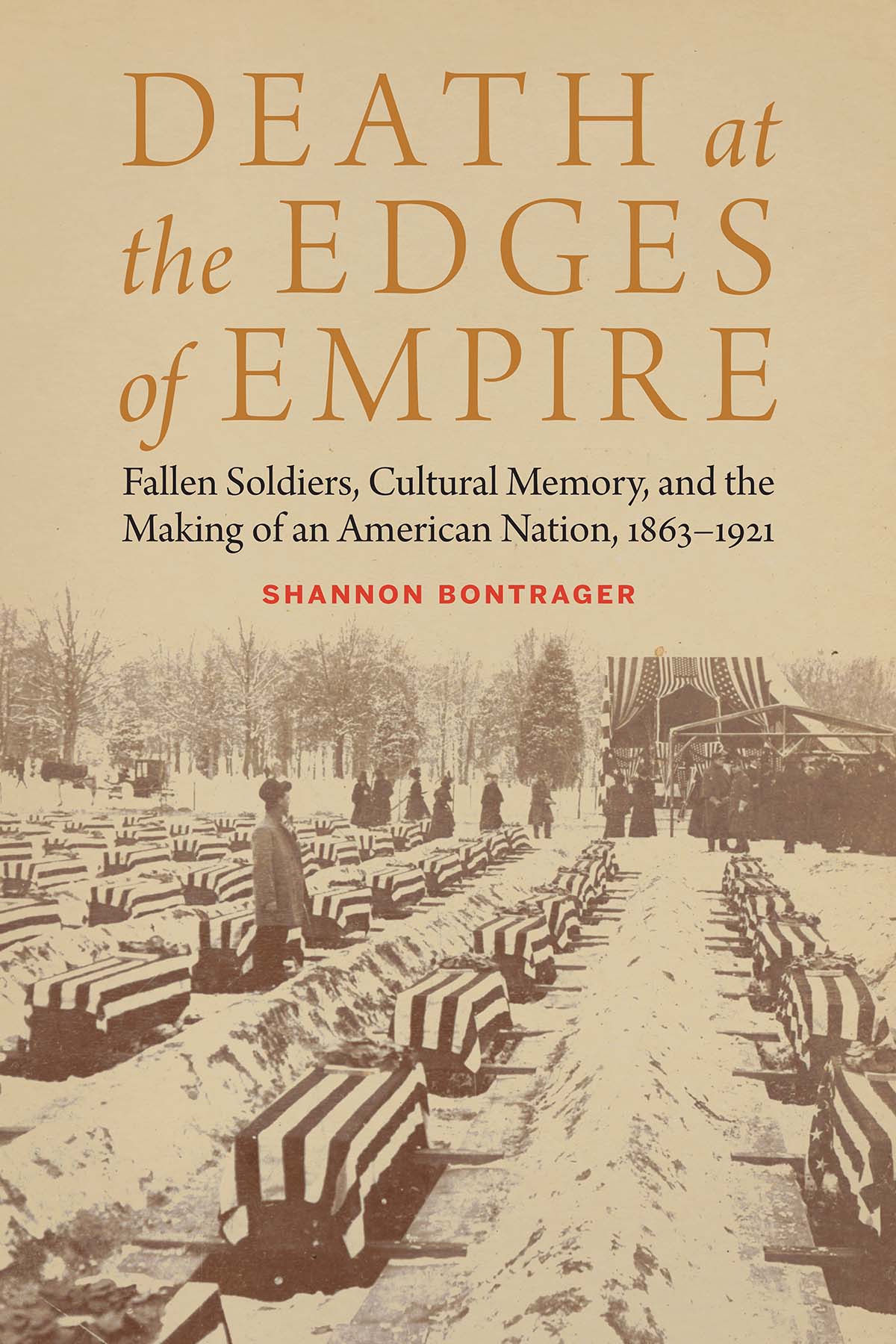

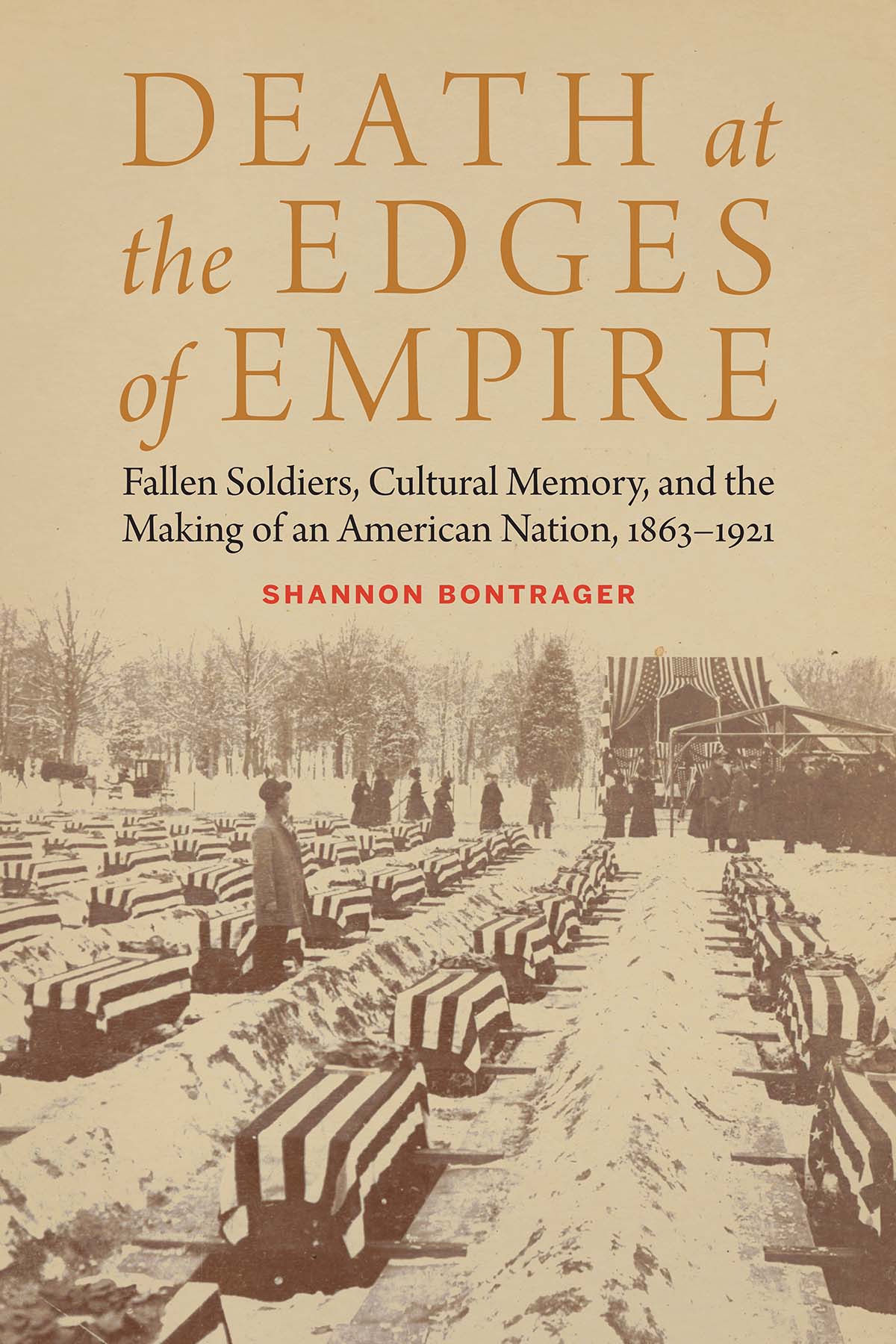

Death at the Edges of Empire

Fallen Soldiers, Cultural Memory, and the Making of an American Nation, 18631921

Shannon Bontrager

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln

2020 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image courtesy of the Digital Common-wealth.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bontrager, Shannon, author.

Title: Death at the edges of empire: fallen soldiers, cultural memory, and the making of an American nation, 18631921 / Shannon Bontrager.

Description: [Lincoln, Nebraska] [University of Nebraska Press], [2020] | Series: Studies in war, society, and the military | Extensive and substantial revision of the authors thesis (doctoral)Georgia State University, 2011, titled Nationalizing the dead: the contested making of an American commemorative tradition from the Civil War to the Great War. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: Shannon Bontrager examines the culture of death, burial, and commemoration of fallen American soldiers in the Civil War, the Spanish-Cuban-American War, the Philippine-American War, and World War I. He links the cultural and political history of American war dead to explore the transatlantic and transpacific contexts of Americas imperial ambitions.Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019015608

ISBN 9781496201843 (cloth)

ISBN 9781496219091 (pdf)

ISBN 9781496219084 (mobi)

ISBN 9781496219077 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH : Collective memoryUnited States. | War and societyUnited StatesHistory. | War casualtiesSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory. | War memorialsSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory. | MemorializationUnited StatesHistory. | DeathSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC HM 1027. U 6 B 65 2020 | DDC 303.6/6dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019015608

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For Julie S. Bontrager (19492019) and Andrew R. Cumming (19442019), both of whom we lost too soon.

Contents

My grandfather, Benedict Bontrager, was born and baptized Amish, but he left the agrarian, anti-intellectual, moral life that his family lived, taking his wife and his children with him. Bens family shunned him when he left. The rejection of a first-born son and oldest sibling constituted a shocking rift within the family, but it also created a profound fissure between the past and the present, as they rarely spoke to Ben for the rest of his life. Their family life forevermore remained in the past while my grandfathers non-Amish life existed in the present. On occasion, memories of the past drifted into the present, but only momentarily. For example, when my grandmother, Mary Bontrager, died of cancer in the 1980s, many Amish Bontragers defied their bishops decree and attended her funeral alongside their ostracized brother in an illicit yet profound statement of sympathy. They didnt speak to him, however, beyond the customary condolences one utters over the dead. In essence the presence of my grandfathers Amish kin at my grandmothers funeral represented the flickering memory of a family long ago ripped asunder by a shunning.

I was born just days before the last U.S. combat troops left Vietnam in March 1973. This war separated the American past from the present in powerful ways. The dishonesty of politicians and the failures of military leadership produced a culture not only of concealing the truth from the American people but also of concealing the history of American empire. The consequences of these kinds of fissures were profound. I could feel this legacy of Vietnam growing up in St. Joseph County, Michigan, which had its fair share of Vietnam veterans who almost never talked about their experiences. Our neighbor served as a medic during the war, but that was about all he could bring himself to mention. Those who occasionally spoke sometimes broke down in fits of sadness. Some men I knew suffered from flashbacks and post-traumatic stress disorder ( PTSD ). Some never recovered from their trauma. While growing up, I saw the illness shockingly manifest itself on a few occasions as ghosts of memory returned to wounded men to haunt even the strongest of them. But despite living through debates about Agent Orange and the recovery of POW / MIA s, the anguish felt by these members of our community never directly touched my family. Most Amish people religiously opposed wars on the grounds that Jesus of Nazareth required his followers to turn the other cheek. Bens own grandfather and my great-great-grandfather, Manassas, were punished for this religious belief during the First World War. Manassas Bontrager, a bishop, wrote a letter that an Amish periodical published advocating that young Amish men should attempt to live the pacifist life of Christ and avoid military duty. He wrote this letter after Congress had passed the Sedition Act in 1918, and federal authorities quickly arrested him. He pled guilty and served jail time. The U.S. military developed Conscientious Objector ( CO ) protocols in earnest, in part, as a consequence of the many thousands of American Mennonite, Amish, and other religious followers who believed in their Christian duty to refuse to fight in the First World War. As evidence suggesting that shunning cannot completely separate the past from the present, I like to think that Manassass trial helped our family, as my own father claimed CO status in the 1960s when his draft number came up. My father passed his CO examination and served time working in a local hospital in lieu of military service. I grew up sad that some in our community suffered from their war experiences, yet I was thankful that my father never had to endure this trauma.

This gratitude did not shield me, however, from the chasm that separated me from my family and insulated me from the American past. I carved my own identity in the shadows of this post-shunning/post-Vietnam world. The shunning of my grandfather separated him from his brothers and sisters (and me from hundreds of kinfolk) while the conflict in Vietnam invigorated a culture of forgetting even when symptoms of PTSD or cancer from the use of Agent Orange signified to everyone just how traumatic the experiences of war continued to be. The lack of government transparency coupled with the publics unwillingness to critique the American empire robbed veterans of their ability to talk about the war. This separated people of my generation from the conflict and quarantined us from the past. While completing this project, I realized how my grandfathers shunning and the Vietnam War intersected within my own memory. My ability to make my individual identity depended on my association to a kinship network of which I was not a member while my social identity required access to a cultural memory that concealed the past from me. I had to work around these limitations by seeking out alternative networks that could help me recover the past more effectively. I am not alone in this labor. Millions of people have had to perform similar work, and although our individual memories and our own interpretations may be different, all of us have carved our identities from sharing our memories with others. To those in my family and those who endured the Vietnam conflict at home and on the battlefield, I owe a profound debt of gratitude.

Next page