ADVANCE PRAISE FOR FDRS GAMBIT

Laura Kalmans revisionist account of the court packing crisis of 1937 delves more widely and deeply into the relevant archival materials and contemporary journalistic coverage than has any previous treatment. Her overview of the vast body of scholarship concerning constitutional development in the New Deal period is erudite and discerning. Even those who may differ with her normative perspective or with some of her interpretive conclusions will find much to learn from and admire in this absorbing and illuminating narrative.

Barry Cushman, John P. Murphy Foundation Professor of Law, University of Notre Dame

Laura Kalman has been a longtime participant in and observer of the ongoing debate about the political and legal significance of the Roosevelt administrations introduction of a bill to expand the size of the Supreme Court in early 1937. This book is her most recent and extensive contribution to the debate. It demonstrates Kalmans great talent for archival research and exceptional command of scholarly literatures. Students of the New Deal, twentieth-century American politics, and twentieth-century constitutional history are in debt to Kalman for her illuminating intervention into a scholarly issue of enduring significance.

G. Edward White, David and Mary Harrison Distinguished Professor, University of Virginia School of Law

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780197539293

eISBN 9780197539316

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197539293.001.0001

For my legal historian friends and the archivists who sustain us

Contents

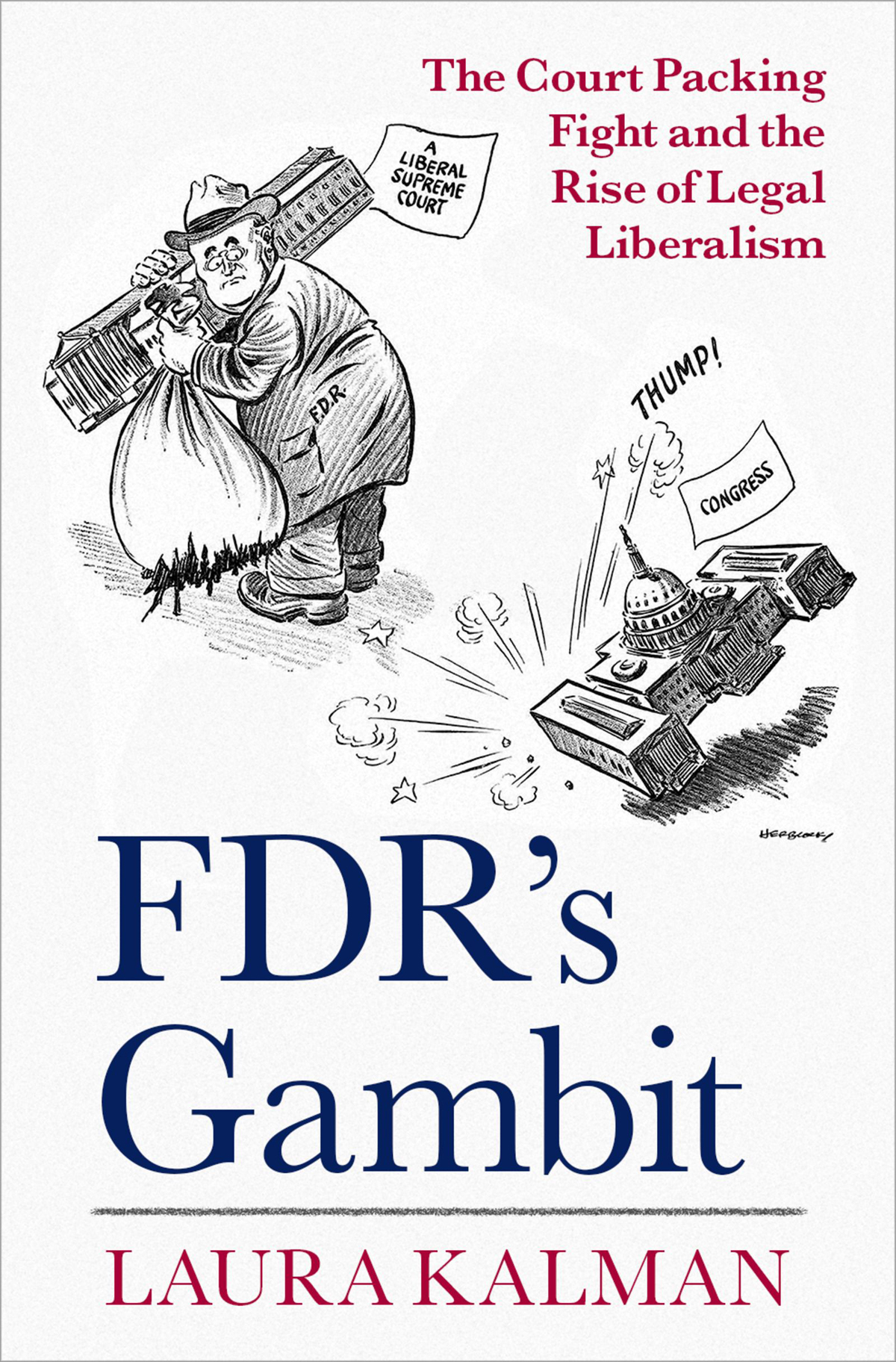

Court Packing as History and Memory

Open any US history text and you will find some version of the following story. During Franklin Roosevelts first term, a liberal president and Congress confronted the nine old men of the Supreme Court, most of whom waged war against the New Deals push to end the reign of conservative laissez-faire. The reactionary elderly justices in the majority struck down statute after statute, often by razor-thin margins. Then in November 1936, FDR won the greatest Electoral College victory since James Monroe. Flush with success, he introduced a bill the following February that would reorganize the judiciary and help out the overworked court by adding a new member for everyone who did not retire within six months of reaching the age of seventy, up to six additional justices. That rationalization deviously hid Roosevelts real motivation for the proposal: During his first term, he had not had one vacancy on the court, which housed six elderly justices, five of whom he believed remained to thwart economic recovery and social reform. A firestorm followed. Horrified Republicans and some Democrats accused the president of packing the court for ideological gain. When the court stunned the administration by handing down favorable decisions in the spring, some maintained that Roosevelt should back off because the justices had bent to his will. But he refused, and the fight continued. In July, 168 days after the battle had begun, the president lost it when the Senate recommitted his bill by seventy to twenty. The magnitude of his failure made his bill look exceptionally foolish.

Ever since Joseph Alsop and Turner Catledges 1938 instant history, The 168 Days, calcified the way it was remembered, the court fight has been portrayed as the doomed, idiotic brainchild of an arrogant FDR. Just consider a few characterizations. According to Kenneth Davis, the president suffered from the pride that goeth before a fall after his re-election and before he made his tragic error, which was then compounded by a stubborn persistence in it. William

And with what positive result? Some do suggest that Roosevelts threat to enlarge the court caused one or two conservative justices to join with the liberals in upholding key New Deal legislation, though scholars debate when the switch in time that saved nine occurred and the reasons for it. Yet they nearly universally portray Roosevelt as a nodding and arrogant Homer, his failure as a victory for common sense, his scheme as destined for defeat. Consequently, according to two law professors, In the near century since, court-packing has been treated as a political third railmaking the Courts current size look like an entrenched, quasiconstitutional norm. And when proposals to change the courts size began circulating anew as Democrats confronted another court they feared, some echoed the shock and horror of Roosevelts foes, while others argued that if a politician of FDRs vaunted wizardry with his congressional majorities couldnt pull off changing the courts size, no one could. The way we remembered events became a club to wield against change.

But the history of the court fight sends a different message. In this book, I challenge the conventional wisdom. I aim to show that hubris did not explain Roosevelts actions. He was displaying the same shrewdness that enabled him to win a massive 1936 re-election victory despite the best efforts of an antagonistic press and angry elites. Further, on almost every day he battled with Congress and the court, he could reasonably anticipate achieving some success in the form of additional justices and for the principle of court enlargementas all, including the justices, were very well aware. Whether or not it is the right remedy for todays troubles, court packing does not deserve to be recalled as one fated for failure in 1937.

To see that, we must follow events as they unfolded, without the distortions of hindsight. Instead of recounting the story from the usual perspective of how it turned out and as an inevitable defeat, I tell one of possible victory. The Supreme

behalf of the disadvantaged and dissidents, and how the clash has resonated in subsequent discussions of court packing. Instead of wondering why the topic looms over contemporary national debate, it suggests, we should marvel that the enduring strength of the flawed memory of court packing as an ill-fated and indefensible remedy for 1937 prevented its reemergence sooner.

I must have learned about the court fight in high school, college, or law school, but the first time I remember doing so was in a lecture by my beloved dissertation adviser, John Morton Blum. Once I happened on William E. Leuchtenburgs work, I was hooked.