First published 1978 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1978 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 76-1777

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Siegal, Harvey A.

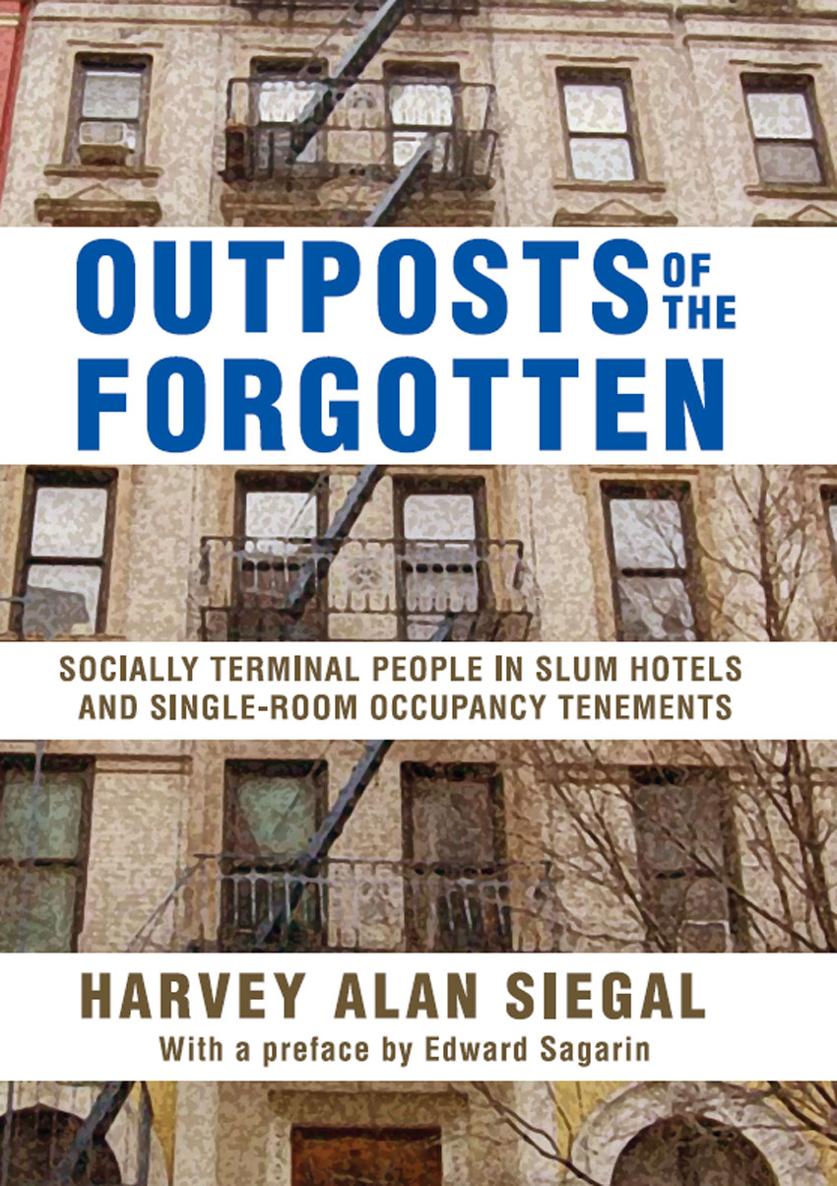

Outposts of the forgotten.

Bibliography: p.

ISBN 0-87855-141-7

Includes index.

1. New York (CityPoorCase studies. 2. New York (City)Lodging-houses. 3. Alienation (Social psychology)Case studies. I. Title.

HV4046.N6S53 362.5 | 76-1777 |

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-5468-9 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-89855-141-5 (hbk)

Nostalgia is almost by definition a joyous experience. For many of us, the past is romanticized, its blemishes overlooked or underplayed, and perhaps we see it in a different light because we were younger, probably healthier, and had the world before us. We were certain that, if we did not conquer we would at least improve it, although it did not cry out so much for improvement as did the world that we will leave our own children and grandchildren. So it is when I recall that once the letters S.R.O. meant, for New Yorkers particularly as we lived in the theatrical capital of the world, but for Americans elsewhere as well, that a theatrical or cinematic performance had standing room only. And stand we did, sometimes paying as much as fifty-five cents for the privilege, but without fear that our pockets would be picked. Disappointed as we were not to be able to obtain seats in which we could relax while we admired, we were nonetheless elated to be part of an era of such cultural vibrancy.

Now, in an irony if not a coincidence, S.R.O. has come to have new meaning: the initials stand for single room occupancy, a type of housing that existed in previous generations but that has proliferated, and for which residents in some instances, social service agencies in others, are paying exorbitant prices to exploitative landlords, protected by a combination of indifference if not hostility to these residents by others in the world around them, by corruption, bureaucratic entanglements, and the powerlessness of the poor and the wretched.

It is a world today, particularly in the urban areas, that has more than did previous decades of the lonely, the wretched, and the desperate: the flotsam and jetsam who are societys rejects and discards. For some, we move them off to small enclaves, out on an island where they will not be eyesores to the good people, or off to a small town hundreds of miles from what little family relationships they had had, where they might just as well be exiled to a Devils Island, so formidable are the distances and so expensive a visit. Others are huddled into ghettoes, hospitals and asylums (what an irony, to use the word asylum, with its connotation of a haven of freedom, for a place where one is locked up), stigmatized, and largely forgotten and finally, with an ability to look without seeing, to listen without hearing, we allow some of these persons to live in our midst, on our busiest streets, only next door to or down the block from a world of normal and respectables, yet we manage to ignore their presence. These include the denizens of single room occupancy hotels, and as Harvey Siegal has so magnificently captured in his title, these are the outposts of the forgotten. Yet not quite, for so long as one young sociologist, one young man motivated by a thirst for knowledge and by a suspicion that he would encounter people in desperate need of understanding, compassion, and advocacy, they are not forgotten. Hopefully, in the very title of his work and in the pages that follow, Siegal may have produced a self-defeating prophesy.

There are many ways of presenting a vision of life, and each has values that recommend it. The novelist, on the rare occasion that a novelist would look at the people who are Siegals S.R.O.ers (for the muckraking novelist seems to have lost favor in American and world letters, his day is over, and few of his works have survived him)such a writer creates fictional characters and situations to delineate a world whose reality is inescapable. The journalist calls attention to social evils and reaches large numbers of readers, but interest flags and lags, and within a few days something new is holding the attention of the newspaper world. The psychologist will give us case histories, again on the rare occasions that he would even turn attention to such persons; they would have to be accused of serious crime, and bizarre crime at that, before becoming a case history for a psychologist, and as for psychological study of what living under such conditions does to an individual, we can imagine the worst, but of science we have nothing. So that while the social workers go about their tasks, difficult, frustrating, sometimes becoming as demoralized as the clients themselvesalthough always with the mental reservation that they will return to a better or at least a more comfortable world when the working day has endedit remains for the sociologist to look at what is indisputably a far from pretty part of our urban scene.

This was a challenging risk, an important one, but in many ways unattractive, hardly beckoning to one who had grown up among the niceties of an upwardly mobile but nonetheless lower-middle-class urban life, and who had just emerged from the ivy but not ivory towers of Yale University. It would have been somewhat more pleasant, but at the same time barely worth the effort of a brilliant mind that was already fulfilling its early promise, to send out questionnaires, or even go personally and get them answered, all the right boxes filled in, each question worded in a careful manner according to all of the methodological rules, and then have the answers coded, the data computerized, and the information spread out on hundreds of tables, with the statistical significance of countless correlationsand all the rest of the meaningless claptrap and quantitative humbug that fills our journals and passes for social science.

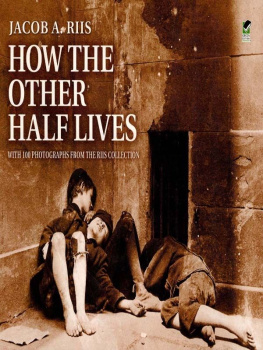

Harvey Siegal was not the first to have chosen the difficult path of living with the people he was studying, working in various capacities for and with them, participating in as full a sense of the word, while observing, as it is possible to participate when one knows that there will be an end to the research and that he will abandon a world which holds these others as tightly as if it were a prison. It is a magnificent tradition in sociology that he followed, a tradition that has given us glimpses of the world of hobos, petty criminals, organization bureaucrats, slum dwellers, poor corner boys, and skid row alcoholics, among others. Yet, of all of these and numerous others that could be added, it is doubtful if any sociologist has ventured forth and successfully penetrated into a wold from which he was removed by greater social distance than did Harvey Siegal when he entered S.R.O. tenements and slum hotels.