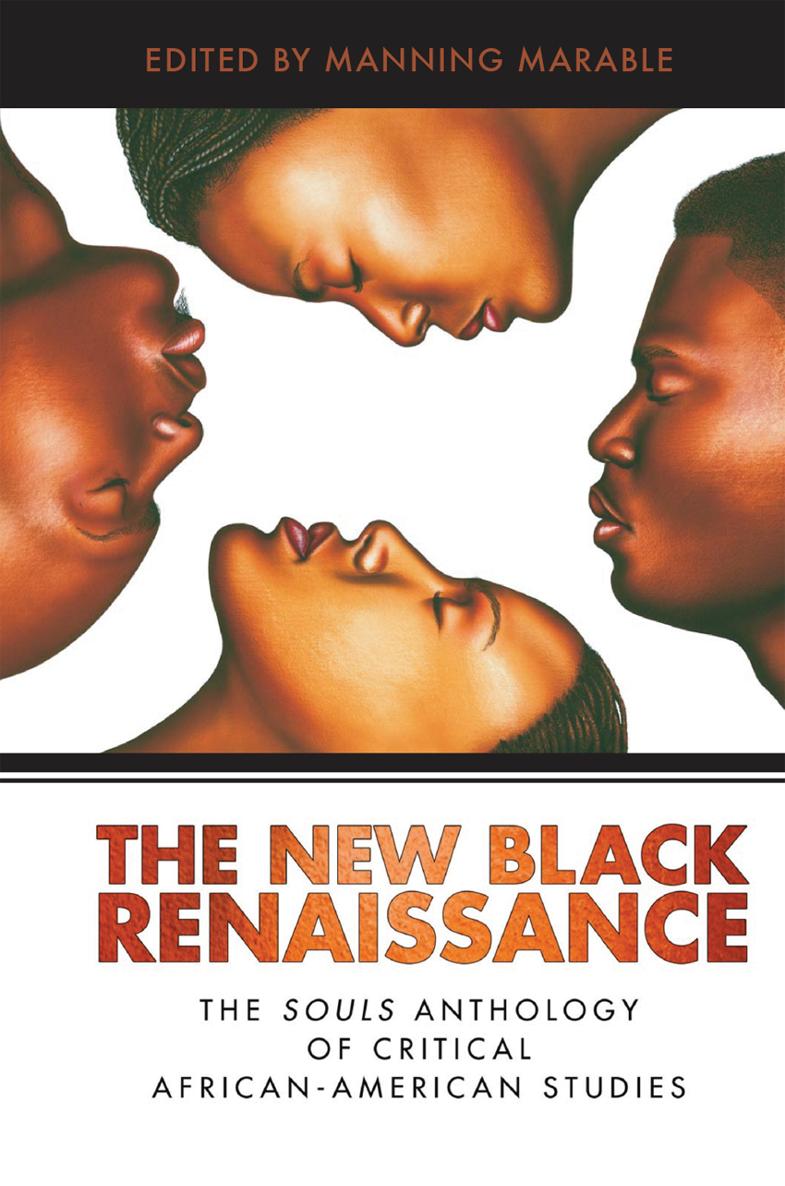

The New Black Renaissance

The New Black Renaissance

The Souls Anthology of Critical African-American Studies

Edited by

MANNING MARABLE

Professor of Public Affairs, History, and African-American Studies

Director, Center for Contemporary Black History

Columbia University

Associate Editors

KHARY JONES

PATRICIA G. LESPINASSE

ADINA POPESCU

First published 2005 by Paradigm Publishers

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2005 Manning Marable

All articles contained in this book, with the exception of Living Black History by Manning Marable and Losing Ground by Leith Mullings (which are copyright the authors) are copyright the Trustees of Columbia University. The articles were previously published in the journal Souls by the Center for Contemporary Black History at Columbia University.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The new Black renaissance : the Souls anthology of critical African-American studies / edited by Manning Marable ; associate editors Khary Jones, Patricia G. Lespinasse, Adina Popescu.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-59451-141-1 (hc) ISBN 978-1-59451-142-4 (pbk)

1. African AmericansStudy and teaching. 2. African AmericansIntellectual life. 3. African AmericansPolitics and government. 4. African AmericansSocial conditions1975- 5. Afrocentrism. 6. Transnationalism. 7. EthnicityUnited States. 8. MulticulturalismUnited States. 9. United StatesRace relations. 10. United StatesSocial policy1993- I. Marable, Manning, 1950-

E184.7.N48 2005

308.896073dc22

2005012208

Designed and Typeset by Cheryl Hoffman

ISBN 13 : 978-1-59451-142-4 (pbk)

Contents

, Manning Marable

, Manning Marable

, Howard Winant

, Herbert Aptheker

, Jeffrey R. Kerr-Ritchie

, Robin D. G. Kelley and Betsy Esch

, Leith Mullings

, John L. Jackson Jr.

, George Derek Musgrove

, Nikhil Singh

, Gary Y. Okihiro

, Michael Awkward

, Barbara Smith

, Dana-Ain Davis, Ana Aparicio, Audrey Jacobs, Akemi Kochiyama, Leith Mullings, Andrea Queeley, and Beverly Thompson

, Daphne A. Brooks

, Andrea Queeley

Todd Boyd

, Lee D. Baker

, Noel Ignatiev

, Eric Klinenberg

, David Roediger

, John Hartigan, Jr.

, Tim Wise

, Karen Brodkin

, Assata Shakur

, Bill Fletcher Jr.

, Julia Sudbury

Hishaam D. Aidi

, Farah Jasmine Griffin

, Hazel V. Carby

, Kathleen Neal Cleaver

, Clayborne Carson

Because of the reality back of it, we continue the use of the older concept of the word race, referring to the greater groups of humankind, which by outer pressure and inner cohesiveness, still form and have long formed a stronger or weaker unit of thought and action. Among these groups appear both biological and psychological likenesses, although we believe that these aspects have in the past been overemphasized in the face of many contradictory facts. While, therefore, we continue to study and measure all human differences, we seem to see the basis of real and practical racial units in culture. We use then the old word in new containers. A culture consists of the ideas, habits, and values, the technical processes and goods, which any group becomes possessed of either by inheritance or adoption.

Looking over the world today we see as incentive to economic gain, as cause of war, and as infinite source of cultural inspiration nothing so important as race and group contact. Here if anywhere the leadership of science is demanded not to obliterate all race and group distinctions, but to know and study them, to see and appreciate them at their true values, to emphasize the use and place of human differences as tool and method of progress; to make straight the path to a common world humanity through the development of cultural gifts to their highest possibilities. A new view of the social sciences is necessary, as comprehending the actions of men and reducing them to systematic study and understanding. In this way we foresee a reinterpretation of history, education, and sociology; a rewriting of history from the ideological and economic point of view.1

W. E. B. Du Bois, 1940

In 1906 at Columbia University in New York, South African student Pixley KaIsaka Seme gave a stirring lecture, The Regeneration of Africa, upon which the university bestowed its most prestigious prize for oratory. In the talk, Seme declared that the people of Africa were prepared for a new realization of their capacity for redefining their destinies: the ancestral greatness, the unimpaired genius, and the recuperative power of the race, its irrepressibility, which assures its permanence, constitute the Africans greatest source of inspiration. The regeneration of Africa means a new and unique civilization is soon to be added to the world.2 After completing his law degree at Columbia, Seme was admitted to the bar at Londons Middle Temple, returned to South Africa in 1910, and in 1912 became cofounder of the protest organization that would later become the African National Congress (ANC). For Seme, an African regeneration or renaissance had embedded within it the concepts of black consciousness, a challenge to European hegemony, and the popular reawakening of the African people.

For Seme, John Langalibalele Dube, and other African intellectuals who founded the ANC, the concept of an African or black renaissance was an attempt at renegotiating the relationship between the black world and European domination, political as well as cultural and ideological. Embedded in this concept as well was the recognition that people of African descent now lived in new contexts as a result of the consolidation of European direct rule throughout most of the African continent in the late nineteenth century. Black intellectual and cultural production aimed at subverting European power over blacks lives soon dovetailed with the concept of black renaissance.

In the century since Semes oration, the concept of a black or African renaissance has been popularized throughout the African diaspora and on the African continent as well. In 1937, Nigerian nationalist Nnamdi Azikiwe had predicted this emergence in his book