About the author

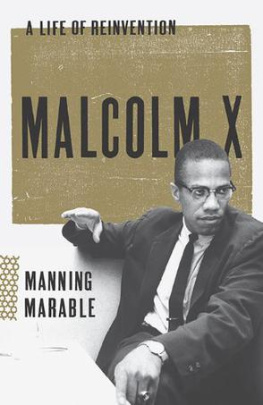

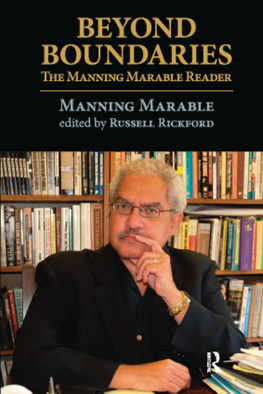

Manning Marable (19502011) was a professor of history, public affairs, and African-American Studies at Columbia University. Marable authored fifteen books including Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention , for which he won the Pulitzer Prize for History.

Leith Mullings is a distinguished professor of anthropology at the Graduate Center CUNY. She is an anthropologist, author, lecturer and educator. Her Web site is http://leithmullings.com.

CHAPTER ONE

THE CRISIS OF THE BLACK WORKING CLASS

So long as white labor must compete with black labor, it must approximate black labor conditionslong hours, small wages, child labor, labor of women, and even peonage. Moreover it can raise itself above black labor only by a legalized caste system which will cut off competition and this is what the South is straining every nerve to create... It is only a question of time when white working men and black working men will see their common cause against the aggressions of exploiting capitalists.

W. E. B. Du Bois, The Economic Revolution in the South, in B.T. Washington and DuBois, The Negro in the South (London: Moring, 1907), pp. 114-115, 117.

Unless organized labor transforms itself into a social movement with broad goals and a new concept of union membership that goes beyond dues-payers in a collective bargaining unit, it will continue its current decline. And if it is transformed, the character of a new dynamic labor movement will be expressed most significantly in its active and special concern for the problems of racial minorities and women at the work place and in the community.

Herbert Hill, The AFL-CIO and the Black Worker, Journal of Intergroup Relations, Vol. 10 (Spring, 1982), pp. 5-78.

I

The central character and participant of Black U.S. history is the Afro-American. This is not a particularly surprising statement: the central focus of Irish history is the Irish people; Japanese history examines the people of Japan, and so forth. Yet there is a hidden problematic here for the political economist. The presumption here is that the people share a common social history, a collective experience, and perhaps even a collective consciousness. This is the first assumption that must be challenged.

Black people in the U.S. are the direct product of massive economic and social forces which, at a certain historical juncture, forced the creation of the early capitalist overseas production of staples (rice, sugar, cotton) for consumption by the Western core. The motor of modern capitalist world accumulation was driven by the labor power of Afro-American slaves. In the proverbial bowels of the capitalist leviathan, the slaves forged a new world culture that was in its origin African, but in its creative forms, something entirely new. The Afro-American agricultural worker was one of the worlds first proletarians, in the construction of his/her culture, social structures, labor and world view. But from the first generation of this new national minority group in America, there was a clear division in that world view. The Black majority were those Afro-Americans who experienced and hated the lash; who labored in the cane fields of the Carolina coast; who detested the daily exploitation of their parents, spouses and children; who dreamed or plotted their flight to freedom, their passage across the River Jordan; who understood that their masters political system of bourgeois democracy was a lie; who endeavored to struggle for land and education, once the chains of chattel slavery were smashed; who took pride in their African heritage, their Black skin, their uniquely rhythmic language and culture, their special love of God. There was, simultaneously, a Black elite, that was also a product of that disruptive social and material process. The elite was a privileged social stratum, who were often distinguished by color and caste; who praised the master publicly if not privately; who fashioned its religious rituals, educational norms, and social structures on those of the West; who sought to accumulate petty amounts of capital at the expense of their Black sisters and brothers; whose dream of freedom was one of acceptance into the inner sanctum of white economic and political power. Both the Black majority and the Black elite were often divided by language, politics, economic interests, education and religion. That both groups were racially Black escaped no ones attention, least of all the white authorities. Yet both had created two divergent and often contradictory levels of consciousness, which represented two very different kinds of uneven historical experiences.

Malcolm X, the greatest Black revolutionary of the 1960s, recognized the essential conflict in the history and class consciousness of Afro-America. Speaking before civil rights activists in Selma, Alabama, only three weeks before his assassination, Malcolm characterized this pivotal contradiction as the division between the house and field Negroes:

The house Negro always looked out for his master. When the field Negroes got too much out of line, he held them back in check. He put them back on the plantation. The house Negro lived better than the field Negro. He ate better, he dressed better, and he lived in a better house. He ate the same food as his master and wore his same clothes. And he could talk just like his mastergood diction. And he loved his master more than his master loved himself. If the master got hurt, hed say: Whats the matter, boss, we sick? When the masters house caught afire, hed try and put out the fire. He didnt want his masters house burnt. He never wanted his masters property threatened. And he was more defensive of it than his master was. That was the house Negro.

But then you had some field Negroes, who lived in huts, had nothing to lose. They wore the worst kind of clothes. They ate the worst food. And they caught hell. They felt the sting of the lash. They hated this land. If the master got sick, theyd pray that the masterd die. If the masters house caught afire, theyd pray for a strong wind to come along. This was the difference between the two. And today you still have house Negroes and field Negroes.

Historians might disagree with Malcolms portrait of the plantation, pointing out that most slaves worked on farms with fewer than twenty Blacks. There were relatively few large plantations in the United States that were comparable to those of pre-revolutionary San Domingue, Bahia or Pernambuco, and the actual social and material conditions which usually separated Black house servants from field hands in the U.S. experience were insignificant. Yet the strength of Malcolms commentary is essentially ideological and political. The embryonic Black elite was the product of the enslavement process, those New World Africans who culturally assimilated the world view of their exploiters. Resistance tended to come from those who had suffered the most, physically and mentally, at the hands of the masters. Some slaves docilely accepted their plight; others did not.

The Black majority was confronted with two decisive political options which, as we shall explore later, form the crucial axis of Black history: resistance and accommodation. Slavery and colonialism created the material conditions which forced an oppressed people to leave the surroundings of their previous history. That is, the external constraints demanded by coerced labor and a rigid caste/social hierarchy redirect the forces of a peoples history. The slave could not live for him/herself at any particular moment during the productive process; the slave was viewed by the master as a cog in the accumulation of capital. Many slaves responded to the daily exploitation of the work place by resistingrunning away, destroying machinery, burning crops, killing the master and his family. Others protested in more subtle ways, such as work slowdowns. But all faced the inevitable wall of reality from which there was no real escape. Rape, murder and the terrorization of their communities would continue as a logical and necessary part of capitalist society. One could stand against the weight of the exploiters history, and suffer the inevitable concequences. Many chose to die this way. But the path of resistance contained no guarantees that ones lover, spouse, parents or children would escape brutal retribution for ones act of glorious defiance. One could make ones own history, but no single act of protest would overturn the powerful machinery of the racist/capitalist state, unless that action took a collective form involving others. Institutional safeguards usually blocked this option of mass-based resistance.

Next page