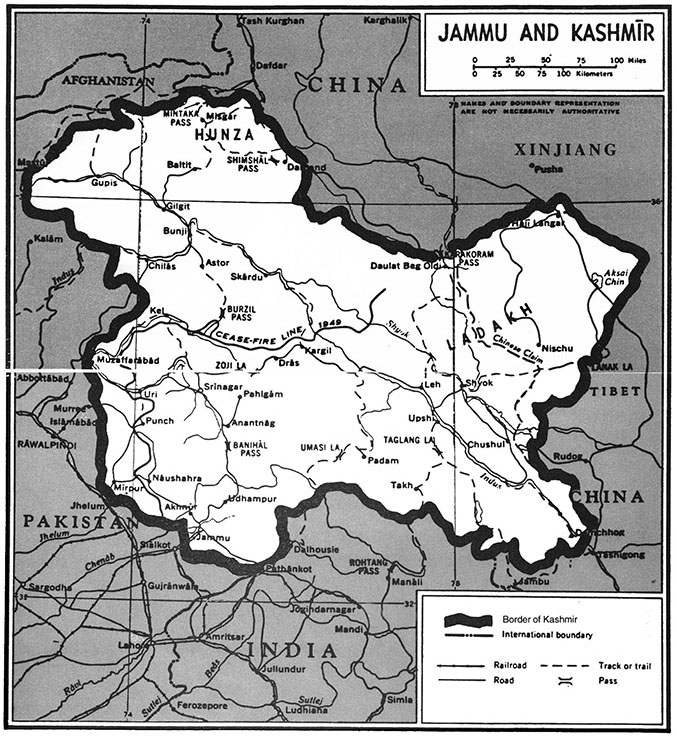

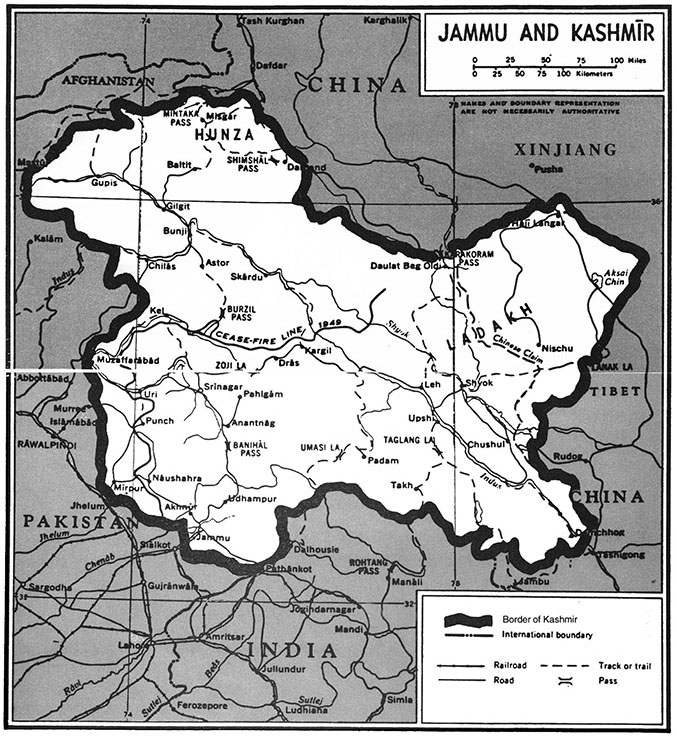

Map 1: Jammu and Kashmir

The Kashmir Tangle

The Kashmir Tangle

Issues and Options

Rajesh Kadian

First published 1993 by Westview Press, Inc.

Published 2019 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1993 by Rajesh Kadian

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kadian, Rajesh.

The Kashmir tangle : issues and options / by Rajesh Kadian.

p. cm.

Originally published: New Delhi : Vision Books, 1992.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8133-8767-1

1. Jammu and Kashmir (India)Politics and government. I. Title.

DS485.K27K32 1993

954'.605dc20

93-13715

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-29339-0 (hbk)

Contents

Maps

- Jammu and Kashmir

Photographs (photos follow page 96)

In June 1992 the Bush administration stated that the Kashmir imbroglio needed "an outside perspective [because Indians and Pakistanis] are locked in a mindless competition over tactical advantage and scoring diplomatic points." About six months later, President Ginton in his inaugural address declared, "Today, as an old order passes, the new world is more free but less stable. Communism's collapse has called forth old animosities and new dangers. Clearly America must continue to lead the world." Among the old animosities is the Kashmir dispute. This book attempts a concise, holistic appraisal of the issues and options in Kashmir.

For simplicity, I have used Kashmir when referring to the erstwhile Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir- similarly, the Muslim League for the All India Muslim League and the Congress Party for the Indian National Congress and its direct successor, the Congress(I).

Diverse, sometimes contradictory, inputs from people in different walks of life have gone into this book. Since the vast majority of them are still active I have chosen to maintain their collective anonymity. Nevertheless, I take this opportunity to thank all of them.

I am once again deeply indebted to the United Service Institution of India, New Delhi, and the Combined Arms Research Library at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for their continued assistance. I am also grateful to both my publishers, Vision Books (Pvt.) Limited, New Delhi, and Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado, for maintaining fine standards of professionalism.

I close by reminding myself of the observations of a distinguished British historian who was no stranger to the Indian Subcontinent. Micheal Edwardes wrote in The Last Years of British India:

"The writing of contemporary history is always difficult. Much of the real material of such history is not, at least officially, available to the historian. There is also the question of how truthful one's informants are."

RAJESH KADIAN

1

A Parting of Illusions

In November 1989 India was in the throes of a general election. The ruling Congress(I) Party was widely viewed as slipping out of power. In its wake the Janata Dal coalition was faying to pick up enough pieces to offer a viable alternative government. On the other hand the rejuvenated right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party also sensed a historic opportunity for growth. With the stakes being so high, the tempo of political activity was frantic all over India. In stark contrast lay the breathtakingly beautiful vale of Kashmir. No garish posters, colourful banners or raucous party rallies disturbed the enchantment of the near-deserted valley on the threshold of winter. Neither the end of the tourist season nor sublime considerations to preserve the natural beauty of the place accounted for the stillness in Kashmir. Instead, the reason was simply a clear call by shadowy militant organisations asking for the boycott of the elections. Unmindful of these calls, the largest regional party, the Jammu and Kashmir National Conference, put up a candidate each for the three Lok Sabha seats from the valley. Not unexpectedly all three won uncontested.

Elsewhere, the elections accompanied by unprecedented violence, saw the Congress(I) lose its majority in the Lok Sabha but retain its standing as the largest single parliamentary party with 194 seats. The Janata Dal with 142 MPs constituted the second largest party and formed a minority government with majority outside support from the Bhartiya Janata Party and the two Communist parties.

In the new government a lightweight politician, Mufti Mohammed Sayeed was unexpectedly nominated as the nation's first Muslim Home Minister. Though a Kashmiri, he was elected from Muzaffarnagar in U.P. Though he failed to represent his home state in the Indian parliament, an event there was soon to engulf him. For while the Mufti was holding his first meeting with the officials of his new ministry on the afternoon of 8 December 1989, a more dramatic event was taking place in Srinagar. On that fateful afternoon, the Mufti's daughter, Dr. Rubaiya, was on her way home after a busy morning at the Lalded Memorial Women's Hospital where she was an intern. Rubaiya boarded the local transit van, a green Matador. The vehicle was waylaid by four armed men, who at gunpoint bundled Rubaiya into a Maruti car and sped away. Two hours later the kidnappers telephoned the local newspaper, The Kashmir Times, and communicated their demands: the release of five Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) militants in government custody.

By that evening the machinery of state had swung into action under Arun Nehru. This portly cousin of the former Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi, had briefly served as the Minister of State for National Security under the previous government. After the 1989 election he became the Tourism and Commerce Minister in the new administration but found himself once again handling national security matters because of this abduction. Two days later two senior Ministers from the Central Government, Arif Mohammed Khan and Inder Kumar Gujral flew to Srinagar to make an assessment of the situation. Neither the agency charged with domestic surveillance, the Intelligence Bureau (IB), nor the organisation in charge of overseas operations, the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) could provide any leads; not even the names of possible mediators with a clout with the militants. No hard information was available about either the kidnappers or their possible hideouts. Also, little data was obtainable from the intelligence wing of the Border Security Force (BSF) or from Military Intelligence (MI). Likewise, similar agencies of the State Government were of little help. In New Delhi the elite National Security Guards (NSG) volunteered to go into action with such minimal information as the broad geographical area where Rubaiya might be held hostage. But the Mufti refused this help with alacrity. Instead he prodded the State Government to meet the demands of the militants.