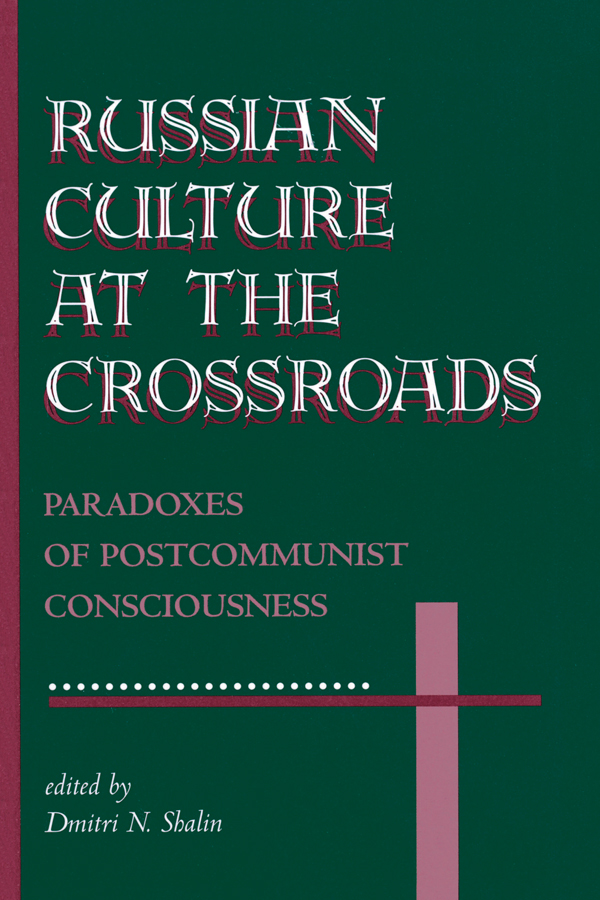

Russian Culture at the Crossroads

First published 1996 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1996 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Russian culture at the crossroads : paradoxes of postcommunist

consciousness / edited by Dmitiri N. Shalin

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8133-2713-X. ISBN 0-8133-2714-8 (pbk.)

1. Russia (Federation)Civilization20th century. 2. Post-

communismRussia (Federation) I. Shalin, Dmitri N.

DK510.762.R87 1996

306.0947dc20

95-46271

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-0-8133-2714-3 (pbk)

To My Russian Colleagues and Friends

Contents

, Dmitri N. Shalin

, Boris M. Paramonov

, Dmitri N. Shalin

, Alexander M. Etkind

, Jerry G. Pankhurst

, Svetlana Boym

, Igor S. Kon

, Zara Abdullaeva

, Maurice Friedberg

, Daniil B. Dondurei

, Vladimir S. Magun

, Yuri A. Levada

, Frederick Starr

, Bruce Mazlish

Guide

A few words about those who helped make this study possible are in order here. I wish to thank the Harvard University Russian Research Center for a research fellowship that allowed me to spend my 198990 sabbatical year at the Center and afforded many a fruitful encounter with its members, whose advice and friendly criticism helped get this project off the ground. Special thanks are extended to the MacArthur Foundation for a grant that made the Russian participants visit to the United States possible. We owe a debt of gratitude to the International Research and Exchanges Board, the George Soros Foundation, the Nevada Humanities Committee, the UNLV Foundation, UNLV College of Business and Administration, and the Jewish Federation of Las Vegas, which provided partial support for the Nevada Conference on Soviet Culture. Several Las Vegas businessesthe Tropicana Hotel, the Vista Group, Nevada Gaming, Inc., Aztec Gas and Oil, United Gaming, Inc., and First Interstate Bankpitched in with local accommodations for conference participants. The contribution of Lonnie Hammargren, who graciously greeted the conference participants at his home, is also gratefully acknowledged. The help from the business community for a strictly academic enterprise is highly appreciated, particularly at a time when federal funding sources for such international projects have dwindled.

Dr. Yuri Levada, director of the National Center for Public Opinion Research in Russia, and Dr. Vladimir Yadov, director of the Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of Sociology, helped facilitate the project on the Russian side and accommodated American participants visiting Russia. I thank Vladimir Magun, Daniil Dondurei, Zara Abdullaeva, Alexander Etkind, and Igor Kon, who helped me personally to navigate through the Russian bureaucracy and engaged me in numerous conversations that gave the project its present shape.

Finally, I wish to thank my wife, Dr. Janet S. Belcove-Shalin, for selflessly aiding in the work and putting up with the temporary insanity that several years of writing proposals, organizing conferences, translating Russian texts, and editing the manuscript in its numerous incarnations might have induced in her husband. I owe her a debt that could never be repaid in any coin.

Dmitri N. Shalin

DMITRI N. SHALIN

This project on Russian culture goes back to the spring of 1990, when several American and Russian scholars met at the Russian Research Center at Harvard University and decided to join forces in a study of the changes sweeping the Soviet Union. From the start, the participants agreed that they would not try to chase fast breaking news from Russiaa hopeless task, given the pace of recent changesbut rather would focus on the continuity and change in Russian culture, on the long-term social forces that compel the Russian people to reexamine their values and reevaluate old ways.

We divided the labor so that each participant could explore a single cultural domainreligious, artistic, intellectual, political, economic, and so on. The borders demarcating each domain are not sharp, and the map of Russian culture we have drawn is admittedly arbitrary; but our survey is comprehensive enough to give the reader some insight into Russian culture, the key junctures in its historical development, and the momentous transformations it has been undergoing in recent years.

Our interdisciplinary project drew on the resources of both the humanities and the social sciences, which allowed for a cross-pollination of ideas. Our team of authors included historians, philosophers, psychologists, sociologists, political scientists, and literary and film critics. The participants used a wide range of methods to explore their subjects, including personal interviews, analysis of Soviet literature, film, and fine arts, and opinion surveys. We proceeded on the assumptions that humanists and social scientists can learn much from each other, that sociological surveys illuminate relationships crying out for fresh interpretations, and that humanistic insights open new vistas inviting further sociological probing.

Scholars working on this project met in Las Vegas, Nevada, on November 1920, 1992, for the Nevada Conference on Soviet Culture. Here, intellectuals raised in vastly different cultures reflected on their biases, enriched each others perspectives, and set up a framework for future collaboration. We plan to follow up this study with three more conferences and volumes, which will explore in greater depth the artistic, political, and economic realms in Russian culture. Meanwhile, we offer the first results of our joint efforts to our colleagues, students, and the general public with an interest in Russias past, present, and future.

The remainder of this introductory chapter focuses on several sticky methodological issues and substantive difficulties facing students of culture in general and Russian culture in particular. This is not an attempt to settle the problems vexing cultural studies but rather an effort to spell out assumptions undergirding our collective undertaking.

* * *

The vast literature on Russia has numerous references to culture. Each time this term is invoked, it acquires a somewhat different meaning, depending on whether the researcher is dealing with Russian culture, Bolshevik culture, Soviet culture, post-Soviet culture, and so on. In the broadest sense, the term refers to an enduring configuration of thoughts, actions, and institutions that distinguishes people inhabiting a given sociohistorical niche. Yet, there is always some ambiguity involved in the rhetoric of culture as to how enduring the pattern in question is, how much local diversity it allows, and how far a given variation has to stray from the main theme before it becomes a cultural theme in its own right. There is also a nagging concern that the values and beliefs people express verbally do not always match the preferences and commitments they reveal in their conduct. Finally, it is not altogether clear whether high cultureliterature, theology, political critique, philosophical treatises, and other highly stylized forms of public discoursegive us a reliable insight into the behaviors and lifestyles of society at large, especially when it comes to groups that do not consume high culture and are more attuned to popular culture.