This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47404-3797 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

2012 by Bruce Whitehouse

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

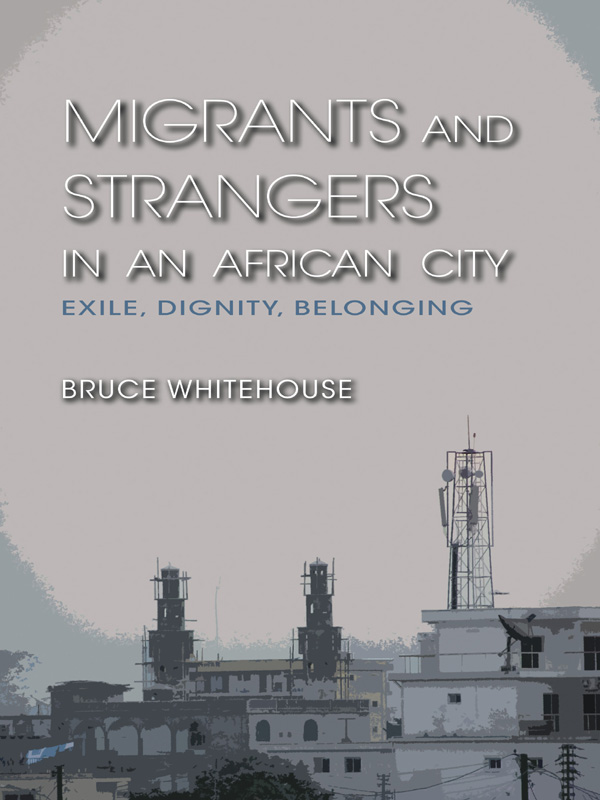

Whitehouse, Bruce, [date]

Migrants and strangers in an African city /

Bruce Whitehouse.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and

index.

ISBN 978-0-253-00081-1 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-253-00082-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-253-00075-0 (electronic book) 1. Congo (Brazzaville)Emigration and immigrationHistory. 2. West AfricansCongo (Brazzaville)Social conditions. 3. Congo (Brazzaville)Commerce. 4. Congo (Brazzaville)Religion. 5. TransnationalismSocial aspects. I. Title.

JV9016.5.W84 2012

305.896'606724dc23

2011040330

1 2 3 4 5 17 16 15 14 13 12

Acknowledgments

The cover of a book like this one often contains a fundamental falsehood: the notion that the author is single-handedly responsible for having dreamed up and expressed the ideas recounted within. I never appreciated the fallacy of this notion as much as upon the publication of Migrants and Strangers in an African City. This book is actually the product of many people, and as their names cannot appear on the cover I need to recognize their contributions here.

In Mali I have had the kindest of hosts, whose graciousness and guidance have been an essential aspect of my research over the years. The family of Mohammed Tour and Nana Keita Tour has welcomed me into their home and their lives, and has made my trips to Bamako both possible and pleasant. The extended family of the late Makansir Dram, of Missira, Bamako, has provided enlightenment and support both in the city and in their hometown. This project would never even have begun without them.

In the Republic of Congo I relied on a large network of individuals, both Congolese and foreign, who lent me their time, their words, and their wisdom. Because of the frequently sensitive nature of my research topic there, I cannot thank them by name. I am especially indebted to several faculty members of Marien Ngouabi University and the staff of the Consulate-General of Mali in Brazzaville. Moreover, I depended heavily on the willingness of the city's inhabitants to sit down with my wife or me and answer our questions. Every person who granted us an interview has shaped my outlook, and I hope that in giving them voice in these pages I have done justice to their views.

In the United States numerous people helped sharpen my understanding of transnationalism, globalization, and identity, from the West African migrants I once frequented in New York City to the faculty at Brown University where I completed my doctoral studies. At Brown's Department of Anthropology, David Kertzer, Dan Smith, and Nicholas Townsend read early chapter drafts and supplied invaluable feedback. I have been most fortunate to have Dan as my mentor. Matilde Andrade, Kathy Grimaldi, and Marjorie Sugrue always made sure I got what I needed. The Population Studies and Training Center (PSTC) at Brown provided me with numerous opportunities to discuss my findings and exchange ideas with fellow students and faculty members, especially during my postdoctoral year there working with Marida Hollos. I received vital assistance from the PSTC's Tom Alarie and Kelley Smith. Judy Lasker, chair of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Lehigh University, read a manuscript of this book and gave insightful comments. In 2009 I had the occasion to present my concluding chapter to a gathering of the African Seminar at Johns Hopkins University, where faculty members and students challenged me to rethink some of my basic assumptions. Lastly, two anonymous reviewers pointed out many mistakes and omissions in my earlier manuscript. All of their contributions have made this a better book.

In cyberspace, two virtual communities have constituted a wealth of information for my research. The cyber-diaspora emanating from Mali, especially as represented by the online forum Malilink, helped me follow events in that country from afar, sound out ideas, and check facts. The Congolese cyber-diaspora, as embodied by user forums on Congopage.com and Mwinda.org, served a similar purpose.

While I am grateful for the input of all those mentioned above, in some cases (and not always for the right reasons) I have chosen to ignore it. There is therefore only one component of this text for which I can claim sole responsibility. The errors in these pages are mine alone, and not the fault of anyone whose collaboration or ideas have helped me conceive this book.

The fieldwork I conducted in Mali and Congo was funded by the Brown University PSTC, the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research (grant no. 7215), and the National Science Foundation (grant no. BCS-0413600).

I thank Dee Mortensen of Indiana University Press for her unfailing dedication to her editorial calling, through revisions and title changes that would have frustrated mere mortals. Her faith in this project helped me see it through to completion. Independent copy editor Rita Bernhard smoothed the rough edges of my prose with astounding thoroughness and skill.

Finally, my deepest appreciation and respect is for Oumou Coulibaly, who has been with me through every stage of this process from inception to fieldwork to publication. Her support has meant the world to me.

INTRODUCTION

EXILE KNOWS NO DIGNITY

In the heart of West Africa's arid Sahel region, on a dusty plain a few hours drive north of the Niger River, lies a community of several thousand inhabitants. I call this community Togotala, although that is not its real name. It is a large villagemore of a small town, reallyset amid fields of rust-colored laterite earth dotted with scrub brush and thorny acacia trees.

Togotala, being in the Sahelian zone, receives almost no rain for nine months of the year, from October until June. What vegetation exists there is gradually consumed by local residents livestock, until by April and May little is left growing at ground level; the only green visible is foliage above the reach of cattle and goats. Even after a good year, the animals grow thin and bony in this period. After a bad year they start dying in droves, endangering their owners livelihoods and raising the specter of crop failure if the seasonal drought lasts too long. Usually between July and September rains finally fall, sometimes in torrents. During a big storm the water sluices through low-lying areas, eroding great gashes into the unpaved streets and occasionally collapsing the mud-brick homes many families build for themselves in this part of Africa. We are threatened when the rain doesn't come, a resident once told me wryly during the rainy season, and we are threatened when the rain comes.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.