First published 2002 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2002 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2001050777

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Oppong, Yaa P.A.

Moving through and passing on : Fulani mobility, survival, and

identity in Ghana / Yaa P.A. Oppong.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-7658-0126-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Fula (African people)Migrations. 2. Fula (African people)

Ethnic identity. 3. Fula (African people)Social conditions. 4. Cattle

herdersGhana. 5. GhanaSocial conditions. I. Title.

DT510.43.F84 O66 2002

306.09667dc21

2001050777

ISBN 13: 978-0-7658-0126-5 (hbk)

For Ma and Pa with love and gratitude

Everybody in Africa [knows] that Fulaniare from one country, but the reason why we divided ourselves isbecause ofour sheperd work When you take your cow you pass here. This man takes his, he pass[es] there, then you get into the bush. You go far away and you just settle somewhere, you just look [after] your cows. You go where you have good grass (Mohammed)

it is because ofour cow. We follow our cow, then we go and we forget our home (Abdulrahmane)

California, Kansas City, Chicagothis area is a farming placeso we always call George Bush [and] ReaganFulani, because they are cowboys. (Abdulrahmane)

A few months into my fieldwork, after an especially long and complicated interview in a remote rural spot, the old man with whom I had been speaking, said to me, And how is your father, Professor Oppong? I was astonished. I had spent more than four hours inquiring about this mans family, completely unaware that from the outset he already knew about me and mine! Thirty years ago, my father, a veterinarian, treated cattle on the Accra Plains and also conducted fieldwork for his own Ph.D. thesis on cattle skin diseases in Greater Accra. This involved working closely with Fulani herds-men, among whom he earned a considerable reputation. The man I interviewed had worked with and known my father.

Now, three decades later, it became apparent to me that the welcome that I received and the trust invested in me by members of the Fulani community were based upon the fact that some people knew my own family and fragments of my life story. There seemed no greater guarantee of assistance than being introduced as Professor Oppongs daughter! (bii

I owe my greatest debt of thanks to my mother, Professor Christine Oppong, for her unconditional support and inspirational example. Thank you, Ma: for your encouragement when the road seemed long; for reminding me of the bigger picture when I lost my way in the mire of details; for patiently reading my countless drafts and for always being there across space and through time!

I also want to thank Amina and Ibrahim, who helped me in untold ways. To the Sido, Yero and Belko families, who took me in as their daughter and sister and to my many Fulani friends and teachers, brothers and sisters, a heartfelt, mi yetti sanne. Thank you for sharing your stories and lives with me, and for patiently responding to my constant questions.

I am grateful to Professor Richard Fardon, my doctoral supervisor, for painstakingly reading and critiquing my emerging manuscript and for his steadfast assistance throughout this long and intellectually enriching process. Thank you also to Professor John Peel and Professor Richard Rathbone of SOAS for their institutional support and encouragement. Thanks also to Dr. Kwaku Yeboah of the Sociology Department, University of Ghana, who provided technical advice and psychological support at a crucial moment in the development of this work.

Some people wanted their names to be known, others wanted to remain anonymous. I have changed the names of people and places in some instances and hope that I have done justice to their wishes.

Notes

. This book started life as my doctoral thesis, We follow our cow and forget our home.Movement, Survival, and Fulani Identity in Greater Accra, Ghana, presented for the degree of doctor of philosophy at SOAS, University of London, in 1999.

. The implosive voiced consonants in Fulfulde are not marked in this text.

. Akan for thank you.

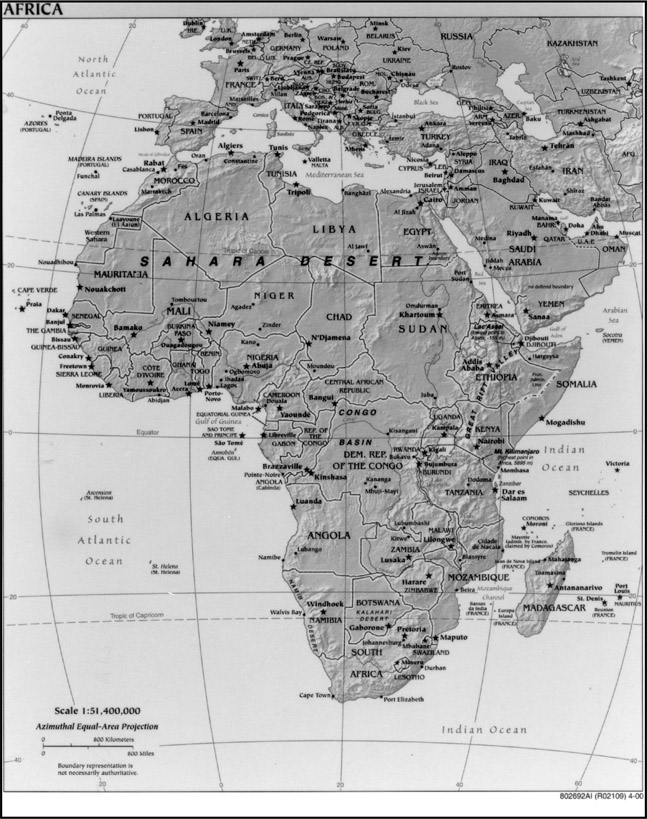

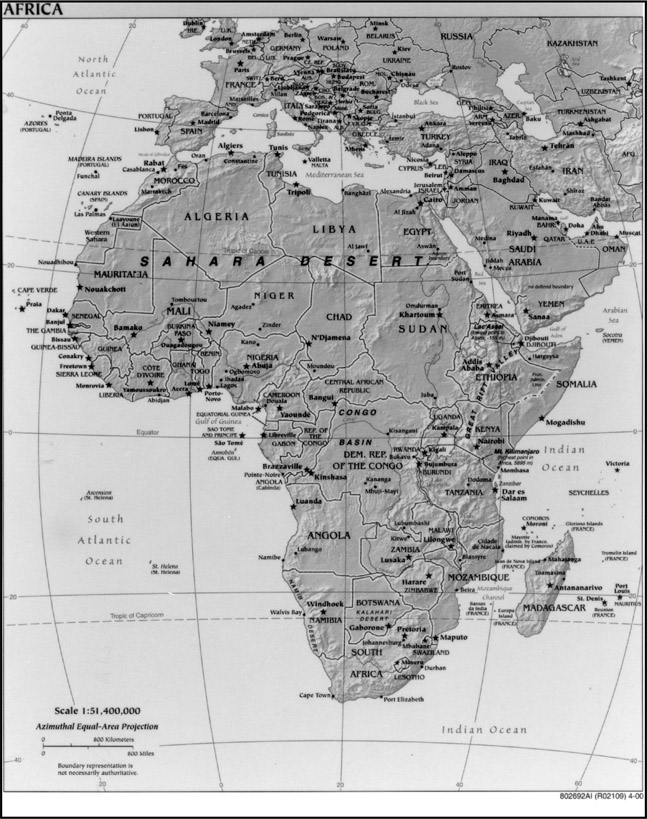

Source: Central Intelligence Agency (2000), Washington, DC.

1

Introduction

This study is concerned with Fulani identities and mobility in Greater Accra, Ghana. It is ultimately concerned with Fulani survival across space and through time. It involves an understanding of where people are coming from, where they have travelled to and the environments in which they have grown up, been educated, married, borne children and worked. The units of analysis are the lives, stories and experiences of individuals, as well as the communities and ultimately ethnic group of which they form a part. The account thus addresses the personal troubles of individual women and men, both young and old, as well as wider public issues taken up by the Ghanaian state and press (Wright Mills 1959: 8). These issues are also observed to be the subject of debate and concern in the Fulani community in Greater Accra.

Many of the questions raised in this book are addressed and graphically illustrated in the following vignettes. The first sketch, of a street parade, is an illustration of the ways in which the politics of Fulani identity is explicitly mobilized at the community level in Greater Accra. The second, the story of Shuhaibu Abdul-Hairu and his journey to Ghana, represents an individuals mobility over time.

A Fulani Street Procession in Accra

In February 1997, the end of the Muslim fasting period of Ramadan was celebrated by the Muslim people of Nima, Accra, with a procession through the main street. This particular organization was established by Ghanaian-born Fulani.

The women in the Fulani procession had their hair intricately plaited and were carrying large calabashes of fresh milk on their heads. The men were dressed as herdsmen. The costumes they were wearing, traditional Nigerian Fulani dress, had been chosen by elder members of the association.

You see, the Mali[an] dress is different. The Burkina ones are also different, Niger also has different traditional dress. This year it was the Nigerian Fulani dress that we chose. Last year we used the Burkina Fulani dress. God willing next year we will choose a different dress, maybe we will choose Cameroon or Mali, or Gambia or other countries. (Mohammed Toure, Chairman of the Great Fulani Association)