PREFACE.

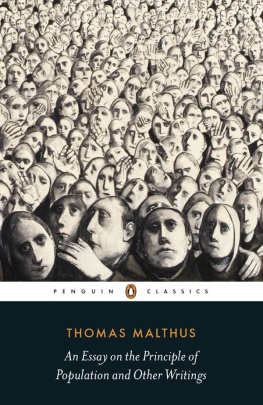

Since 1877, when the Lord Chief Justice of England in his charge to the jury pronounced the discovery of Malthus to be an irrefragable truth, a vast amount of literature has appeared upon the population question. The conclusion come to by many of the most recent writers has been in accord with that pithy expression of John Stuart Mill, where he says: Every one has a right to live. We will suppose this granted. But no one has a right to bring children into life to be supported by other people. Whoever means to stand upon the first of these rights must renounce all pretension to the last. Mr. Cotter Morison, a distinguished writer, says, in his work entitled The Service of Man: The criminality of producing children whom one has no reasonable probability of being able to keep, must in time be seen in its true light, as one of the most unsocial and selfish proceedings of which a man nowadays is capable. If only the devastating torrent of children could be arrested for a few years, it would bring untold relief. Sir William Windeyer, of New South Wales, in a judgment delivered in 1888, concerning a Malthusian work, says: It is idle to preach to the masses the necessity of deferred marriage and of a celibate life during the heyday of passion.... To use and not abuse, to direct and control in its operation any God-given faculty, is the true aim of man, the true object of all morality. The Rev. Mr. Whatham, in a pamphlet entitled Neo-Malthusianism, says: It becomes the duty of every thoughtful man and woman to think out some plan to stop or even check this advancing tide of desolation; and the only plan, to my thinking, that is at all workable is artificial prevention of child-birth. Professor Mantegazza, Senator of Italy, says, in his Elements of Hygiene, to those affected with hereditary diseases: Love, but do not beget children. The Rev. Mr. Haweis says, in Winged Words: Overpopulation is one of the problems of the age. The old blessing of increase and multiply, suitable for a sparsely peopled land, has become the great curse of our crowded centres. Mr. Montague Cookson says: The limitation of the family is as much the duty of married persons as the observance of chastity is the duty of those who remain unmarried. Professor Huxley, the Bishop of Manchester, Mr. Leonard Courtney, Dr. William Ogle, and the Archbishop of Canterbury have all recently endorsed the truth of the Malthusian law of population, which, as Mr. Elley Finch has truly said, is, in company with the Newtonian law of gravitation, the most important discovery ever made.

CHARLES R. DRYSDALE, M.D.

23 Sackville-street, Piccadilly, London, W.

October, 1892.

THE LIFE AND WRITINGS

OF

THOMAS R. MALTHUS.

A great deal has been said in Courts of Law during the last two years about the Malthusian principle of population. The Lord Chief Justice of England has pronounced that it is an irrefragable truth, and that all parties who have studied such questions know, since the days of the Rev. T. R. Malthus, that the great cause of indigence is the tendency that population has to increase faster than agriculture can furnish food. And yet we have serious doubts whether one out of a thousand of the population of the British Islands knows who Mr. Malthus was, or, indeed, whether he was a Roman, or a citizen of modern Europe, at all. It is, therefore, we are convinced, very important to let his countrymen know that Thomas Robert Malthus was an Englishman; that he was a denizen of the 19th century; and that he lived most part of his life in the neighbourhood of London.

Thomas Robert Malthus was born at the Rookery, near Dorking, in Surrey, in 1766. Those who are interested in the matter will do well to make a pilgrimage, as we have done, to the romantic birth-place of the discoverer of the law of population, the greatest (if we measure discoveries by their effect on human happiness) ever made. Malthus father was an able man, a friend and correspondent of the noble and unfortunate J. J. Rousseau, and one of his executors. Thomas Robert was his second son, and, as a boy, evinced so much ability that his father kept him at home and superintended his education himself. The son repaid his fathers care, and had awakened in him that spirit of independence and love of truth which were ever afterwards the characteristics of his mind. He had two tutors, in addition to his father, both men of geniusRichard Graves and Gilbert Wakefieldthe former the author of the Spiritual Quixote, the latter the correspondent of Fox, and well known in his day as a violent democratic writer and politician.

In 1784, when 22 years of age, T. R. Malthus went to Cambridge; and, in 1797, became a Fellow of Jesus College. After this he took orders, and for a time officiated in a small parish near his fathers house, in Surrey. In 1798, appeared his first printed work, which may be seen in the British Museum. It is entitled An Essay on the Principle of Population, as it affects the future Improvement of Society; with Remarks on the Speculations of Mr. Godwin, Mr. Condorcet, and other Writers.

The writer in the Encyclopdia Britannica, from whom these details of Malthus life are taken, informs us that the book was received with some surprise, and excited considerable attention, as being an attempt to overturn the prevalent theory of political optimism, and to refute, upon philosophical principles, the speculations then so much in vogue, as to the indefinite perfectibility of human institutions. In this remarkable essay the general principle of population, which Wallace, Hume, and others had very distinctly enunciated before him, though without foreseeing the consequences that might be deduced from it, was clearly expounded; and some of the important conclusions to which it leads in regard to the probable improvement of human society were likewise stated and explained; but his illustrations were not sufficient, and he, therefore, sought in travel further confirmation of his theories.

In 1799 he visited Norway, Sweden, and Russia, and, after the peace of Amiens, France; in which countries he busily collected all the data he could bearing upon his researches. In 1815 he was appointed to the professorship of political economy and modern history at Haileybury, near London, which chair he occupied until his death in 1834, at the age of 70. He left behind him one son and one daughter. The son is, we believe, still alive, or was so a few years ago.

The account given by Mr. Malthus of the way in which he discovered the law of population is to this effect. His father, Mr. Daniel Malthus, a man of romantic and somewhat sanguine character, had espoused warmly the doctrines of the great writers Condorcet and Godwin, with respect to the perfectibility of man, to which the sound sense of the son was always opposed; and when the subject had been very frequently discussed between them, and the son had always objected to Godwins views, on account of the tendency of population to increase faster than subsistence, he was asked by his father to put down in writing his views on this point. The result was the Essay on Population; and his father was so much struck with the value of the arguments, that he recommended his son to publish it.