The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Lisa See Endowment Fund in Southern California History and Culture.

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2020 by Roco Rosales

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rosales, Roco, 1983 author.

Title: Fruteros : street vending, illegality, and ethnic community in Los Angeles / Roco Rosales.

Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019052050 (print) | LCCN 2019052051 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520319844 (cloth) | ISBN 9780520319851 (paperback) | ISBN 9780520974166 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH : Street vendorsCaliforniaLos Angeles. | Ethnic neighborhoodsCaliforniaLos Angeles. | ImmigrantsCaliforniaLos AngelesSocial conditions. | Hispanic AmericansSocial conditions. | Latin AmericaEmigration and immigration.

Classification: LCC HF 5459. U 6 R 67 2020 (print) | LCC HF 5459. U 6 (ebook) | DDC 381/.180979494dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019052050

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019052051

Manufactured in the United States of America

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

1

Introduction

Jess was the first frutero I visited regularly and befriended. They work behind large pushcarts weighed down by many pounds of produce and ice under rainbow-colored umbrellas (see figure 2). On their street corners, fruteros prepare and sell made-to-order fruit salads.

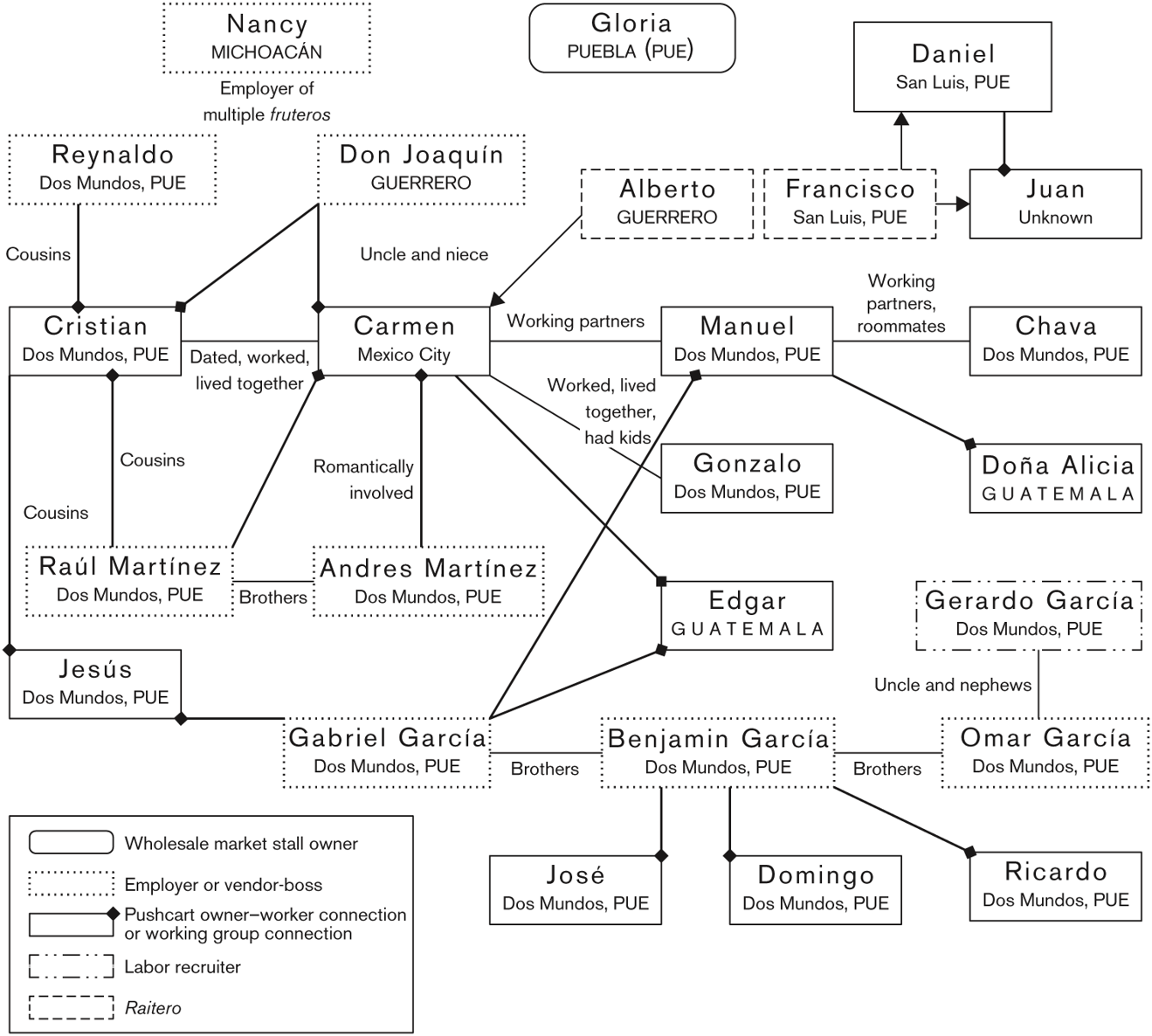

Figure 1 . Fruit vendor paisano network.

Figure 2 . A frutero working in central Los Angeles.

Jess was clearly perplexed at my presence in the beginning; I asked too many questions, and I stood too close to him because his infrequent and soft-spoken responses were barely audible above the constant din of street traffic. At five feet six, he was two inches taller than me, but he never stood straight, so we were mostly at eye level. He was twenty-one years old when I met him in 2006. He was slender and dark skinned with a wispy mustache and goatee. His standard uniform included dark wash, loose-fitting jeans with arabesque tan stitching over the back pockets and an equally loose-fitting black hoodie. Jess never looked directly at me. He always kept his eyes directed down at the waist-level tray table where he prepared fruit. Oftentimes while talking, he would wipe a wet rag across the cutting board and tray table to busy his hands and give his downward gaze a purpose. Jess sold made-to-order fruit salads on Pico Boulevard.

Pico Boulevard runs from downtown Los Angeles all the way to the coastal city of Santa Monica. Standing along it, one is visible to thousands of passing motorists and pedestrians. Fruit vendors work out of large and heavy pushcarts; through the Plexiglas tops of these pushcarts, customers can see and pick which fruits and vegetables they want to include in their prepared-on-site fruit salads. Service is always quick: less than three minutes after making a selection, customers have a clear plastic bag or cylindrical plastic container of chopped fruits and vegetables in hand, garnished with salt and chili powder, with a plastic fork sticking out and inviting the customer to dig in.

One day, after two weeks of almost daily visits, I was late leaving campus and arrived at the vending site after the 3 p.m. school pickup rush. When I approached, I saw that his pushcart was nearly empty. I almost thought you werent coming today, he told me. I dont have any good fruit left. papaya, and on this occasion, oranges. I agreed. I came for the conversation, not for the fruit.

Do you work every day? I asked.

I keep bank hours, he replied and then laughed at my puzzled face. With his knife he gestured toward the bank he was standing in front of and said that he worked six days a week, with reduced hours on Saturdays, and was closed on Sundays.

Are the bank customers your customers?

Some of them. I can give them smaller bills after they visit the [ATM] machine. But I get school kids and people who ride the bus and people going to work. With his chin he motioned to a passing bus behind me. A westbound bus making local stops brought a steady stream of people every twenty to thirty minutes during off-peak hours. I rode the bus to get to Jesss corner as well. The Big Blue Bus, a bus system based out of the city of Santa Monica, would leave me half a block past the bank where he worked, so I often saw him through the large bus windows tending to customers as I arrived.

Throughout the following weeks, I varied my arrival times to get a sense of Jesss workday. Some days, I arrived late and helped him put things away; other days I arrived early and watched him set up. The days were routine and mundane, and when Jess did not have customers, he texted friends and family on his phone. He talked about getting bored often and explained that he was trying to learn how to nap while standing up. Figuring out successful leans to achieve this became part of an ongoing conversation.

It took many visits before I felt comfortable talking about issues related to immigration status. The topic eventually came up when Jess asked me, Do you have legal status papers? I explained that I was born in Texas to Mexican immigrant parents. Jess was from a small, rural town in the Mexican state of Puebla and had arrived in the United States only a few months before I met him. Though he had entered into the country without authorization, he knew he had a job waiting for him as a fruit vendor. A former neighbor in Puebla who now lived in Los Angeles had promised him the job. Jess had a wife and two young children in Puebla. He intended on returning to them just as soon as he made enough money to pay for his wifes medical bills. During each of my visits, I would learn something new and interesting about Jess and his job.

One midweek day after a couple of months of visits, the bus I was riding passed the bank, but there was no sign of Jess. I thought I might stay aboard to visit other vendors further along the boulevard but decided to walk to his corner and ask the parking lot attendant if he knew anything about Jesss absence. Along the curb next to the sidewalk where Jess usually parked his pushcart, I saw a melting pile of crushed ice.

Had I just missed him? Why would he leave so early in the day? It was the Salvadoran parking lot attendant who answered all of my pressing questions. The health department had done a sweep. They had dumped Jesss produce into large trash bags and, before taking the pushcart, had asked him to dump out all of the remaining ice onto the sidewalk.

![switching.social [switching.social] - The Switching Social Handbook](/uploads/posts/book/131346/thumbs/switching-social-switching-social-the-switching.jpg)