First published 2007 by Paradigm Publishers

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2007, Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Martnez, Samuel, 1959-

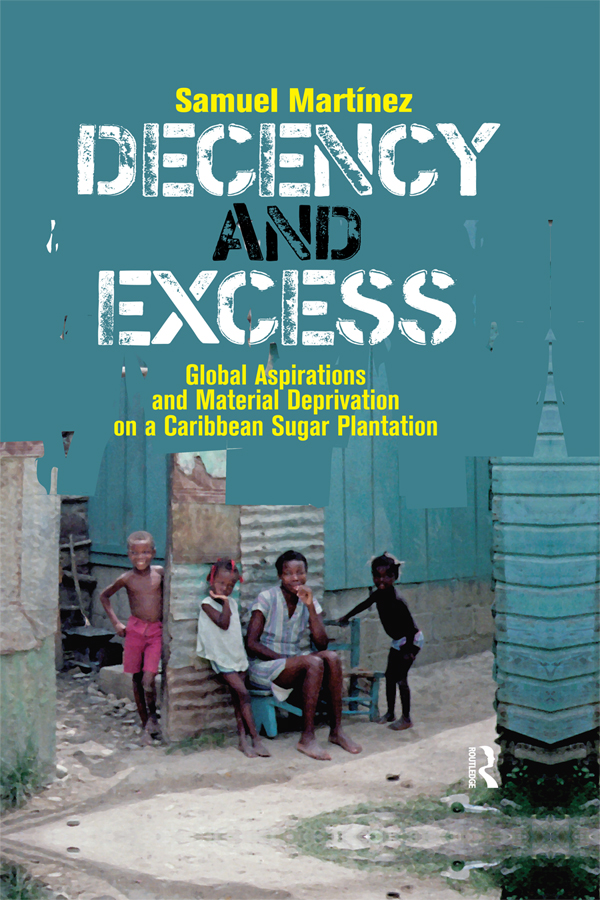

Decency and excess: global aspirations and material deprivation on a Caribbean

sugar plantation / Samuel Martnez.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59451-187-5 (alk. paper)

1. Sugar workersDominican RepublicBatey Monte CocaSocial

conditions. 2. Sugar workersDominican RepublicBatey Monte Coca

Economic conditions. 3. Commercial productsSocial aspectsDominican

RepublicBatey Monte Coca. 4. Alien labor, HaitianDominican Republic

Batey Monte Coca. 5. Batey Monte Coca (Dominican Republic)Ethnic

relations. I. Title.

HD8039.S86D645 2007

331.76336109729381dc22

2006035189

ISBN 13: 978-1-59451-187-5 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-59451-188-2 (pbk)

Designed and Typeset by Straight Creek Bookmakers.

This book may well be one of holistic ethnographys last hurrahs. Much of todays cultural anthropology inhabits archives, global networks, even cyberspace, examines texts or popular media, or, in a quite different vein, is guided by reductive bio-evolutionary theories and esoteric statistical methodologies. There is reason to celebrate if cultural anthropology has broadened its concerns and expanded its concepts regarding what counts as knowledge. Yet if, as a result of these trends, we lose touch with the kinds of peoplepushed out of sight and hearing by the corporate mediawhom our discipline has in the past excelled in bringing into view, then I think anthropologys current trends also give reason for regret. Today, neither the scientific nor the post-modernist wing of cultural anthropology places much trust in participant-observation-based, holistic fieldwork: the first camp dismisses it as too subjective; the second distrusts it for being implicated with Western global domination and wedded to realist narrative conventions. I believe that broad-ranging, community-based, empirical field study is not only still viable but should be assuming expanded importance in the present era of economic globalization. Only through this approach can cultural anthropology raise awareness of globalizations geographically and socially uneven outcomes and contribute to scholarly understandings of how local actors respond, when caught on the scissors of declining industrial production paired with rising consumer aspirations. Only by going to economically depressed communitieswhether these be located in the under-developed or the excessively developed economies of the worldand talking to the people who live there, can we appreciate the human costs of todays accelerated capital restructuring. At the present global historical conjuncture, it would be ironic if cultural anthropology were to turn its back on the painstaking study of matters particular to localities around the globe. When critics and theorists join voices in raising concerns about the destructive effects of global economic forces and trends on local traditions and economic initiatives worldwide, should we not revitalize our fieldwork tradition sooner than abandon it?

While we should not give up on holistic ethnography, neither should we be uncritical of cultural anthropologys guiding concepts. I see particular need for greater critical scrutiny of anthropologists all-too-frequent tendency to attribute all and sundry aspects of belief and behavior to culture. Anthropologists have conventionally reified and totalized culturenot just studying it but seeing it as a thing, active in the world, and the primary cause of the social phenomena we observe. These ways of thinking about culture live on in our thinking and inevitably lead ethnographers into the interpretive trap of implicitly either idealizing or vilifying others ways of life. Whether it bears a positive valence, signifying that a groups way of life is deserving of toleration, or a negative charge, implying that the group carries a social pathology (e.g., the culture of abuse at Abu Ghraib), culture is never politically neutral. Judgment, I fear, is built into the culture concept. Even eschewing the attribution of causality to culture, it may be that judgment is hard to avoid. I may unconsciously fall into it in other ways. Yet I think the people whose ways of life I have studied would not be well served by the positive or negative judgment inevitably connoted by characterizing all their beliefs and behavior as a product of culture.

Truth be told, were the way of life that I describe in this book to disappear tomorrow, no one, not even I, would much regret its passing. There is little that is whole, satisfying, and authentic, and not much very particular, great or of irreplaceable value, about this communitys life ways. Monte Cocathe company compound for agricultural workers ( batey ) where I have done my fieldwork on a sugar plantation in the Dominican Republicwas enveloped by the rising tide of primary commodity export development that Europeans and North American business enterprises brought to much of the tropics in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. The settlement was created in the process of converting the land around it into a massive for-profit agricultural industrial complex, and thus stripped clean of its place-specific cultural attributes. Amid the detritus of Western commodity culture, things unique, integral, genuine and enduring are hard to find. The existence in Monte Coca and other bateyes of a distinct system of spiritual belief and ritual, for example, centering on service to the gods of Haitian vodou, may be regarded as all the more precious for having been pieced together by settlers and sojourners from elsewhere. In past years, cultural anthropologists would look only at such genuinely particular aspects of culture, and turn their gaze away from the surrounding shops, bars, store-bought adornments, and work for wages; many an ethnographer would still. Yet, inauthentic, faddish and familiar though these circumstances of life might accurately be described to be, I am convinced it would diminish our understanding of peoples lives in Monte Coca to focus primarily on things authentic, particular and enduring. Both things, the culturally authentic and the inauthentic, are means by which batey residents desire beyond adequacy, seek to transcend the limitations of the everyday, and in so doing tacitly affirm their humanity.