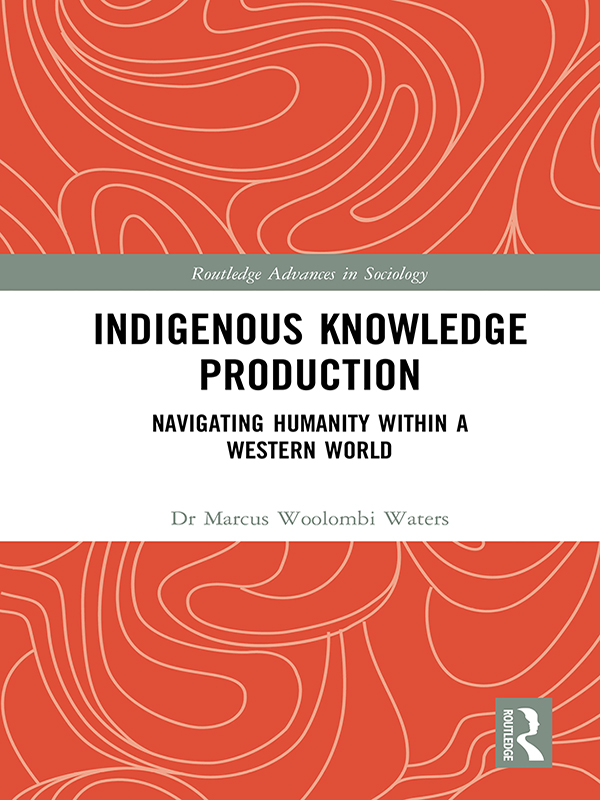

Indigenous Knowledge Production

Despite many scholars noting the interdisciplinary approach of Aboriginal knowledge production as a methodology within a broad range of subjects including quantum mathematics, biodiversity, sociology and the humanities the academic study of Indigenous knowledge and people is struggling to become interdisciplinary in its approach and move beyond its current label of Indigenous Studies.

Indigenous Knowledge Production specifically demonstrates the use of autobiographical ethnicity as a methodological approach, where the writer draws on lived experience and ethnic background towards creative and academic writing. Indeed, in this insightful volume, Marcus Woolombi Waters investigates the historical connection and continuity that have led to the present state of hostility witnessed in race relations around the world, seeking to further understanding of the motives and methods that have led to a rise in white supremacy associated with ultra-conservatism.

Above all, Indigenous Knowledge Production aims to deconstruct the culturallens applied within the West which denies the true reflection of Aboriginal and Black consciousness, and leads to the open hostility witnessed across the world. This monograph will appeal to undergraduate and postgraduate students, as well as postdoctoral researchers, interested in fields such as Sociology of Knowledge, Anthropology, Cultural Studies, Ethnography and Methodology.

Dr Marcus Woolombi Waters is a Lecturer in the School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science at Griffith University, Australia.

Routledge Advances in Sociology

For a full list of titles in this series, please visit www.routledge.com/series/SE0511

Reflections on Knowledge, Learning and Social Movements

Historys Schools

Edited by Aziz Choudry and Salim Vally

Social Generativity

A relational paradigm for social change

Edited by Mauro Magatti

The Live Art of Sociology

Cath Lambert

Video Games as Culture

Considering the Role and Importance of Video Games in Contemporary Society

Daniel Muriel and Garry Crawford

The Sociology of Central Asian Youth

Choice, Constraint, Risk

Mohd. Aslam Bhat

Indigenous Knowledge Production

Navigating Humanity within a Western World

Dr Marcus Woolombi Waters

Time and Temporality in Transitional and Post-Conflict Societies

Edited by Natascha Mueller-Hirth and Sandra Rios Oyola

Practicing Art/Science

Experiments in an Emerging Field

Edited by Philippe Sormani, Guelfo Carbone and Priska Gisler

The Dark Side of Podemos?

Carl Schmitt and Contemporary Progressive Populism

Josh Booth and Patrick Baert

Indigenous Knowledge Production

Navigating Humanity within a Western World

Dr Marcus Woolombi Waters

First published 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2018 Marcus Woolombi Waters

The right of Marcus Woolombi Waters to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book has been requested.

ISBN: 9781138218383 (hbk)

ISBN: 9781315437811 (ebk)

Biiba-ga guwaa-lda-ndaay

(A note from the author )

What does it mean to be Aboriginal in the 21st century? To be connected to the land beyond materialism and commodity, where instead your connection is within the kinship ties, and the very DNA you possess that comes from the land you walk on. Surely in connecting to the land our very humanity is then connected to our Aboriginality. As the oldest living culture practised today our Aboriginality is our divine authority and birthright to exercise autonomy, ownership and leadership as the original peoples of these lands in which we remain connected to today. To claim ownership in our wellbeing free of trauma as a people belonging to the lands of their ancestors over tens of thousands of years we share a noble birth in carrying the legacy of our languages, our ceremony and our way of life into the future. As a Kamilaroi Australian Aboriginal I live in one of the richest Western countries in the world, built on an industry of mining from the lands of my own Aboriginal people, many of whom remain living in third-world poverty and associated trauma.

This is poverty and trauma I have seen and felt personally. Just over 12 months ago I took a one-year sabbatical to write this book. I left Australia for New Zealand to be picked up by my white sister, who is also my aunt, having been adopted by my white grandparents after being taken from my Aboriginal mother 48 years ago. My narrative is unique in that rather than writing about my being taken or returning to my Aboriginal family, a text many are familiar with due to publications already documenting Australias Stolen Generations including Follow the Rabbit-proof Fence (Pilkington, 2013) and My Place (Morgan & Reynolds, 1987), I am now returning to the white family that reared me. Hopefully in coming full circle within my own healing process. My first emotional trigger is in giving into the white privilege I walked away from as a teenager in being reunited with my Aboriginal family over 30 years earlier.

My sister lives in a million-dollar house in Wellington, the nations capital. To my Aboriginal family, owning a million-dollar house is as far removed from reality as travelling to the moon. As Aboriginal people we just dont own million-dollar houses, but for many white Westerners living in major cities around the world, including Wellington, Auckland, Sydney or Melbourne, this is neither extraordinary nor extreme in fact, it is normal. You just cant get standard four-bedroom housing in these inner cities for anything living in inner Sydney or Melbourne, as a form of socioeconomic cultural apartheid (Wright, 2002). I stay with my sister for two days as, together with my two boys, Ngiyaani (13 years old) and Marcus junior (12 years old), we get reacquainted. I purchase a car from a car-yard owned by a friend of her husband, well under market value; because of the relationship with family the car has been checked out and is running A1 mechanically. I pay cash, which is expected, and leave for Hastings, which is a four-hour drive away, with peace of mind and security knowing the car wont break down or be in need of constant maintenance, even though I paid less than A$2,000. It is hard describing such purchases as white privilege, or even as a benefit to those who see such social and cultural capital as matter-of-fact or as personal agency they believe acquired from hard work, but I have lived with poverty associated with my Aboriginality and these are not securities associated to everyone where even a safe, reliable car appears out of reach. I arrive in Hastings and take up residence in a house owned again by a friend of the family, and together with my two boys and my white family we start a process of what I hope will be healing.