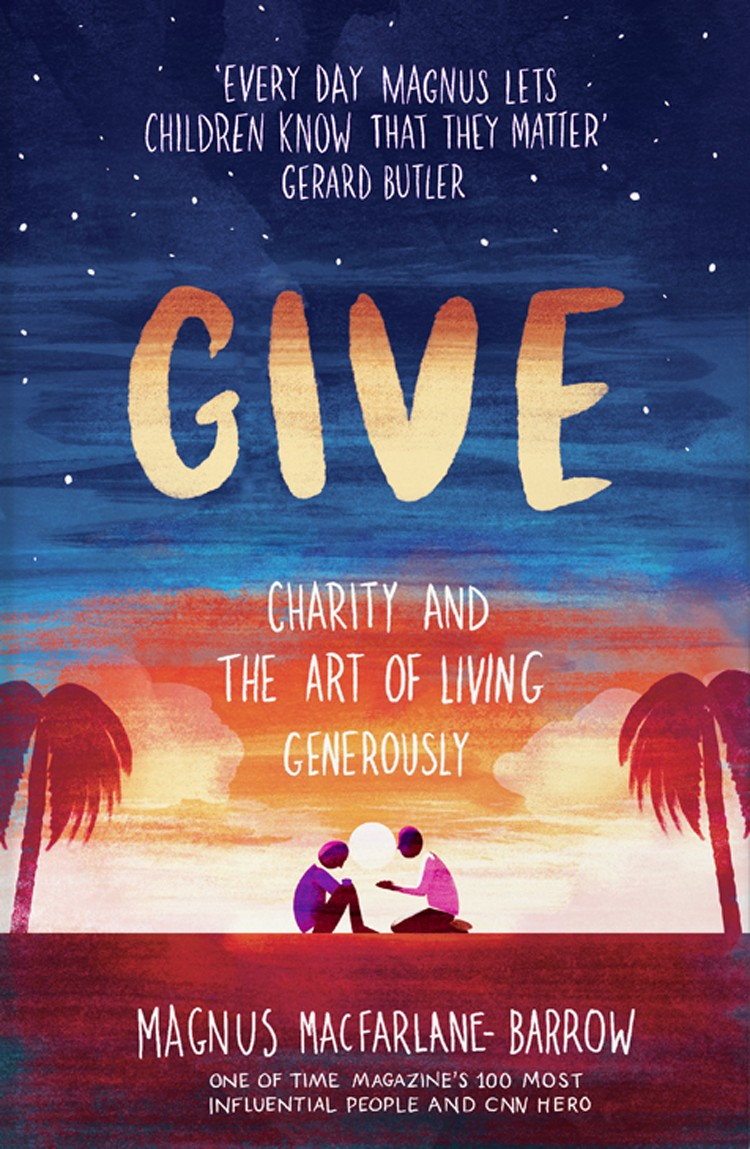

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2020

Copyright Magnus MacFarlane-Barrow 2020

Scripture quotations marked ESV are from the ESV Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version), copyright 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations marked NJB are taken from The New Jerusalem Bible, published and copyright 1985 by Darton, Longman & Todd Ltd and Doubleday & Co., Inc., a division of Random House, Inc. and used by permission.

Magnus MacFarlane-Barrow asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008360016

eBook Edition September 2020 ISBN: 9780008360023

Version: 2020-05-27

Charity to me will always smell of freshly baked bread. During the summer of 1985, even as the man on the radio updated us on the Ethiopian famine and its mounting death toll, my mother was pulling yet another batch of loaves from our oven. She was supporting a local fundraising effort aimed at helping those facing imminent starvation. Each warm loaf was adding to the delicious aroma in our house, before being delivered to the village hall to be sold amid an assortment of donated home baking.

Beyond our village, across the whole country, a plethora of such fundraising events were taking place that summer, the world having been stirred into action by an extraordinary news report by BBC reporter Michael Buerk. From a refugee camp in Tigray, surrounded by the dead and dying, he had described to us the closest thing to hell on earth. Among the many fundraising efforts born in response to that horror, one dwarfed all others in its scale and ambition.

On 13 July 1985, along with 30 per cent of my fellow human beings, I sat down to watch Live Aid on the television. For a teenager living in the pre-internet era, the opportunity to spend a whole day with my friends enjoying live performances by the superstars of rock and pop felt almost too good to be true.

It was a great day. We cheered the bands we were fans of and ridiculed the ones we didnt appreciate although once or twice we had to begrudgingly admire even some of their performances. As the bands in Wembley played on into the evening, the US version began in Philadelphia and some live performances from there were also beamed back to us. No one said as much, as we joked and laughed and debated each artists performance, but it felt as if we were part of something special. By now Bob Geldof was giving us regular reminders of what this spectacular event was all about raising funds to help the 8 million people who faced starvation in Ethiopia. At one point in the evening, David Bowie, having belted out We Can Be Heroes, Just for One Day, introduced a short video. It was four minutes of the most harrowing images I had ever seen. Suddenly in the room with us were emaciated children with protruding ribs and bloated stomachs, the piercing scream of a child, a tiny bandaged corpse. It was deeply shocking. We took turns using the house phone to call and pledge our own donations. I think it might have been the first gift to charity I ever chose to make. (I had long been putting coins in the plate at Sunday Mass but that didnt feel very optional.) As I hung up the phone, having shared my bank card details and a very little of my summer job earnings, I was surprised by a fleeting, unfamiliar feeling; a stab of joy and a momentary yearning to be someone better and for the world to be something better too. I dont think it was just the beer.

Aside from the trauma of watching Scotland play football in the World Cup, Live Aid is the only vivid recollection I have of watching something on television in my youth. I am not sure if the experience played any part in my later journey into overseas aid work there were certainly other, more obvious, triggers that led me to that but I do believe that event in the summer of 1985 had an influence on the way I, and others of my generation, feel about certain things. The advances in technology that enabled us to watch those simultaneous concerts and which brought us distressingly close to the suffering in Ethiopia were creating new neighbours in distant countries; both those who urgently needed our help and those with whom we could respond in solidarity. Live Aid not only made charity feel possible, it made it feel cool, to use a word of the time. Having grown up in a devout Christian family, I had a fairly well-developed understanding of, and belief in, our duty to help the poor. From earliest memory long before our house became a bakery that summer I had been witnessing acts of charity. Some, like the making of bread, were quite mundane while others, such as my parents unlikely decision to foster a seven-year-old boy with serious health issues, were more radical. I was familiar too with the stories of saints of old and their heroic acts of charity, but even so, the message just felt a bit different when delivered by Neil Young or Elvis Costello and received in the company of my best friends. For better or worse, without us knowing it, the era of celebrity-led charity campaigning had just been born.

Seven years after enjoying Live Aid, my brother and I watched another harrowing report on the television, this time about refugees whose lives had been devastated by the war that was tearing apart the former Yugoslavia. Our response on this occasion was very different. We made a little appeal to friends and family for donations of basic supplies and, having been given them in astonishing quantities, we took one weeks holiday from our jobs (we were salmon farmers) to drive the gifts from Scotland to a refugee camp near Medjugorje in BosniaHerzegovina. I had no notion then that this would lead to the founding of a new charity which would eventually become Marys Meals a global movement which, today, sets up community-owned school feeding programmes in the worlds poorest nations, providing over 1.6 million children with a daily meal in a place of education.

Like the founders of Live Aid, I had no relevant qualifications to lead this work, having simply been moved to act (in a much less ambitious way) by compassion for the suffering people brought close to me by the media. Nor did I have any long-term plan. The journey I set out on twenty-eight years ago has become my lifes work only because that initial outpouring of kindness to our first appeal has never let up. That first trickle of donations has grown into a mighty river fed by little acts of love performed by hundreds of thousands of people all over the world in support of our mission. In Malawi alone, where over 30 per cent of the primary school population eat Marys Meals each day, over 85,000 impoverished volunteers freely offer their time to cook and serve the hungry children of their communities. Meanwhile, in many wealthier countries, a vast army of volunteers, young and old, organise fundraising events, give public talks and take part in sponsored activities in order to provide the funds required to buy the ingredients for each meal. Each day we receive donations of all sizes made by those willing to share what they have so that others might at least eat. Children in primary schools collect coins and sell homemade baking, while their parents might commit monthly donations from their bank accounts. And while most of our support consists of these humble, unheralded deeds of charity, sometimes gifts of spectacular size, or representing radical life choices, are also presented amid this assortment of startling goodness. And each year as the number and value of these gifts grow, so does the number of children being fed.