About the Translator Philip J. Ivanhoe is Reader-Professor in the Department of Public and Social Administration and a member of the Governance in Asia Research Centre (GARC), City University of Hong Kong. His works published by Hackett include Readings from the Lu-Wang School of Neo-Confucianism (edited); Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy (edited, with Bryan W. Van Norden); Confucian Moral Self Cultivation; Ethics in the Confucian Tradition; Virtue, Nature and Moral Agency in the Xunzi (edited, with T.C. Kline III); and The Daodejing of Laozi (translated). His work, with Karen L.

Carr, The Sense of Antirationalism: The Religious Thought of Zhuangzi and Kierkegaard was published by Createspace and is available via Amazon.com.  TRANSLATIONS Chan, Alan K.L. 1991. Two Visions of the Way. Albany: SUNY Press. 1963. The Way of Lao Tzu (Tao te ching). The Way of Lao Tzu (Tao te ching).

TRANSLATIONS Chan, Alan K.L. 1991. Two Visions of the Way. Albany: SUNY Press. 1963. The Way of Lao Tzu (Tao te ching). The Way of Lao Tzu (Tao te ching).

Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (A thoughtful and scholarly translation that makes revealing use of the commentarial tradition.) Henricks, Robert G. 1989. Lao-Tzu Te-Tao Ching. New York: Ballantine. 1990. Tao Te Ching. Tao Te Ching.

New York: Bantam Books. (An elegant and thoughtful translation and study of the Mawangdui version of the text.) Lau, D.C. 1963. Tao Te Ching. Baltimore: Penguin Books. 1999. The Classic of the Way and Virtue: A New Translation of the Tao-Te Ching of Laozi as Interpreted by Wang Bi. The Classic of the Way and Virtue: A New Translation of the Tao-Te Ching of Laozi as Interpreted by Wang Bi.

New York: Columbia University Press. (A masterful translation of the text and Wang Bis commentary. Includes a thorough and insightful study of Wang Bis life and thought.) Waley, Arthur. 1963. The Way and Its Power. (A thoughtful translation with a substantial and impressive introduction.) SECONDARY WORKS Creel, Herrlee G. 1970. What Is Taoism? And Other Studies in Chinese Cultural History. What Is Taoism? And Other Studies in Chinese Cultural History.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Contains several seminal essays on the thought and history of the text.) Csikszentmihalyi, Mark, and Philip J. Ivanhoe, eds. 1999. Essays on Religious and Philosophical Aspects of the Laozi. (An anthology of essays on the thought of the text.) Kohn, Livia, and Michael LaFargue, eds. 1998. Lao-tzu and the Tao-te-ching Albany: SUNY Press. (A broad range of essays on the text, its reception, and interpretation.) Lau, D.C. 1958. 1958.

The Treatment of Opposites in Lao Tzu  , Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 21, pp. 34460. (An intriguing exploration of one of the more paradoxical aspects of the text.) GENERAL STUDIES OF CHINESE THOUGHT Chan, Wing-tsit. 1963. A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 21, pp. 34460. (An intriguing exploration of one of the more paradoxical aspects of the text.) GENERAL STUDIES OF CHINESE THOUGHT Chan, Wing-tsit. 1963. A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fung, Yu-lan. 195253. A History of Chinese Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Graham, Angus C. Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China. Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China.

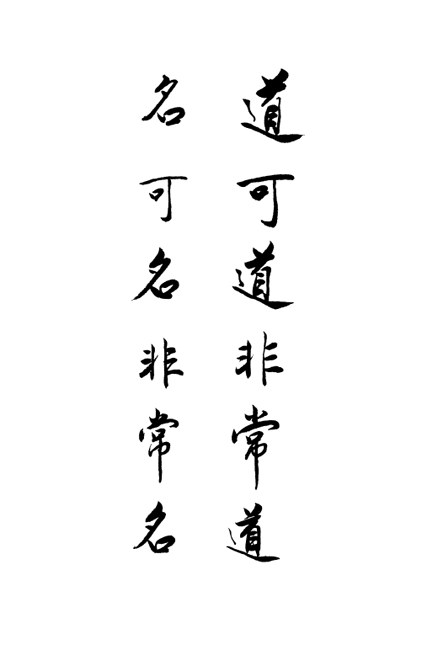

La Salle, Ill.: Open Court. Schwartz, Benjamin I. 1985. The World of Thought in Ancient China. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press.  Chapter One A Way that can be followed is not a constant Way.

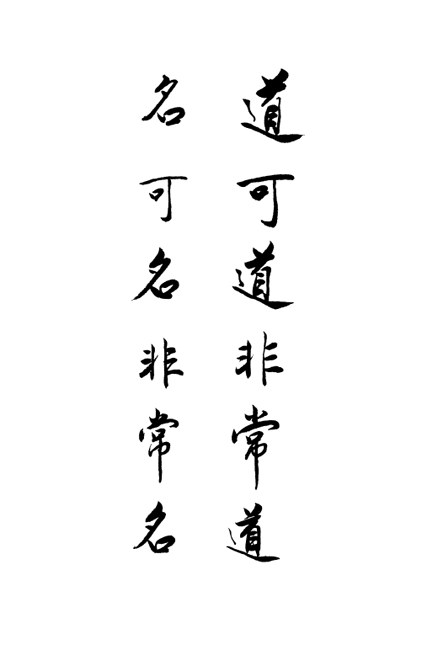

Chapter One A Way that can be followed is not a constant Way.

A name that can be named is not a constant name. Nameless, it is the beginning of Heaven and Earth; Named, it is the mother of the myriad creatures. And so, Always eliminate desires in order to observe its mysteries; Always have desires in order to observe its manifestations. These two come forth in unity but diverge in name. Their unity is known as an enigma. Within this enigma is yet a deeper enigma.

The gate of all mysteries! Chapter Two Everyone in the world knows that when the beautiful strives to be beautiful, it is repulsive. Everyone knows that when the good strives to be good, it is no good.

And so, To have and to lack generate each other. Difficult and easy give form to each other. Long and short off-set each other. High and low incline into each other. Note and rhythm harmonize with each other.

Before and after follow each other. This is why sages abide in the business of nonaction,

and practice the teaching that is without words. They work with the myriad creatures and turn none away. They produce without possessing. They act with no expectation of reward. When their work is done, they do not linger.

And, by not lingering, merit never deserts them. Chapter Three Not paying honor to the worthy leads the people to avoid contention. Not showing reverence for precious goods leads them to not steal. Not making a display of what is desirable leads their hearts away from chaos. This is why sages bring things to order by opening peoples hearts

and filling their bellies. They weaken the peoples commitments and strengthen their bones; They make sure that the people are without knowledge or desires; And that those with knowledge do not dare to act.

Sages enact nonaction and everything becomes well ordered. Chapter Four The Way is like an empty vessel; No use could ever fill it up. Vast and deep! It seems to be the ancestor of the myriad creatures. It blunts their sharpness; Untangles their tangles; Softens their glare; Merges with their dust. Deep and clear! It seems to be there. I do not know whose child it is; It is the image of what was before the Supreme Spirit himself! Chapter Five Heaven and Earth are not benevolent; They treat the myriad creatures as straw dogs.

Sages are not benevolent; They treat the people as straw dogs. Is not the space between Heaven and Earth like a bellows? Empty yet inexhaustible! Work it and more will come forth. An excess of speech will lead to exhaustion, It is better to hold on to the mean. Chapter Six The spirit of the valley never dies; She is called the Enigmatic Female. The portal of the Enigmatic Female; Is called the root of Heaven and Earth. An unbroken, gossamer thread; It seems to be there.

But use will not unsettle it. Chapter Seven Heaven is long lasting; Earth endures. Heaven is able to be long lasting and Earth is able to endure,

because they do not live for themselves. And so, they are able to be long lasting and to endure. This is why sages put themselves last and yet come first; Treat themselves as unimportant and yet are preserved. Is it not because they have no thought of themselves, that they are able to perfect themselves? Chapter Eight The highest good is like water.

Water is good at benefiting the myriad creatures, while not contending with them. It resides in places that people find repellent, and so comes close to the Way. In a residence, the good lies in location. In hearts, the good lies in depth. In interactions with others, the good lies in benevolence. In words, the good lies in trustworthiness.

In government, the good lies in orderliness. In carrying out ones business, the good lies in ability. In actions, the good lies in timeliness. Only by avoiding contention can one avoid blame. Chapter Nine To hold the vessel upright in order to fill it is not as good as to stop in time. If you make your blade too keen it will not hold its edge.

When gold and jade fill the hall none can hold on to them. To be haughty when wealth and honor come your way is to bring disaster upon yourself. To withdraw when the work is done is the Way of Heaven.

Next page

TRANSLATIONS Chan, Alan K.L. 1991. Two Visions of the Way. Albany: SUNY Press. 1963. The Way of Lao Tzu (Tao te ching). The Way of Lao Tzu (Tao te ching).

TRANSLATIONS Chan, Alan K.L. 1991. Two Visions of the Way. Albany: SUNY Press. 1963. The Way of Lao Tzu (Tao te ching). The Way of Lao Tzu (Tao te ching). , Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 21, pp. 34460. (An intriguing exploration of one of the more paradoxical aspects of the text.) GENERAL STUDIES OF CHINESE THOUGHT Chan, Wing-tsit. 1963. A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 21, pp. 34460. (An intriguing exploration of one of the more paradoxical aspects of the text.) GENERAL STUDIES OF CHINESE THOUGHT Chan, Wing-tsit. 1963. A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Chapter One A Way that can be followed is not a constant Way.

Chapter One A Way that can be followed is not a constant Way.