Copyright 2012 by Chris Anderson

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Business, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN BUSINESS is a trademark and CROWN and the Rising Sun colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Anderson, Chris.

Makers : the new industrial revolution / Chris Anderson.

p. cm.

1. Entrepreneurship. 2. Microfabrication. 3. Micromachining. 4. Business enterprisesTechnological innovations. I. Title.

HB615.A683 2013

338.04dc23 2012014398

eISBN: 978-0-307-72097-9

Jacket creative direction and design by Brandon Kavulla

v3.1

For Carlotta Anderson

Contents

Chapter 1

The Invention Revolution

Fred Hauser , my maternal grandfather, emigrated to Los Angeles from Bern, Switzerland, in 1926. He was trained as a machinist, and perhaps inevitably for Swiss mechanical types, there was a bit of the watchmaker in him, too. Fortunately, at that time the young Hollywood was something of a clockwork industry, too, with its mechanical cameras, projection systems, and the new technology of magnetic audio strips. Hauser got a job at MGM Studios working on recording technology, got married, had a daughter (my mom), and settled in a Mediterranean bungalow on a side street in Westwood where every house had a lush front lawn and a garage in the back.

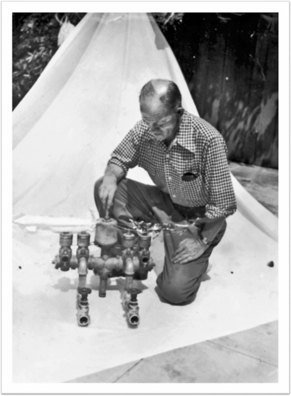

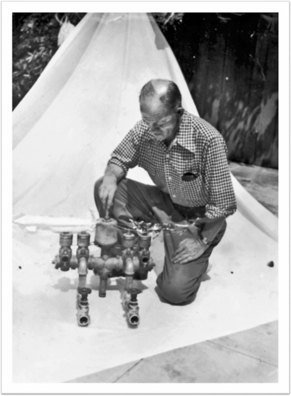

But Hauser was more than a company engineer. By night, he was also an inventor. He dreamed of machines, drew sketches and then mechanical drawings of them, and built prototypes. He converted his garage to a workshop, and gradually equipped it with the tools of creation: a drill press, a band saw, a jig saw, grinders, and, most important, a full-size metal lathe, which is a miraculous device that can, in the hands of an expert operator, turn blocks of steel or aluminum into precision-machined mechanical sculpture ranging from camshafts to valves.

Initially his inventions were inspired by his day job, and involved various kinds of tape-transport mechanisms. But over time his attention shifted to the front lawn. The hot California sun and the local mania for perfect green-grass plots had led to a booming industry in sprinkler systems, and as the region grew prosperous, gardens were torn up to lay irrigation systems. Proud homeowners came home from work, turned on the valves, and admired the water-powered wizardry of pop-up rotors, variable-stream nozzles, and impact sprinkler heads spreading water beautifully around their plots. Impressive, aside from the fact that they all required manual intervention, if nothing more than just to turn on the valves in the first place. What if they could be driven by some kind of clockwork, too?

Patent number 2311108 for Sequential Operation of Service Valves, filed in 1943, was Hausers answer. The patent was for an automatic sprinkler system, which was basically an electric clock that turned water valves on and off. The clever part, which you can still find echoes of today in lamp timers and thermostats, is the method of programming: the clock face is perforated with rings of holes along the rim at each five-minute mark. A pin placed in any hole triggers an electrical actuator called a solenoid, which toggles a water valve on or off to control that part of the sprinkler system. Each ring represented a different branch of the irrigation network. Together they could manage an entire yardfront, back, patio, and driveway areas.

Once he had constructed the prototype and tested it in his own garden, Hauser filed his patent. With the patent application pending, he sought to bring it to market. And there was where the limits of the twentieth-century industrial model were revealed.

It used to be hard to change the world with an idea alone. You can invent a better mousetrap, but if you cant make it in the millions, the world wont beat a path to your door. As Marx observed, power belongs to those who control the means of production. My grandfather could invent the automatic sprinkler system in his workshop, but he couldnt build a factory there. To get to market, he had to interest a manufacturer in licensing his invention. And that is not only hard, but requires the inventor to lose control of his or her invention. The owners of the means of production get to decide what is produced.

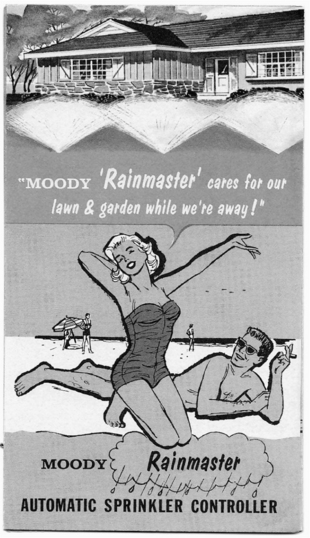

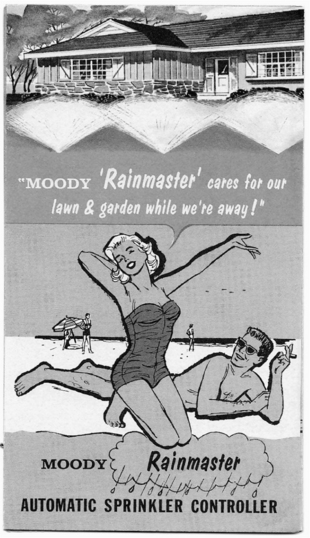

In the end, my grandfather got luckyto a point. Southern California was the center of the new home irrigation industry, and after much pitching, a company called Moody agreed to license his automatic sprinkler system. In 1950 it reached the market as the Moody Rainmaster, with a promise to liberate homeowners so they could go to the beach for the weekend while their gardens watered themselves. It sold well, and was followed by increasingly sophisticated designs, for which my grandfather was paid royalties until the last of his automatic sprinkler patents expired in the 1970s.

This was a one-in-a-thousand success story; most inventors toil in their workshops and never get to market. But despite at least twenty-six other patents on other devices, he never had another commercial hit. By the time he died in 1988, I estimate he had earned only a few hundred thousand dollars in total royalties. I remember visiting the company that later bought Moody, Hydro-Rain, with him as a child in the 1970s to see his final sprinkler system model being made. They called him Mr. Hauser and were respectful, but it was apparent they didnt know why he was there. Once they had licensed the patents, they then engineered their own sprinkler systems, designed to be manufacturable, economical, and attractive to the buyers eye. They bore no more resemblance to his prototypes than his prototypes did to his earliest tabletop sketches.

This was as it must be; Hydro-Rain was a company making many tens of thousands of units of a product in a competitive market driven by price and marketing. Hauser, on the other hand, was a little old Swiss immigrant with an expiring invention claim who worked out of a converted garage. He didnt belong at the factory, and they didnt need him. I remember that some hippies in a Volkswagen yelled at him for driving too slowly on the highway back from the factory. I was twelve and mortified. If my grandfather was a hero of twentieth-century capitalism, it certainly didnt look that way. He just seemed like a tinkerer, lost in the real world.

![Aliverti Paolo - The Makers manual: [a practical guide to the new industrial revolution]](/uploads/posts/book/177221/thumbs/aliverti-paolo-the-maker-s-manual-a-practical.jpg)