DREAMING

IN PUBLIC

Building the

Occupy Movement

Edited by Amy Schrager Lang

& Daniel Lang/Levitsky

About the Editors

Amy Schrager Lang taught U.S. literature and culture for thirty-five years and remains on the faculty of Syracuse University. She is the author of scholarly books and articles and the co-editor of What Democracy Looks Like: A New Critical Realism for a Post-Seattle World. She co-edits the book series Class : Culture for the University of Michigan Press.

Daniel Lang/Levitsky is a puppeteer, designer, organizer, and agitator based in Brooklyn. Raised radical, grew up queer & gendertreyf; a founding member of the NYC Direct Action Network, Jews Against the Occupation/NYC, and the Aftselokhes Spectacle Committee. Presently a board member of Jews For Racial & Economic Justice, a dancer with the Rude Mechanical Orchestras Tactical Spectacle, and organizer of Just Like That (an affinity group and research collective).

Image Credits

Colin Smith

)

Chris Leary

Ape Lad

Ryan Hayes

(top) Duncan Cumming

(middle) Mikey Walley; (bottom) Laurel Hiebert and Kira Treibergs with artwork by Marley Jarvis

; (bottom) Dave Wilcox

Alexandra Clotfelter

r.black

Dave Loewenstein

(top) Collin Anderson; (middle) Andrew Golledge; (bottom) Zoe Holden

(top & middle) Diane McEachern; (bottom) John Agnello

projection by Mark Read, Denise Vega, Will Etundi, et al.

photo: Julie Abraham

Emma Rosenthal

p325 photo: urban infidel

Other photographs within pieces appear as they did in the online originals. We were unable to contact some photographers and imagemakers, especially those responsible for Occupy Lulz graphics if you are one of them, please contact us at occupy. ; we want to be able to credit you properly.

DREAMING

IN PUBLIC

Building the

Occupy Movement

Edited by Amy Schrager Lang

& Daniel Lang/Levitsky

Dreaming In Public: Building the Occupy Movement

First published in 2012 by

New Internationalist Publications Ltd

55 Rectory Road

Oxford OX4 1BW, UK

newint.org

This book has been compiled by Amy Schrager Lang and Daniel Lang/Levitsky. Copyright over the contributions to the book is held by the individual authors. Their work appears here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license.

All rights to text specifically created for this book are reserved and may not be reproduced without prior permission in writing of the Publisher.

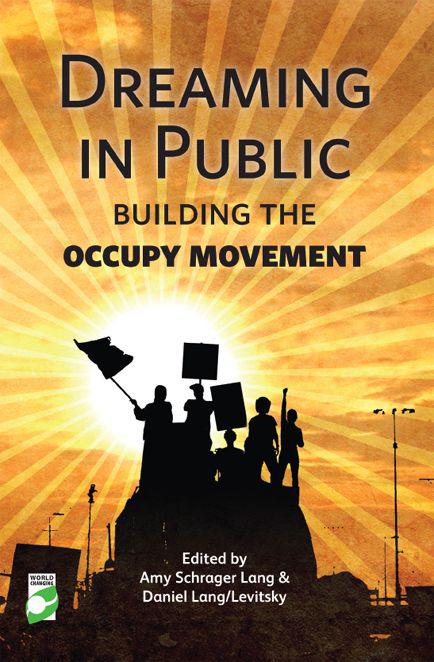

Front cover photograph and design: Tim Simons

Design: Andrew Kokotka and Ian Nixon.

Series editor: Chris Brazier

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-1-78026-085-3

Contents

Staughton Lynd

O ccupy Wall Street took everyone by surprise! That surprise was felt by those who initiated the action as well as by others who, like myself, joined in later.

No doubt like other observant participants, in trying to understand what was happening I used previous experience as a template. The experience that came to my mind was that of the New Left of the early 1960s.

From 1960 to 1967 or 1968, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) professed belief in nonviolence and in what we called participatory democracy. We believed that we are all leaders, and, although we did not use the term, our practice expressed horizontalism. We sought to influence each other by exemplary action rather than by ideological harangue. History, it seemed to us, might come about because Rosa Parks refused to go to the back of a bus, because four young men sat in at a segregated lunch counter, or because David Mitchell refused to be drafted for a war in Vietnam that he considered a war crime.

The Occupy movement exhibits these same characteristics to an astonishing degree. Who would have believed that this structure of feeling could reappear after SNCC and SDS crashed and burned in the late Sixties? It is as if beneath the charred surface of the forest floor all manner of seeds, sprouts, networks of green and growing things, somehow survived and now have reappeared.

Thus SNCC and SDS on the one hand, and Occupy on the other, are alike in their commitment to certain values.

There are particular problems that we in the Sixties failed to resolve and must therefore pass on, in that unhappy state, to protagonists of Occupy.

The first has to do with demands. We had demands in the Sixties: Yes to the right to vote in the Deep South, No to military service in Vietnam. We knew that behind these problems stood an economic system, capitalism. We did not know how to make specific demands that, if acted on, could change capitalism into something better. We passed on this conundrum to those who came after us, who turned out to be Occupy.

We failed in creating an appropriate process of representative government within our Movement as its numbers grew.

We did not know, and proved unable to learn, how to deal with an intransigent minority in the course of Movement decision-making.

This is a formidable collection of unresolved matters!

Sorry about that, brothers and sisters.

But in effect, history has given all of us a second chance. There is excitement in recognizing that the activists in Movements all around the world, gathered, as we have, in downtown public squares (Wenceslas Square in Prague, Tahrir Square in Cairo), are struggling with the same problems.

In the Sixties we supposed that somewhere there was a society that had found solutions to the issues we experienced. If not the Soviet Union, then surely the intrepid guerrillas of Latin America, Algerian women with their battle cry, the Chinese in seeking to pass on the spirit of revolution to a new generation, even the students of Paris, had found the Answers. Painfully, we discovered that was not the case.

We are all in this together.

Staughton Lynd

Longtime US activist, lawyer, historian and author.

A ll of the writing and images we have included in this collection were created and circulated by their authors as part of their active participation in Occupy/Decolonize. Some have been read widely and are understood as key contributions to the movements evolution Manissa McCleave Maharawals So Real It Hurts, for example. Others have reached far fewer people, like the Mortville Declaration of Independence, but are no less significant for that. Still others are part of the ferment of largely anonymous cultural production that has accompanied Occupy photoshopped graphics featuring Lieutenant John Pike (the Pepper Spray Cop) or Occupy Sesame Street images. The selections are strikingly different in tone: earnest, ironic, hilarious, somber, enraged, or all of these by turns. What they share is intensity of feeling; what they do, collectively, is create the movement.

Without these cultural producers, without their work, and without the commitment to social protagonism that animates it, Occupy would not exist, any more than it would without the cooks, trash-haulers, librarians, livestreamers, medics and residents of the encampments. This is no less true of the thousands of other writers, photographers, photoshoppers and so on whose work we have not included. We have chosen these particular works because we feel that they, together, show the scope and the depth of the whole.