CONTENTS

For

Lloyd N. Cutler

and

Sir Michael Howard

Law and strategy, American and Briton:

strongest and wisest when in concert

From A Poem for the End of the Century

When everything was fine

And the notion of sin had vanished

And the earth was ready

In universal peace

To consume and rejoice

Without creeds and utopias,

I, for unknown reasons,

Surrounded by the books

Of prophets and theologians,

Of philosophers, poets,

Searched for an answer,

Scowling, grimacing,

Waking up at night, muttering at dawn.

What oppressed me so much

Was a bit shameful.

Talking of it aloud

Would show neither tact nor prudence.

It might even seem an outrage

Against the health of mankind.

Czeslaw Milosz1

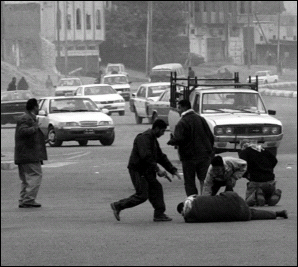

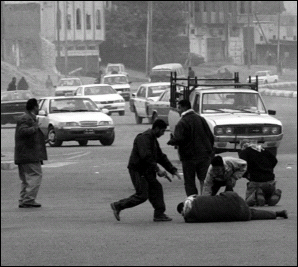

Gunmen execute Iraqi election workers at point-blank range on Haifa Street in Baghdad in an effort to prevent democratic elections to form the new Iraqi state. Photo by an Associated Press stringer, December 19, 2004.

INTRODUCTION

Plagues in the Time of Feast

Oft expectation fails, and most oft there

Where most it promises; and oft it hits

Where hope is coldest, and despair most fits.

William Shakespeare,

Alls Well That Ends Well, 2.1.14547

THE WARS AGAINST TERROR have begun, but it will take some time before the nature and composition of these wars are widely understood. The objective of these wars is not the conquest of territory or the silencing of any particular ideology but rather to secure the environment necessary for states of consent and to make it impossible for our enemies to impose or induce states of terror. The source of these wars is not Islam but rather a fundamental change in the nature of the State and its evolving relationship to the new methods, purposes, and technologies of warfare.1

The wars comprise three different but related efforts at prevention and mitigation: an attempt to preempt attacks by global, networked terrorists; a struggle to prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction; and the worldwide endeavor to protect civilians from natural catastrophes and nonnatural assaults that result in gross diminutions of humane conditions, including human rights. To put it summarily, we are fighting terror, not just terrorists.2

The first two elements of these wars are easy to relate to one another: if terrorists of a certain kind ever achieve their goal of getting nuclear or biological weapons, the risk to the civilian population of the democracies is almost incalculable. What is somewhat harder to see is that these risks are in several important dimensions almost indistinguishable from those imposed by the terror that is the consequence of genocide and ethnic cleansing and also of metropolitan earthquakes, pandemics, tidal waves, and hurricanes. Relieving the suffering and devastation that would be caused by such disasters calls on many of the same resources as the efforts against terrorism and proliferation. This fact will have important implications for the force structures and training of the armed forces of the democracies.

Chiefly, however, this relationship arises because civil trauma is a potential consequence of all three of these elements. The same globalizing factors that multiply the harm latent within each of these three threats also attack the legitimacy of the State. As one thoughtful commentator has concluded:

Transnational terrorism, as represented by al Qaeda and its associated groups, has the potential to undermine the integrity and value of the state itself, destroying the domestic contract of the state by undermining its ability to protect its citizens from direct attack. This form of terrorism is a threat to the sovereignty and the legitimacy of the state itself.3

This observation is true of nuclear and biological threats, and of mass catastrophes. Moreover, these disparate sources of fear and chaos are further related because we must prepare to respond to their consequences when we do not immediately know into which basket of causality they fall. Indeed the most important feature of twenty-first century terrorist attacks may be that we often will not know their authors and must act in conditions of great uncertainty. If a power grid goes down we must respond without knowing whether it was the result of a terrorist attack, a lightning strike, or the act of a precocious California teenager. Acting in the face of uncertainty, with the greater reliance we must place on intelligence and planning, will call for a politics of maturity that will test our leaders, our institutions, and our peoples.

Finally, we must treat the three arenas of the Wars against Terror in relation to one another, because progress in any one often means a worsening situation in the other two. Managing this relationship will be the chief security problem for states of consent, such as the U.S. and Britain, in their struggle against terror.

So this is not a book about the root causes of terrorism unless we want to say that the enhanced vulnerabilities that are manifested in these threats are caused by the same globalizing forces that are changing the constitutional order of the developed states, that have brought the U.S. to a global preeminence, and that threaten that country perhaps most of all. Rather this book is about that change in the constitutional orderfrom nation state to market state and whether that change will result in the triumph of states of consent or states of terror.

TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY TERRORISM

I believe that almost every widely held idea we currently entertain about twenty-first century terrorism and its relationship to the Wars against Terror is wrong and must be thoroughly rethought. In this book I have tried to begin this fundamental rethinking. The looming combination of a global terrorist network, weapons of mass destruction, and the heightening vulnerability of enormous numbers of civilians emphatically requires a basic transformation of the conventional wisdom in international security.

This must be done now for the practical, insistent reason that while at present the United States, the United Kingdom, and our allies are making headway in many sectors4 against al Qaeda in the First Terrorist War, there is no consensus of ideas about the underlying nature of the conflicts against terror. Ultimately, without a realistic and perspicuous understanding of these menacing phenomena on which we can agree, we cannot hope to cope with them successfully. Indeed we may not even be able to avoid falling out among ourselves, with deadly consequences.

Currently, we cling to ways of thinking that brought us success in the past but are ill-suited to our future. I have in mind especially our ideas about terrorism, warfare, and victory (the war aim). Among well-informed persons, a number of dubious propositions about twenty-first century terrorism and the Wars against Terror are widely and tenaciously held. Some of these assumptions are

Next page