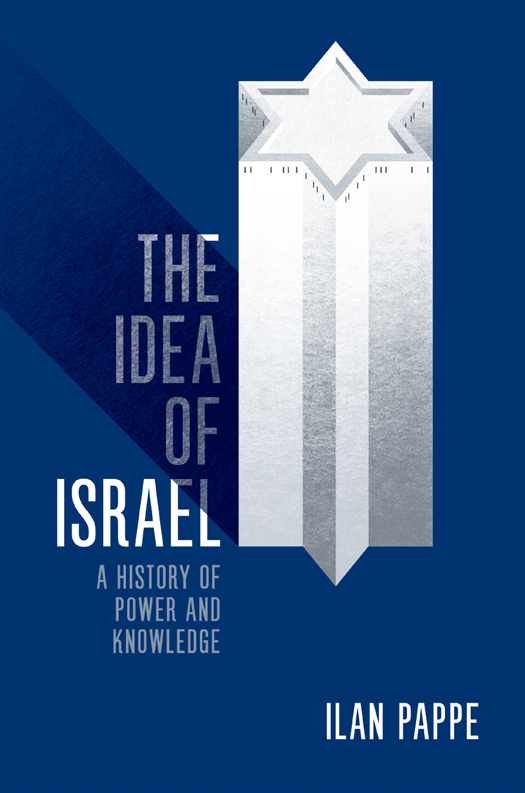

First published by Verso 2014

Ilan Pappe 2014

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-856-3

eISBN: 978-1-78168-247-0 (US)

eISBN: 978-1-78168-545-7 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

INTRODUCTION

Debating the Idea of Israel

A sober and objective consideration of the facts indicates that Zionism, relative to other ideologies, has succeeded in realising most of its objectives. It has done so perhaps more than any other contemporary movement, particularly in light of its unique initial odds, which caused it to be the weakest political movement of all. For all these reasons, it can serve as an example of the success of modernism.

Yosef Gorny, Thoughts on Zionism as a Utopian Ideology

The mutual impact of modern scientific observation and ancient literature as well as archaeology turns the study of the geography of Palestine into the geography of the homeland of the Hebrew people and the study of the culture of the land into the study of Hebrew culture.

Yossef Barslevsky, Did You Know the Land?:

The Galilee and the Northern Valleys

O n a hot night in July 1994, hundreds of people packed a university hall in Tel Aviv to listen to a debate about knowledge and power in Israel. The numbers surprised the organisers. They had planned a small, purely intellectual debate and knowingly chose to hold it during the semi-final game of the World Cup, which was being held in the United States. The hope was that attendance would be limited to the few geeks willing to give up a football night for the sake of a scholarly treat. Nonetheless, students crowded into the undersized hall, and so, on short notice, the event had to be moved to a larger venue. According to one account, seven hundred people attended the debate, which featured one old and one new historian of Israel, as well as one established and one revisionist sociologist. I was the new historian.

The debate itself was anything but the dialogue advertised and ended up as four lectures, punctuated by a certain amount of ill-tempered scuffling. But the public seemed to enjoy themselves as much as the fans cheering the semi-finalists on the other side of the planet.

The question posed was significant: Was the Israeli academy an ideological tool in the hands of Zionism or a bastion of free thought and speech? The vast majority of the audience attended because they leaned towards the former conclusion, doubting the independence of Israeli academics. If approval can be judged by applause, the audience sided by and large with my colleague Shlomo Svirsky and myself, representatives of the new history and sociology of Israel, and were less impressed by Anita Shapira and the late Moshe Lissak of the old guard. Most, however, would not walk the extra mile that such a position demanded of them. And yet that event contributed to the excitement of a historic moment when Israelis doubted the moral validity of the idea of Israel and were allowed, for a short while, to question it, both inside and outside the ivory towers of the universities.

The most memorable remark that evening came from Moshe Lissak, the doyen of traditional Israeli sociology and a winner of the prestigious Israel Prize. Of the story of Israel, he said, I accept that there are two narratives, but ours has been proven scientifically to be the right one. That remark, and my fond memories of that event and of the period as a whole unique in the history of power and knowledge inspired me to write this present book. It is a book on Israel as an idea, and it evolved from that short-lived and abortive attempt to challenge it from within.

Every book on Israel attempts to dissect a complex and ambiguous reality. Yet however one chooses to describe, analyse and present Israel, the result will always be both subjective and limited. Nevertheless, the subjectivity and relativity of any representation do not invalidate moral and ethical discussion about that representation. In fact, from the vantage point of the early twenty-first century, the moral and ethical dimensions of such a debate are no less important than questions of substance, facts and evidence. As in the debate in Tel Aviv, versions of reality in Israel are numerous and contradictory, and rarely do they share any consensual ground.

But it must be stressed that they are not just versions of an intellectual debate. They relate directly to issues of life and death, and therefore any attempt to conduct such a conversation in a neutral, objective, purely scientific way is doomed to fail. Israel, or rather the idea of Israel, symbolises for an ever-growing number of people oppression, dispossession, colonisation and ethnic cleansing, while, on the other hand, an ever-diminishing number of people string the same ideas and events into a story of redemption, heroism and historical justice. Along the continuum between these two extremes lie innumerable gradations of strongly held opinion.

In this book, I will argue that these opposing versions are not about Israel as such, but rather about the idea of Israel. Obviously, Israel itself is not merely an idea. It is first and foremost a state a living organism that has existed for more than sixty years. Denying its existence is impossible and unrealistic. However, evaluating it ethically, morally, and politically is not only possible but also, at present, urgent as never before.

Indeed, Israel is one of a few states considered by many to be at best morally suspect or at worst illegitimate. What is challenged, with varying degrees of conviction and determination, is not the state itself but rather the idea of the state. Some may say they challenge the ideology of the state; meanwhile, some Israeli Jews may tell you they fight for the survival of the ideal of the state. The optimal term through which to examine the two sides of the argument, however, is idea.

Israel was one such transformative idea. To challenge it as such is to challenge the entire narrative of the West as the driving global force of human progress and enlightenment. In the eyes of Yosef Gorny, quoted above, Zionism is one of the few modernisation projects that was successfully implemented, if not the only one, despite the array of counterforces that rejected enlightenment and tried to arrest human progress. This is why he chose to call it not an idea, as would most Zionist scholars, but a utopian ideology that had been translated into a fact. In short, he saw it as an idea successfully fulfilled.

But this is not a book that inquires why the idea of Israel is so negatively perceived by so many people, or why Israeli Jews and their supporters are so adamant about the moral validity of their view and so ready to brand any critique as a display of anti-Semitism. Here I am concerned with those Israelis who share the critical view and harbour doubts about the idea of their state. Doubting the idea of Israel constitutes a serious predicament for an Israeli Jew, as it goes beyond criticism of a given policy of this or that government. It means one is troubled by the very essence of the idea.