INTRODUCTION

I began an earlier book with the sentence The First World War was a cruel and unnecessary war. The American Civil War, with which it stands comparison, was also certainly cruel, both in the suffering it inflicted on the participants and the anguish it caused to the bereaved at home. But it was not unnecessary. By 1861 the division caused by slavery, most of all among other points of division between North and South, was so acute that it could have been resolved only by some profound shift of energy, certainly from belief in slavery as the only means by which Americas colour problem could be contained, probably by a permanent separation between the slave states and their sympathisers and the rest of the country, and possibly, given the ruptions such a separation would have entailed, by war. That did not mean, however, that war was unavoidable. All sorts of political and social variables might have led to a peaceful resolution. Had the North had an established instead of a newly elected president, and a president whose anti-slavery views were less provocative to the South; had the South had leaders, particularly a potential national leader, as capable and eloquent as Lincoln; had both sections, but particularly the South, been less affected by the amateur militarism of volunteer regiments and rifle clubs which swept the Anglo-Saxon world on both sides of the Atlantic in mid-century; had industrialisation not so strongly fed the Norths confidence that it could face down Southern bellicosity; had Europes appetite for Southern cotton not persuaded so many planters and producers below the Mason-Dixon line that they had the means to dictate the terms of a separatist diplomacy to the world; had so many had nots not clustered in the mentality of both North and South, then simple and scant regard for peace and its maintenance might have overcome the clamour of marching crowds and recruiting rallies and pointed the great republic through the turmoil of war fever to the normality of calm and compromise. Americans were great compromisers. Half a dozen major compromises had averted the crisis of division already during the nineteenth century. Indeed, a tacit resort to compromise had led the whole country to adopt compromise as the guiding principle of relations with the old colonial overlords at the beginning of the century and to forswear conflict with Britain, after the aberration of the War of 1812, in perpetuity. Unfortunately, Americans were also people of principle. They had embodied principle in the guiding preambles to their magnificent governing documents, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, and, when aroused, Americans resorted to principle as their guiding light out of trouble. Even more unfortunately, the main points of difference between North and South in 1861 could be represented as principles; the indivisibility of the republic and its sovereign power and states rights both had to do with the passions of the republics golden age and could be invoked again when the republics survival was under threat. They had been invoked, iterated, and reiterated throughout the political quarrels of the centurys earlier decades by protagonists of great sincerity and eloquence, Henry Clay and John Calhoun. It was finally unfortunate that America produced opinion leaders of formidable persuasiveness. It was the Souths ill fortune that, having dominated the debate in the first half of the century, at precisely the point when the issue of principle ceased to be a contest of words and threatened to become a call to action, the North had produced a leader who spoke better and more forcefully than any of the Souths current champions.

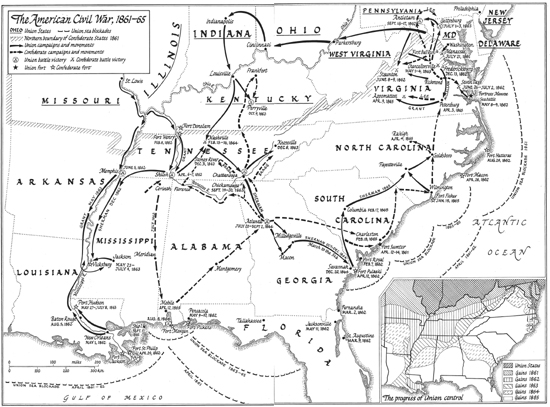

War must have been very close beneath the surface of debate in 1861, for scarcely had the South moved to the level of organisation for secession than it was appointing not only its own Confederate president but also a secretary for war, as well as secretaries of state and of the treasury and the interior. Scarcely had President Lincoln assumed office before he was embodying the militias of the Northern states for federal service and calling for volunteers in tens of thousands. In only a few weeks one of the most peaceable polities in the civilised world was bristling with, if not armed men, then men demanding arms and marching and drilling in the manual of arms. It would take time for the arms to appear. The delay would not, however, abate the turmoil, for the challenge to the republics integrity and authority had aroused profound popular passions. In the Old World, it had become, through struggles for national liberation, as much in the Spanish-speaking part of the continent as in the English-speaking half, the concern of populations. The Americas of 1861, North and South alike, had decided by unspoken consensus that the issues of principle the quarrel provoked by the election of Abraham Lincoln was grave enough to be fought over. The decision was to invest the coming conflict with a grim purpose. It would become a war of peoples, and those of each side, who had hitherto considered themselves one, would henceforth begin to perceive their differences and to consider their differences more important than the values that, since 1781, they had accepted as permanent and binding. The coming war would thus be a civil war, and it was quickly so called and recognised to be. In the meantime, however, the leaders of North and South turned to consider what form the war should take if war overtook their peoples. The matter, for the South, was simple. It would defend its borders and repel any invaders who appeared. For the North, things were not so simple. Any war would be a rebellion, a defiance of its authority which had to be defeated; but how and, more crucially, where should defeat be inflicted? The South formed half the national territory, an enormous area that touched the Norths organised regions at only a few widely separated points. There was contact between the South and the Norths region of great cities in the Atlantic coast corridor of Maryland and Pennsylvania, a region amply supplied with railroads; there were some tenuous connections between North and South in the Mississippi Valley, where there were extensive riverine links, but a dearth of cities and population. As a result, when war broke out in April 1861, it began in a haphazard, unplanned, and largely undirected form, the embryo armies falling upon each other as and when found. The first encounters would occur in what would become the state of West Virginia, minor engagements on what the correspondent of the London