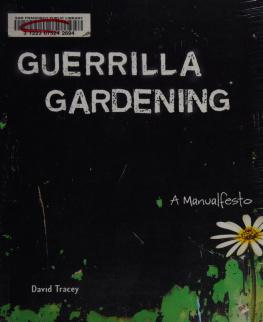

RICHARD REYNOLDS founded GuerrillaGardening.org in 2004. He was born in 1977 and grew up in Devon, England. He has qualifications in Geography from Oxford University and in horticulture from the Royal Horticultural Society.

First published in 2008

This electronic edition published in 2014 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright 2008 by Richard Reynolds

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square

London WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

Bloomsbury is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 978-1-4088-5639-0

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters here.

To my mischievous Mother 008

Contents

Five years ago I became a guerrilla gardener. I stepped out into the world to cultivate land wherever I liked. The mission was to fight the miserable public flowerbeds around my neighbourhood.

Until then I had always lived, more or less, on the right side of the law. I had recently moved to a high-rise flat on a bleak roundabout in south London an area notorious for its labyrinth of pedestrian underpasses, garish pink shopping centre and traffic volumes to rival Britains busiest motorways. It is the kind of environment that drives people to crime. My crime was gardening on public land without permission and battling whatever was in the way.

Even when one has permission, cultivating a garden is always a fight. We cut back one plant to allow another one to flourish; we scatter seeds, but we rip up weeds and snatch away flowers and fruit before their seed has dispersed. Our gardens are scenes of savage destruction. Animals uproot, frosts cripple, winds topple, rains flood. The guerrilla gardener shares this constant battle with nature with other gardeners. But we have other enemies and ambitions. This handbook has been compiled from my experience of guerrilla gardening and that of guerrilla gardeners around the world. Radical and reticent, active and retired, successes and failures they have all shaped these pages. I have also drawn on the documented advice of conventional guerrillas, whose analysis of strategies and tactics can be applicable to our fight. The debate and instruction goes well beyond gardening. To succeed a guerrilla gardener needs to know more. Do not be daunted: read on.

Richard Reynolds

Elephant & Castle, January 2009

You will see that most names in this book are followed by numbers. These are their troop numbers, assigned to volunteers when they enlist at GuerrillaGardening.org. Surnames have been omitted because some guerrilla gardeners prefer to remain anonymous. Only guerrilla gardeners who are no longer alive are referred to by their full name.

Part One:

The Movement

Picture a garden.

Step into it. Stroll around.

What do you see? Perhaps a riot of tumbling terraces, topiary and pergolas, a cheerful blast of a blooming border or an explosive vegetable patch. Or maybe you are just reminded of the muddy lawn and cracked concrete patio in your garden that resembles a war zone. Whatever garden you are now imagining, it is likely that to one side of it stands a house.

You are picturing a garden as most people see one as an extension of a home, a landscaped setting to live in, a private space

Over the hill from that garden is another patch of cultivated private space. This one is so big we call it a market garden or farm, and while the owner there may grow strawberries (Fragaria x ananassa) instead of red roses (Rosa Super Star) the basic structure is the same: a home and a private garden.

A few readers will have pictured a flowerbed in front of an apartment block or perhaps a lush and leafy park. These are different because the land is publicly accessible. The owner (or whoever is responsible for it) has cultivated the space perhaps with a bed of primroses (Primula polyanthus) or an avenue of lime trees (Tilia x europaea) for shared enjoyment. Yet there are limits to this enjoyment. You may survey the scene and sniff the flowers but, as the saying goes, take nothing but photographs, leave nothing but footprints and kill nothing but time, because this is not your garden to tend.

The received opinion is that if you want to be a gardener then you must do so in your own garden or else find a way to be employed or permitted to garden someone elses land.

But some people have a different definition of gardening. I am one of them. I do not wait for permission to become a gardener but dig wherever I see horticultural potential. I do not just tend existing gardens but create them from neglected space. I, and thousands of people like me, step out from home to garden land we do not own. We see opportunities all around us. Vacant lots flourish as urban oases, roadside verges dazzle with flowers and crops are harvested from land that was assumed to be fruitless. In all their forms these have become known as guerrilla gardens. The attacks are happening all around us and on every scale from surreptitious solo missions to spectacular horticultural campaigns by organized and politically charged cells. This is guerrilla gardening:

THE ILLICIT CULTIVATION

OF SOMEONE ELSES LAND.

The battle is gathering pace. Most people own no land. Most of us live in cities and have no garden of our own. We demand more from this planet than it has the space and resources to offer. Guerrilla gardening is a battle for resources, a battle against scarcity of land, environmental abuse and wasted opportunities. It is also a fight for freedom of expression and for community cohesion. It is a battle in which bullets are replaced with flowers (most of the time).

1.1 Little War

Guerrilla is a Spanish word meaning little war one in which informal combatants make sporadic attacks rather than fighting in great blocks of traditional forces. The first little war of this kind was in 516 BC when the Scythians fought against the invading Persian army of King Darius with nocturnal raids on its supply lines rather than with traditional open field combat.

The g-word was first used to describe the military response to Napoleon Bonapartes invasion of Spain in 1808. For six years, irregular bands of Spanish fighters attacked the huge occupying imperial French army with little ambushes and civilian agitation. Ordinary men, not trained soldiers, proudly took up arms to defend their country from the invaders and called themselves