THE LAST EMPIRE

Copyright 2014 by Serhii Plokhy

Published by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 8104145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Book design by Cynthia Young

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-0-465-06199-0 (e-book)

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To the children of empires who set themselves free

Contents

I T WAS A CHRISTMAS GIFT that few expected to receive. Against the dark evening sky, over the heads of tourists on Red Square in Moscow, above the rifles of the honor guard marching toward Lenins mausoleum, and behind the brick walls of the Kremlin, the red banner of the Soviet Union was run down the flagpole of the Senate Building, the seat of the Soviet government and until recently the symbol of world communism. Tens of millions of television viewers all around the world who watched the scene on Christmas Day 1991 could hardly believe their eyes. On the same day, CNN presented a live broadcast of the resignation speech of the first and last Soviet president, Mikhail Gorbachev. The Soviet Union was no more.

What had just happened? The first to give an answer to that question was the president of the United States, George H. W. Bush. On the evening of December 25, soon after CNN and other networks broadcast Gorbachevs speech and the image of the red banner being lowered at the Kremlin, Bush went on television to explain to his compatriots the meaning of the picture they had seen, the news they had heard, and the gift they had received. He interpreted Mikhail Gorbachevs resignation and the lowering of the Soviet flag as a victory in the war that America had fought against communism for more than forty years. Furthermore, Bush associated the collapse of communism with the end of the Cold War and congratulated the American people on the victory of their values. He used the word victory three times in three consecutive sentences. A few weeks later, in his State of the Union address, Bush referred to the implosion of the Soviet Union in a year that had seen changes of almost biblical proportions, declared

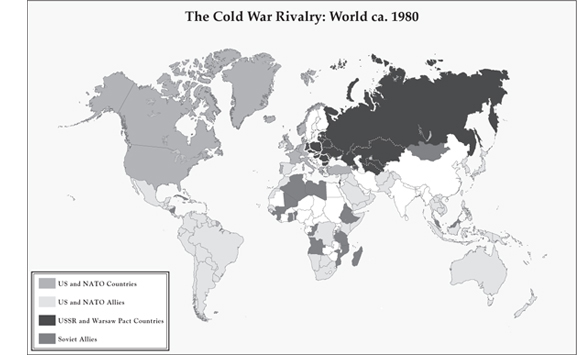

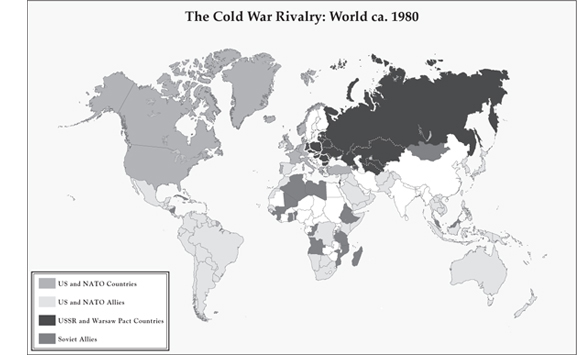

For more than forty years, the United States and the Soviet Union had indeed been locked in a global struggle that by sheer chance did not end in a nuclear holocaust. Generations of Americans were born into a world that seemed permanently divided into two warring camps, one symbolized by the red banner atop the Kremlin and the other by the Stars and Stripes over the Capitol. Those who went to school in the 1950s still remembered the nuclear alarm drills and the advice to hide under their desks in case of a nuclear explosion. Hundreds of thousands of Americans fought and tens of thousands died in wars that were supposed to stop the advance of communism, first in the mountains of Korea and then in the jungles of Vietnam. Generations of intellectuals were divided over the issue of whether Alger Hiss spied for the Soviets, and Hollywood remained traumatized for decades by the witch hunt for communists unleashed by Senator Joseph McCarthy. Only a few years before the Soviet collapse, the streets of New York and other major American cities were rocked by demonstrations staged by proponents of nuclear disarmament that divided fathers and sons, pitting the young political activist Ron Reagan against his father, President Ronald Reagan. Americans and their Western allies fought numerous battles at home and abroad in a war that seemed to have no end. Now an adversary armed to the teeth, never having lost a single battle, lowered its flag and disintegrated into a dozen smaller states without so much as a shot being fired.

There was good reason to celebrate, but there was also something confusing, if not disturbing, about the presidents readiness to claim victory in the Cold War on the day when Mikhail Gorbachev, Bushs and Ronald Reagans principal ally in ending that war, submitted his resignation. Gorbachevs action put a symbolic if not legal end to the USSR (it had been formally dissolved by its constituent members four days earlier, on December 21), but the Cold War was never about the dismemberment of the USSR. Besides, President Bushs speech to the nation on December 25, 1991, and his State of the Union address in January 1992 contradicted the administrations earlier

Bushs Christmas address was a major departure from the way in which the president himself and the members of his administration had treated their erstwhile Soviet partner and assessed their ability to affect developments in the Soviet Union. Whereas Bush and his national security adviser, General Brent Scowcroft, had insisted publicly for most of 1991 that their influence was limited, they were now suddenly taking credit for the most dramatic development in Soviet domestic politics. This new interpretation, born in the midst of Bushs reelection campaign, gave rise to an influential, if not dominant, public narrative of the end of the Cold War and the emergence of the United States as the sole world superpower. That largely mythical narrative closely linked the end of the Cold War with the collapse of communism and the disintegration of the Soviet Union. More important, it treated those developments as direct outcomes of US policies and, indeed, as major American victories.

This book challenges the triumphalist interpretation of the Soviet collapse as an American victory in the Cold War. It does so in part on the basis of recently declassified documents from the George Bush Presidential Library, including memoranda from his advisers and formerly secret transcripts of the presidents telephone conversations with world leaders. These newly available documents show with unprecedented clarity that the president himself and many of his White House advisers did much to prolong the life of the Soviet Union, worried about the rise of the future Russian president Boris Yeltsin and the drives for independence by leaders of other Soviet republics, and, once the Soviet Union was gone, wanted Russia to become the sole owner of the Soviet nuclear arsenals and maintain its influence in the post-Soviet space, especially in the Central Asian republics.

Why did the leadership of a country allegedly locked in combat with a Cold War adversary adopt such a policy? The White House documents, combined with other types of sources, provide answers to this and many other relevant questions posed in this book. They show how Cold Warera political rhetoric clashed with realpolitik as the White House tried to save Gorbachev, whom it regarded as its main partner on the world stage. The White House was prepared to tolerate the continued existence of the Communist Party and the Soviet empire in order to achieve that goal. Its main concern was not victory in the Cold War, which was already effectively over, but the possibility of civil war in the Soviet Union. That would have threatened to turn the former tsarist empire into a Yugoslavia with nukes, to use a term coined by newspaper reporters at the time. The nuclear age had changed the nature of great-power rivalry and the definition of victory and defeat, but not the rhetoric of the warriors ethos or the thinking of the masses. The Bush administration had to square the circle by reconciling the language and thinking of the Cold War era with the geopolitical realities of its immediate aftermath. It did its best in that regard, but its actions far outshone its inconsistent rhetoric.

Next page