THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2014 by Sven Beckert

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto,

Penguin Random House companies.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Beckert, Sven.

Empire of cotton : a global history / Sven Beckert.First edition.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-375-41414-5 (hardcover)ISBN 978-0-385-35325-0 (eBook) 1. Cotton textile industryHistory. 2. Cotton tradeHistory. 3. Cotton plantation workersHistory. 4. SlaveryEconomic aspects. 5. Slaves. 6. Textile workers. 7. CapitalismHistory. 8. LaborHistory. I. Title.

HD9870.5.B43 2014

338.4767721dc23 2014009320

Maps by Mapping Specialists

Jacket images: (top to bottom) Spinning Mill at Dornach by Jean Mieg. Muse Historique de Mulhouse; Cotton-making, Dutch Antilles, East Indies by Paolo Fumagalli. Private Collection. The Stapleton Collection / The Bridgeman Art Library; A Loom British Library Board. All Rights Reserved / The Bridgeman Art Library

Jacket design by Eric White

First Edition

v3.1

For Lisa

Contents

Chapter 1

The Rise of a Global Commodity

Chapter 2

Building War Capitalism

Chapter 3

The Wages of War Capitalism

Chapter 4

Capturing Labor, Conquering Land

Chapter 5

Slavery Takes Command

Chapter 6

Industrial Capitalism Takes Wing

Chapter 7

Mobilizing Industrial Labor

Chapter 8

Making Cotton Global

Chapter 9

A War Reverberates Around the World

Chapter 10

Global Reconstruction

Chapter 11

Destructions

Chapter 12

The New Cotton Imperialism

Chapter 13

The Return of the Global South

Chapter 14

The Weave and the Weft: An Epilogue

Introduction

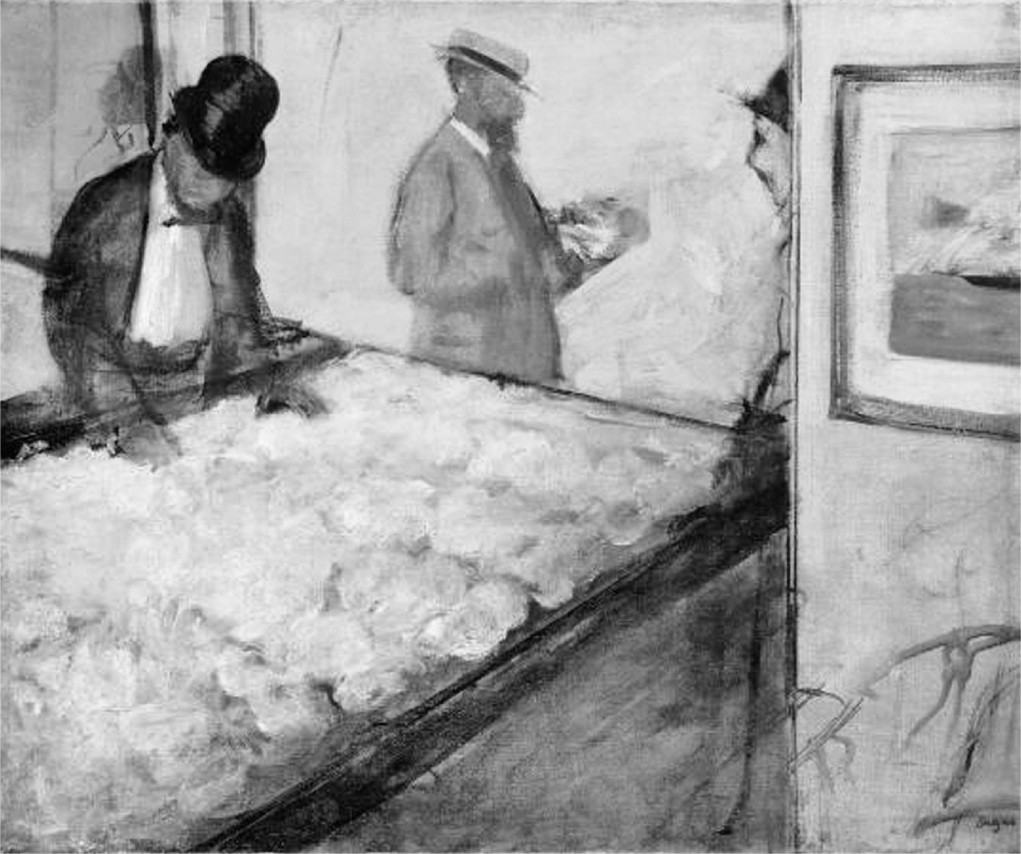

Edgar Degas views the empire of cotton:

In late January 1860, the members of the Manchester Chamber of Commerce assembled in that citys town hall for their annual meeting. Prominent among the sixty-eight men who gathered in the center of what was then the most industrialized city in the world were cotton merchants and manufacturers. In the previous eighty years, these men had transformed the surrounding countryside into the hub of something never before seena global web of agriculture, commerce, and industrial production. Merchants bought raw cotton from around the world and took it to British factories, home to two-thirds of the worlds cotton spindles. An army of workers spun that cotton into thread and wove it into finished fabrics; then dealers sent those wares out to the worlds markets.

The assembled gentlemen were in a celebratory mood. President

These self-satisfied cotton manufacturers and merchants had reason to be smug: They stood at the center of a world-spanning empirethe empire of cotton. They ruled over factories in which tens of thousands of workers operated huge spinning machines and noisy power looms. They acquired cotton from the slave plantations of the Americas and sold the products of their mills to markets in the most distant corners of the world. The cotton men debated the affairs of the world with surprising nonchalance, even though their own occupations were almost banalmaking and hawking cotton thread and cloth. They owned noisy, dirty, crowded, and decidedly unrefined factories; they lived in cities black with soot from coal-fueled steam engines; they breathed the stench of human sweat and human waste. They ran an empire, but hardly seemed like emperors.

Only a hundred years earlier, the ancestors of these cotton men would have laughed at the thought of a cotton empire. Cotton was grown in small batches and worked up by the hearth; the cotton industry played a marginal role at best in the United Kingdom. To be sure, some Europeans knew of beautiful Indian muslins, chintzes, and calicoes, what the French called indiennes, arriving in the ports of London, Barcelona, Le Havre, Hamburg, and Trieste. Women and men in the European countryside spun and wove cottons, modest competitors to the finery of the East. In the Americas, in Africa, and especially in Asia, people sowed cotton among their yam, corn, and jowar. They spun the fiber and wove it into the fabrics that their households needed or their rulers demanded. As they had for centuries, even millennia, people in Dhaka, Kano, and Teotihuacn, among many other places, made cotton cloth and applied beautiful colors to it. Some of these fabrics were traded globally. Some were of such extraordinary fineness that contemporaries called them woven wind.

Instead of women on low stools spinning on small wooden wheels in their cottages, or using a distaff and spinning bowl in front of their hut, in 1860 millions of mechanical spindlespowered by steam engines and operated by wage workers, many of them childrenturned for up to fourteen hours a day, producing millions of pounds of yarn. Instead of householders growing cotton and turning it into homespun thread and hand-loomed cloth, millions of slaves labored on plantations in the Americas, thousands of miles away from the hungry factories they supplied, factories that in turn were thousands of miles removed from eventual consumers of the cloth. Instead of caravans carrying West African cloth across the Sahara on camels, steamships plied the worlds oceans, loaded with cotton from the American South or with British-made cotton fabrics. By 1860, the cotton capitalists who assembled to celebrate their accomplishments took as a fact of nature historys first globally integrated cotton manufacturing complex, even though the world they had helped create was of very recent vintage.

But in 1860, the future was nearly as unimaginable as the past. Manufacturers and merchants alike would have scoffed if told how radically the world of cotton would change in the following century. By 1960, most raw cotton came again from The empire of cotton, at least the part dominated by Europe, had come crashing down.

This book is the story of the rise and fall of the European-dominated empire of cotton. But because of the centrality of cotton, its story is also the story of the making and remaking of global capitalism and with it of the modern world. Foregrounding a global scale of analysis we will learn how, in a remarkably brief period, enterprising entrepreneurs and powerful statesmen in Europe recast the worlds most significant manufacturing industry by combining imperial expansion and slave labor with new machines and wage workers. The very particular organization of trade, production, and consumption they created exploded the disparate worlds of cotton that had existed for millennia. They animated cotton, invested it with world-changing energy, and then used it as a lever to transform the world. Capturing the biological bounty of an ancient plant, and the skills and huge markets of an old industry in Asia, Africa, and the Americas, European entrepreneurs and statesmen built an empire of cotton of tremendous scope and energy. Ironically, their shocking success also awakened the very forces that eventually would marginalize them within the empire they had created.